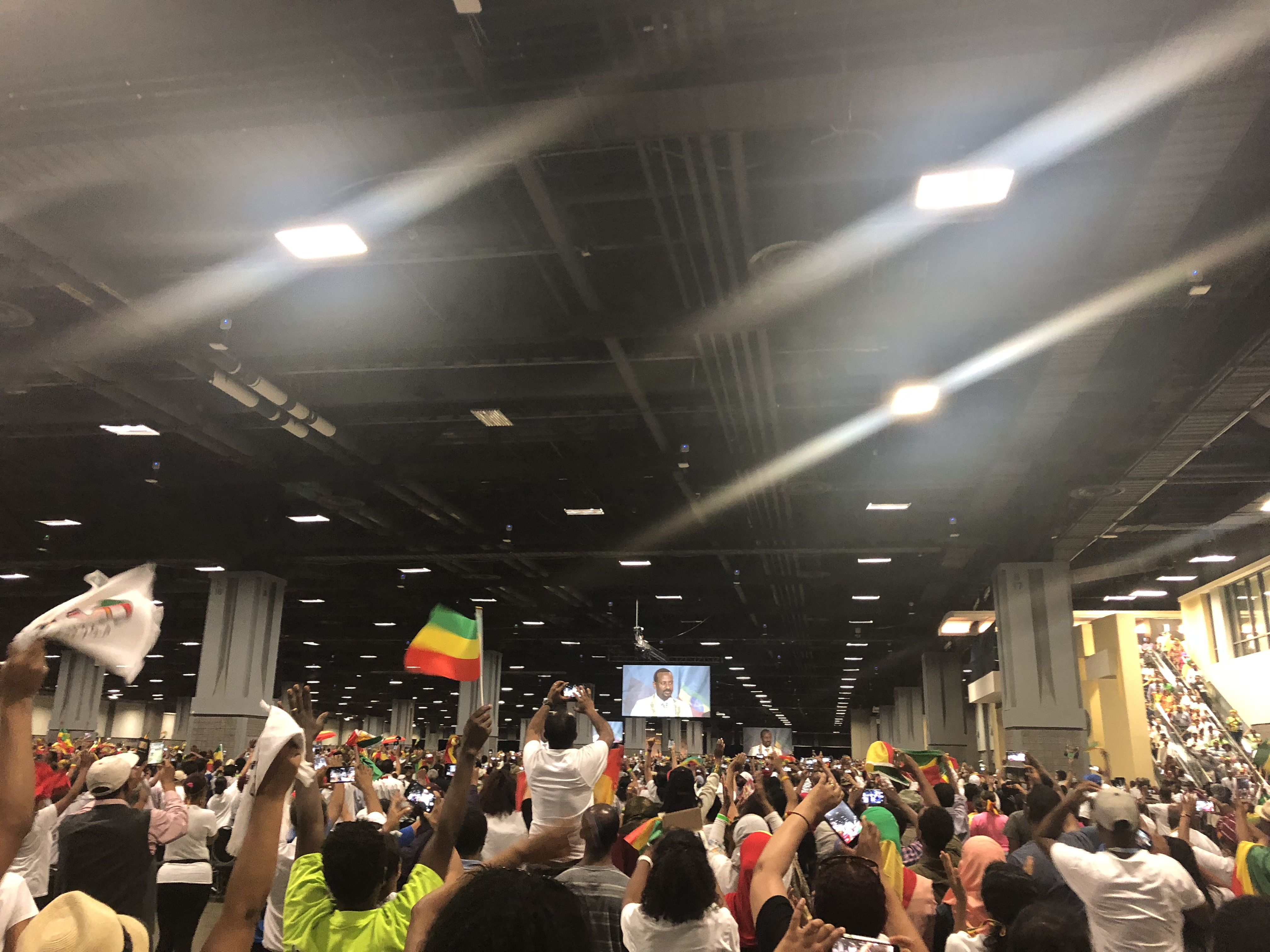

Anyone near 9th and M Streets NW in downtown Washington, D.C., on one hot Saturday this summer would have seen steady streams of people in the vibrant green, red, and yellow of the Ethiopian flag making their way to the Walter E. Washington Convention Center. There they would join thousands of other Ethiopians who had flooded into the city from across the country to hear their recently elected prime minister Abiy Ahmed speak that afternoon.

Entrepreneurial young Ethiopian-Americans went up and down the line selling pins and T-shirts emblazoned with Abiy’s face. At times someone in the crowd would start a spontaneous chant of “Abiy” and people would enthusiastically chime in.

Hours later, when some realized that not everyone in the 35,000-strong crowd would make it inside, the line broke down and there was a rush to the door as the crowd tried to force its way inside.

Abiy is the first Ethiopian prime minister to come to the United States expressly to develop his ties to the diaspora community, largely because he is the first who would have been met with support rather than protest. As recently as January, headlines about Ethiopia predicted its imminent collapse.

Now, just a few months after those grim predictions, Ethiopia is suddenly brimming over with hope. During the first few months in office, Abiy has led this transformation. He has freed thousands of political prisoners, led a detente with Eritrea, invited exiled opposition parties back into the country, and won the support of over 90 percent of Ethiopia.

On July 28, he came to D.C.—home to the greatest number of Ethiopians anywhere outside Africa—to make the diaspora a part of his reforms.

Turning Hope into Action

When Elias Woldu heard that the prime minister was coming to the United States, he volunteered to be one of the 500 volunteers who organized the event in Washington, D.C.

