Late on the night of May 11, 2012, two boats converged on a river in a remote village near the Honduran coast. People in one boat, which contained an American Drug Enforcement Administration agent and two Honduran police officers, opened fire on the other vessel.

Accounts of the scene, which left four Honduran civilians dead, vary from Ahuas to Washington: the D.E.A. maintains that there was an “exchange of fire” while Honduran villagers say their neighbors were unarmed.

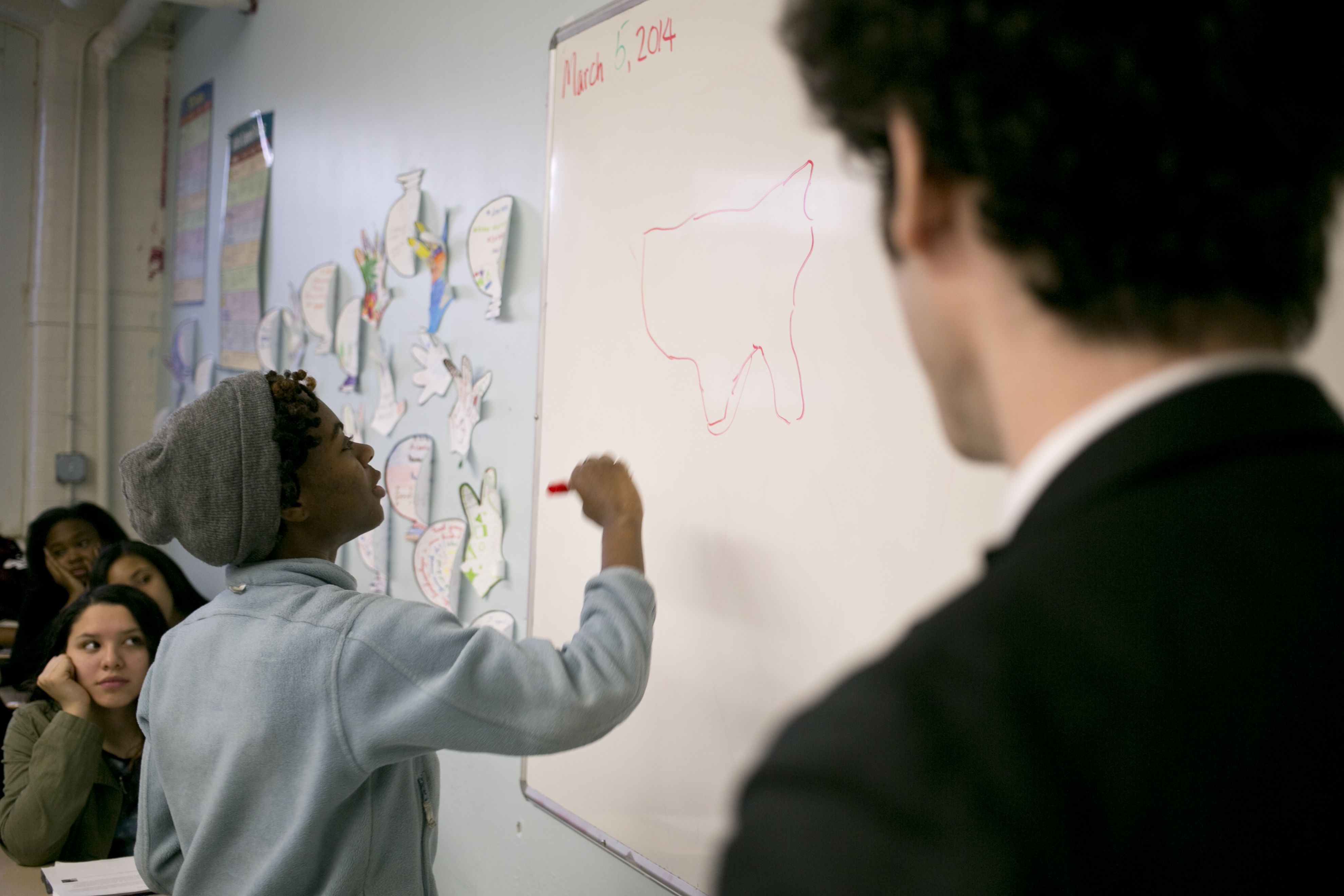

In addition to investigating the May 11 incident, freelance journalist Mattathias Schwartz's piece for the New Yorker "A Mission Gone Wrong," is a detailed and thoughtful analysis of the United States “war on drugs” and what effects that war, its protocol and its rhetoric have on the Central American people who live along trafficking routes. He spoke about the issues that drove the article with Washington, D.C. students last week in three of Beverly Clavon’s health classes at Duke Ellington School of the Arts and with global studies and Spanish students at Woodrow Wilson High School.

“What is the ‘war on drugs?’” we asked one group.

“A losing war,” a student replied.

With Mattathias’s help, students in Ms. Clavon’s classes mapped out what she called the “drug line,” tracing the long and tangled trails from the drug user back to the farmer. Much of the students’ knowledge about sourcing of illegal drugs seemed to come from movies and television shows like “Harold and Kumar” and “Breaking Bad.”

"I thought cocaine was developed here in homes like meth,” one student said afterward. “I'm glad I know now."

The discussion also addressed some mis-perceptions about places, policy and drug sourcing. Mattathias and Ms. Clavon launched a conversation about the danger of vilifying or generalizing about places and people.

“They [coca farmers in South America] are doing this process to make money to feed their babies,” Ms. Clavon said. “They are not drug lords. They’re in a supply and demand. They’re simply farmers who are providing a service.”

One student asked Mattathias whose side he was on. Mattathias explained that as a journalist he was working “the case, not the cause.”

"It was good to learn about stuff that we don't usually hear about, like where drugs come from," said a student afterward.