While the global fight against HIV shows many signs of progress, there are still entire populations without sufficient access to necessary medical care. Canada's Aboriginal community is one of them. When Pulitzer Center grantee Daniella Zalcman went to learn more about these problems, she discovered another story: the devastating results of the Canadian government network of Indian Residential Schools meant to assimilate young indigenous students into Canadian culture.

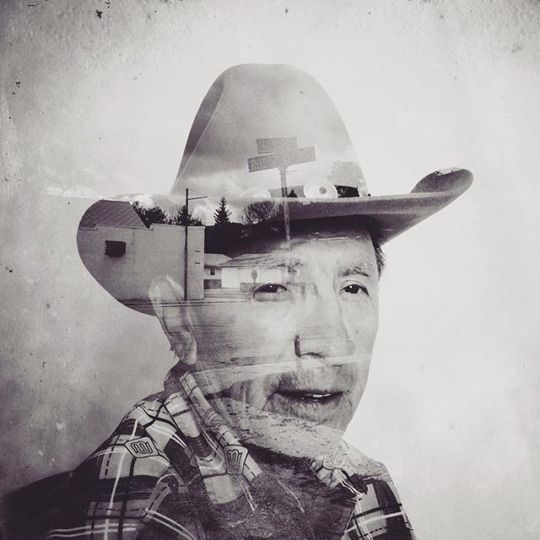

Zalcman spent three weeks in Saskatchewan in the summer of 2015, telling the stories of those who survived one of the darkest chapters in Canadian history. She used double exposure photography, overlaying portraits of survivors with images significant to their experiences.

After CBC/Radio Canada interviewed Grant Severeight, one of the survivors Zalcman photographed, media outlets across Canada picked up her haunting photography and spoke with her about her work.

Coverage of Zalcman and her project appeared in: The StarPhoenix, The Star, Panow, The Spec, City News, 680 News, and News Radio Station CJME.

Photographs from Zalcman's project "Signs of Identity in Canada's First Nation" also have been featured on The New Yorker Instagram and Fishbowl NY.

Zalcman used double exposure photography in her first project with the Pulitzer Center as well, "Kuchus in Uganda," to protect the identities of the people she interviewed. The result was an intimate focus on the LGBT-rights movement and role of religion in Uganda.