The wide, empty roads have a unique scent. Dry, dusty peanut butter. The brittle mingling of exhaust fumes, melting tar, and desert sand. Apricot trees climb overhead against an arid sky, the canal water from the dying Aral Sea the only antidote to their thirst.

There is a beauty to this. The openness of the land leaves room for the vastness of the sky. Jack Nicholson was right. We live in a world that has walls. But they are not the walls of a nation, the walls of security, but rather the walls of our consciousness, the walls that ride up against us on either side as we walk down Fifth Avenue in New York, or down the streets of a certain suburb of Boston. Or as we sit in our living room vegetating in front of the television. They are the literal and figurative walls which narrow the sky above us, which prevent us from staring at one end of the horizon where it converges with the earth and tracing it across the sky to the other end uninterrupted.

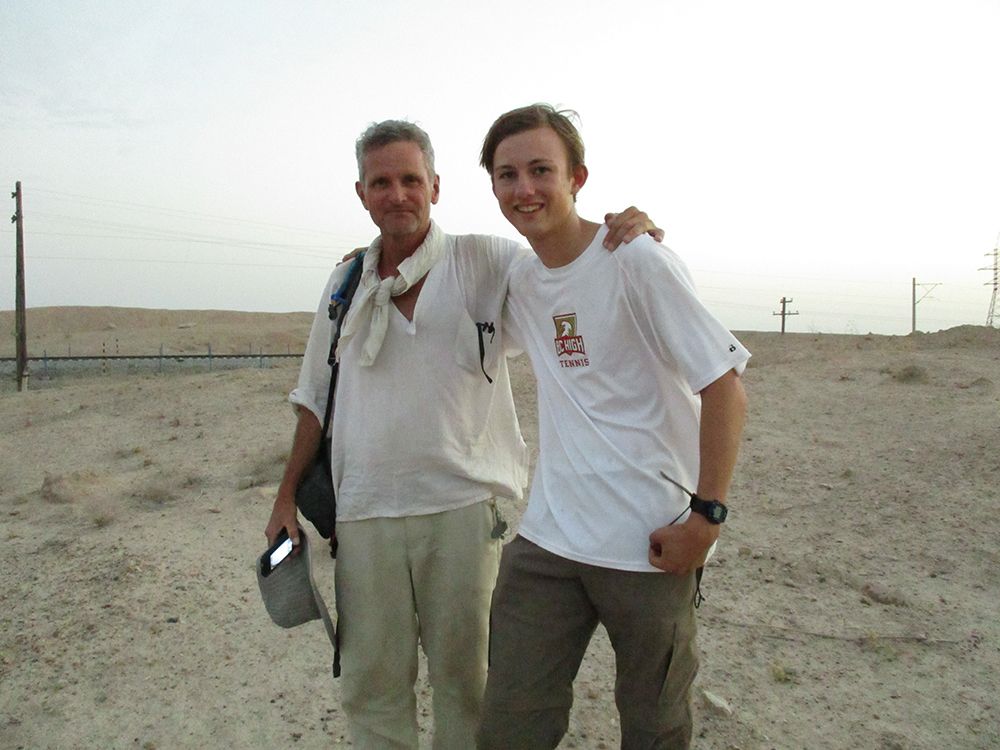

Out here, there is just you and the world. Also, two donkeys, three Tashkent teenagers, an interpreter, a chaperone, a donkey driver, the occasional antique ice cream machine, and a man walking around the world.

This is the essence of Paul Salopek's Out of Eden Walk, as I understand it. Following him on his journey for these two unforgettable days along the Silk Road east of Bukhara, we seek to break down the figurative walls in our understanding. We seek to experience the touch of a place that offers no breaks in the continuum of sky and earth but for the apricot trees.

The revelation I keep having here is how similar we all are. As Americans we often accept without question the doctrine of American Exceptionalism, the idea that America and Americans are somehow more enlightened and ahead of the rest of the world, and that the rest of the world should fall in line behind it.

We even create terms to define our supposed superiority. We maintain that we are a First World nation, the Uzbeks are Third World, somehow implying inferiority. In the original Cold War coinage, First World defined those nations that sided with us; Second World was the former Soviet Union and its allies. Third World was everyone else. More recently, Third World has come to mean those nations that lack indoor plumbing and ATMs. The conceit in pretending we don't all share the same planet—as if co-dependence doesn't define the human race, as if our development wasn't had on the backs of other nations.

This trip has for me, above all else, corroded the doctrine of American Exceptionalism. Who can claim they are more advanced than our hotelier, who this morning wouldn't let us leave his hotel until he had time to cook us a delicious complimentary breakfast? Who can claim they are more enlightened than our guide, who called us from his friend's wedding to ensure we had found our restaurant without getting lost? National greatness is qualitative, not quantitative, and there is no metric for its measure. It exists in the hospitality of a nation to strangers, in its cultures, its traditions, its rich histories, its contributions to the global community, and the way it treats and provides for its own people.

The untold story here is the breaking down of walls. How, if we abandon our preconceived notions, our unfounded hypotheses about groups of people and the individuals that comprise them, we can allow ourselves to be pleasantly surprised. In this manner we expand what Ludwig Wittgenstein once called "the limits of my world."