Common Core Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.9-10.9: Compare and contrast treatments of the same topic in several primary and secondary sources.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.1: Write arguments to support claims in an analysis of substantive topics or texts, using valid reasoning and relevant and sufficient evidence.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.3: Evaluate various explanations for actions or events and determine which explanation best accords with textual evidence, acknowledging where the text leaves matters uncertain.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RH.11-12.6: Evaluate authors’ differing points of view on the same historical event or issue by assessing the authors’ claims, reasoning, and evidence.

Objective:

You will read Scott Anderson's characterization of Wakaz Hassan, a former ISIS fighter, in order to understand how authors illustrate the complexity of a particular topic, and to compare this discussion with other Western depictions of ISIS. After reading excerpts from Anderson's piece, you will discuss the piece with your classmates, analyzing how the details he uses have influenced your perception of Hassan. In the extension activities, you will research how international law treats individuals in Hassan's situation, then apply these details and those in the piece to argue how he should be treated.

These excerpts were taken from "Fractured Lands," a special issue of the New York Times Magazine. You can read the rest of this story and learn about its production on the Pulitzer Center's website.

Warm-up Activity:

Jot down answers to the following questions. Be prepared to discuss them with the class.

1. What do you think of when someone mentions "ISIS"?

2. How do you usually see politicians and the media discussing it?

3. How do you picture the typical ISIS member?

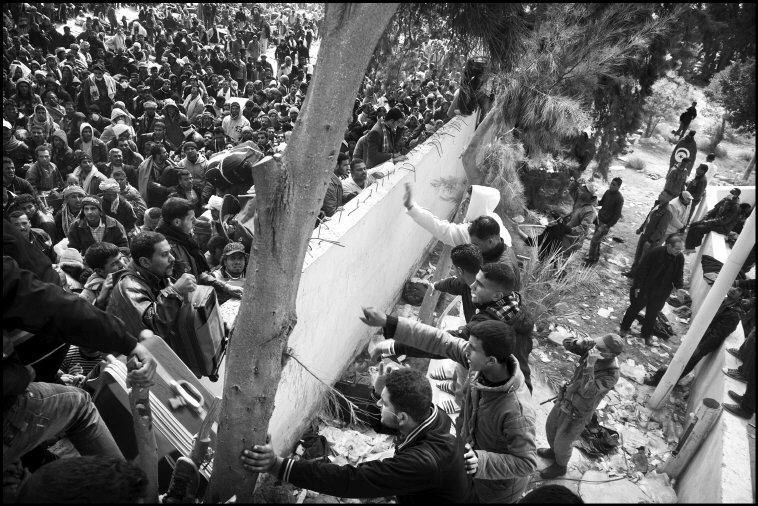

Introducing the Resource: "Fractured Lands" by Scott Anderson, with photography by Paolo Pellegrin

Read each of the following passages, jotting down answers to the Comprehension Questions as you go.

Passage 1

Wakaz Hassan always struggled in school. “I felt whenever I tried to study, I failed,” he said. At least some of his struggles might have been a result of a hearing impairment—he speaks in a loud, slightly atonal voice, often asking others to repeat themselves. But children around Tikrit were seldom tested for such things, and he simply accepted that he would never quite catch up with his classmates. After being forced to repeat a year of school, Wakaz dropped out.

By the time he was a teenager, Wakaz had joined the legions of other unskilled young Iraqi men who scraped by with day-labor construction jobs: hauling bricks, cutting rebar, mixing cement. When no construction work was to be had, he sometimes helped out in the small candy shop that his father, a retired bank clerk, had opened in Dawr, his home village just outside Tikrit. But it was all a rather meager and dull existence.

...But in June 2014, a series of cataclysmic events were about to break over the Sunni heartland of Iraq, and they would radically alter the fortunes of the 19-year-old day laborer in Dawr.

At the very beginning of that year, ISIS insurgents wrested control of the crucial crossroads city of Falluja in Iraq’s Anbar Province, then spread out to seize a number of nearby cities and towns. At the time, Wakaz knew very little about the group, other than that it sought to establish an Islamic caliphate in the Sunni lands of Iraq and Syria. Over subsequent months, however, Wakaz, like most other young Tikriti men, had seen the elaborate recruitment videos that ISIS produced and distributed on social media. The videos depicted warriors, or “knights,” as ISIS called them, clad in smartly turned-out uniforms and black ski masks as they rode triumphantly through towns they had conquered, great black flags flapping from their new Toyota Land Cruisers. Other videos from that time showed a decidedly darker side of ISIS—executions and crucifixion displays—but Wakaz claimed never to have seen those.

Omitted from Wakaz’s account was the matter of money. By the summer of 2014, ISIS was so flush with funds from its control of the oil fields of eastern Syria that it could offer even untrained foot soldiers up to $400 a month for enlisting—vastly more than an unskilled 19-year-old like Wakaz could make from pickup construction jobs.