When he visited the United States as a young student over 30 years ago, he never expected that he was moving away from his home forever. “I wanted to go back all the time,” he remembers, but as the situation in Ethiopia descended further into chaos, he knew that he had to make his life here. As years passed, he says that “there was hope that something better could [happen] in the country, but I never expected, in my lifetime, to see it."

The constant stream of bad news coming from Ethiopia made people in the diaspora believe that hoping for reform in the near future was foolish. Then Abiy gave them hope.

Now, many of them have great ambitions for Ethiopia. One man, Mezmure Ori, noted that Ethiopia has one of the youngest populations in the world and abundant natural resources, such as the oil deposits it has yet to tap. If his country is able to develop its economy—which Abiy is determined to do—he believes “we will be a good example for other African countries, and become one of the strong countries in Africa.” He thinks Ethiopia could be the next South Korea.

People at the rally were eager to be a part of their country’s development. And that’s in part why Abiy was here: he has asked that Ethiopians outside the country donate one dollar a day to the Diaspora Trust Fund to help make his $12.6 billion budget—aimed heavily at economic initiatives—a reality. Everyone I asked said they had either already pledged to donate or were planning to any day.

A Second Moses?

Although hope was in the air, there was also an undercurrent of apprehension. As one woman at the rally, Agena Ghebri, said “I’m happy, (but) in the meantime fearful just because there is a part of the last administration trying to diminish the moment we are having right now.”

She was referring to the factions of the ruling coalition, the EPRDF, which held onto power for the last 27 years by torturing, arresting, and killing anyone who opposed it. Abiy is part of the EPRDF, but he is reforming the country and represents a shift in power—earning him plenty of enemies. Just last June, there was an attempt on his life.

On July 28, the day of the Washington, D.C., gathering, there were police officers surrounding the area, metal detectors at every entrance to the Convention Center, and even a ban on bringing in the small sticks attached to the flags people had brought. The fear was palpable, and without Abiy, the change he had begun could suddenly collapse.

Woldu was not afraid for Abiy because, as he explained, “I think God is using him, and I think nothing will happen to him.”

Woldu is not alone in crediting God with Abiy and his sudden reforms. Many see Abiy as a second Moses sent by God to save Ethiopia. Abiy, who rose up through the ranks of the EPRDF, was not a likely vessel for reform.

As Sisay Kuta, an Ethiopian man living in D.C., explained, Moses also spent years by the side of those who oppressed his people, but “he saw what happened to his people, and then he was bleeding inside. And (Abiy) was the same.”

From Skepticism to Visions of Going Home

Abiy’s reforms came so unexpectedly that it is understandable that see his rise as miraculous. Previous politicians used ethnicity and religion to divide the Ethiopian people, but Abiy keeps stressing national unity, as he did on July 28. Although his words have yet to truly overcome the deepset divisions among Ethiopians, at least the overwhelming majority of Ethiopians both at home and abroad are united in their support of him.

As Soleyana Gebremichael, an Ethiopian human rights activist based in D.C., pointed out, winning the support of the diaspora community is a major political accomplishment. Historically, the diaspora has always been the source of nearly all protest against the Ethiopian government. Without the safety of distance, activists faced torture and imprisonment.

Now, for the first time, the diaspora supports the leader of Ethiopia. On July 28, Abiy even embraced Tamagne Beyene, who has been one of the most outspoken critics of the EPRDF regime over the course of the last 27 years, on stage at the Convention Center. By winning the support of the leaders of the diaspora, Abiy is politically neutralizing the most vocal and active opposition the Ethiopian government has ever had.

Anyone at the July 28 rally would have been struck by what a broad range of people in the diaspora Abiy has been able to win over.

Eritreans had come to support Abiy because he put an end to the decades of conflict that divided the two countries after their bloody war in the 1990s. For decades there had been no communication between Eritrea and Ethiopia; families who were separated by the border couldn’t even visit each other. Even in D.C., as Kuta explained, “the people from Ethiopia don’t go to Eritrean restaurant, the Eritrean people don’t come to Ethiopian restaurants.” But on July 28, they celebrated side by side.

Ethiopians who had spent years protesting the EPRDF, like Malaki who had come to the U.S. five years ago as an asylee, came to support Abiy. Malaki [who did not provide his last name] is a member of an opposition party, so the EPRDF would have imprisoned him if he hadn’t escaped.

At first Malaki was skeptical of Abiy because, as he explained, “[Abiy] came from the same party and I still have some doubts, but in the first hundred days I see a lot of changes.” Now that he has seen that Abiy is serious about reform, he fully supports him.

Like Malaki, Gebremichael thought that she would never be able to go home again because she has spent years working to uncover the abuses of the EPRDF. She started the Ethiopia Human Rights Project, a nonprofit based in Washington, D.C., that has gathered information on the cases of the political prisoners and journalists imprisoned without any due process.

As an activist, Gebremichael describes Abiy’s change as “disorienting.” He is releasing the last of Ethiopia’s political prisoners, so her day-to-day work is largely unnecessary now. The big questions that have always been on the horizon about what a reformed Ethiopia will look like are now at hand. The speed of Abiy’s reforms has contributed to high hopes and popularity, but Gebremichael fears that her country is poorly prepared to address those big questions and lacks the stability to make long-lasting reform a certainty.

On a personal level, Abiy has changed her life. Gebremichael never thought she would go home again, and now she will this November. As she put it, “I can’t even focus on whatever I’m doing now, I’m just so excited.”