“They showed me how to do it,” Wakaz said. “You point the gun downward. Also to not shoot directly at the center of the head, but to go a little bit off to one side.”

In the training-compound field, Wakaz dutifully carried out his first execution. Over the following few weeks, he was summoned to the field five more times, to murder five more blindfolded and handcuffed men. “I didn’t know anything about them,” he said, “but I would say they ranged in age from about 35 to maybe 70. After that first one, only one other was crying. With the others, I think maybe they didn’t know what was about to happen.”

Wakaz related all this—even physically acted out how a proper killing was done—with no visible emotion. But then, as if belatedly realizing the coldbloodedness of his account, he gave a small shrug.

“I felt bad doing it,” he said, “but I had no choice. Once we reached Mosul, there was no way to leave—and with ISIS, if you don’t obey, they kill you too.”

In June 2015, Wakaz's one-year tour of duty with ISIS ended. He decided not to re-apply, and instead fled to Iraqi Kurdistan, hoping to start a new life. Upon his arrival, however, he was quickly arrested by Asayish, the Kurdish security services.

After his arrest, Wakaz quickly confessed to having been an ISIS fighter. He provided details of his service, including the six executions he carried out in Mosul. Whether this confession was coerced through torture was impossible to know—in conversation with me in the prison, Wakaz insisted that the Asayish interrogators hadn’t mistreated him in any way, but even tortured prisoners tend to say that when their captors are standing over them. Over the course of our two long interviews, the young man sometimes contradicted himself, perhaps a result of trying to gauge what his questioner and captors might want to hear. That said, there seemed a core candor to his words that perhaps was at least partly because of a stricken conscience.

“I did bad things,” he told me, “and I need to confess to them before God.”

Shortly after his arrest, Wakaz also informed on his brother Mohammed. It took Asayish a month to track down the older Hassan sibling, and he was being held in a different prison near Kirkuk. There had been no contact between the brothers since their arrests, but Wakaz hoped Mohammed was also making a clean slate of things. His main goal now, he said, was to atone for his crimes by helping the authorities identify whichever of his former ISIS colleagues were still alive. “If I had a chance to do it over again,” he said, “I never would have joined Daesh. I saw the evil things they did, and I know now that they aren’t true Muslims.”

Despite this professed change of heart, the 21-year-old is cleareyed about his future. “I have no illusions, and I have no hope,” he told me. “I believe I will spend the rest of my life in prison.”

But Wakaz was basing that belief on the fact that he had been captured by K.R.G. investigators and remained in Kurdish custody….Once his usefulness to Asayish comes to an end—and that may not be until after the retaking of Mosul and the trove of ISIS fighters expected to surrender there—Wakaz will be handed over to the Iraqi authorities. At that point, his future will be short and preordained.

“He thinks his life will be saved because we have him, and he knows we don’t execute,” the Asayish officer said. “But Iraq does. The Iraqis will try him in their courts, and they will give him a death sentence. Then they will transfer him to a prison in Iraq to be hanged.”

When I asked if there was any chance that, because of Wakaz’s assistance in unmasking other ISIS fighters, a judge might show leniency in his case, the Asayish officer quickly shook his head. Or that he could somehow cut a deal to spare his life? The officer pondered briefly, then shook his head even more forcefully.

“If he was senior Daesh, maybe,” he said. “But he is a nobody and poor. So no. No chance.”

Write down answers to the following Extension Questions. Be prepared to discuss your responses.

1. Look back at your response to Warm-Up Question #2. How does this portrayal of Wakaz compare to other widespread depictions of ISIS?

2. Do you think Wakaz's likely punishment is just? Which details lead you to that conclusion?

3. How would you describe Anderson's attitude towards Wakaz? Why? What evidence from the article demonstrates how Anderson feels about Wakaz?

Extension Activity:

1. Research the Nuremburg Trials that were held for Nazi war criminals after World War II, noting the "Superior Orders Defense" and its use in subsequent trials.

2. Write an essay arguing whether or not Wakaz's life should be spared, drawing on your research and the details in Anderson's narrative that you applied in the extension questions.

The following lesson plan asks students to analyze how Scott Anderson, author of "Fractured Lands," characterizes Wakaz Hassan, a former ISIS fighter. The four passages included with this lesson plan detail Wakaz's youth, his decision to join ISIS, his first execution and his current situation in prison. Students begin by recalling what they know about ISIS, and the way politicians and the media generally depict the group. As students read the four passages, the comprehension questions help them understand the devices Anderson uses to demonstrate the complexity of Wakaz's circumstances. After reading, students compare and contrast this account with other characterizations of ISIS, and analyze how Anderson's reporting has shaped their attitudes towards Wakaz. In the extension activity, students apply details from the piece, along with their own research, to create a persuasive essay on whether or not Wakaz should be hanged for his actions.