Introduction: What Is a Primary Source?

- Have you heard the term primary sources before? In what context?

- What are examples of primary sources?

- What are the differences between primary and secondary sources?

Background: Residential Schools

- When you hear the term “residential school,” what do you think of?

- In Canada, this term refers to the Indian Residential Schools, a network designed to assimilate indigenous students into western Canadian culture. For over 100 years, young indigenous children were removed from their families and placed in church-run boarding schools where they were punished for participating in any indigenous cultural traditions and subjected to assault, abuse, and in some extreme cases, medical experimentation and sterilization.

- Read the first five articles from the resource section (listen to the audio from resource 5) and this essay from the University of British Columbia to learn more about the residential schools and their impact on Canada’s indigenous population.

- Use the following questions to spur discussion about the resources:

- Why did the Canadian government force indigenous children into residential schools? What was the goal of this educational policy?

- What were the conditions in the residential schools?

- What was and is the impact of this policy on Aboriginal families, children, and culture?

- Are these resources primary or secondary sources?

- Additional resources: The residential school network was one part of Canadian policy regulating indigenous peoples. To read more about Canada’s Indian Act, visit this webpage.

Activity: Analyzing Photographs as Primary Sources

- Assign each student or group of students a different province or region from the Library and Archives Canada’s photographic collection of Indian Residential School.

- Look at the photographs and analyze each one. Try to determine

- Who created it?

- When and where was it taken?

- What does it show? (What is it intended to show?)

- Why is it historically significant?

- Have the students share their analysis of the photos they reviewed.

- Use the following questions to spur discussion about the resources:

- Who were these photographs for and why were they taken?

- Based ONLY on these images, how would you view the Canadian Indian Residential Schools?

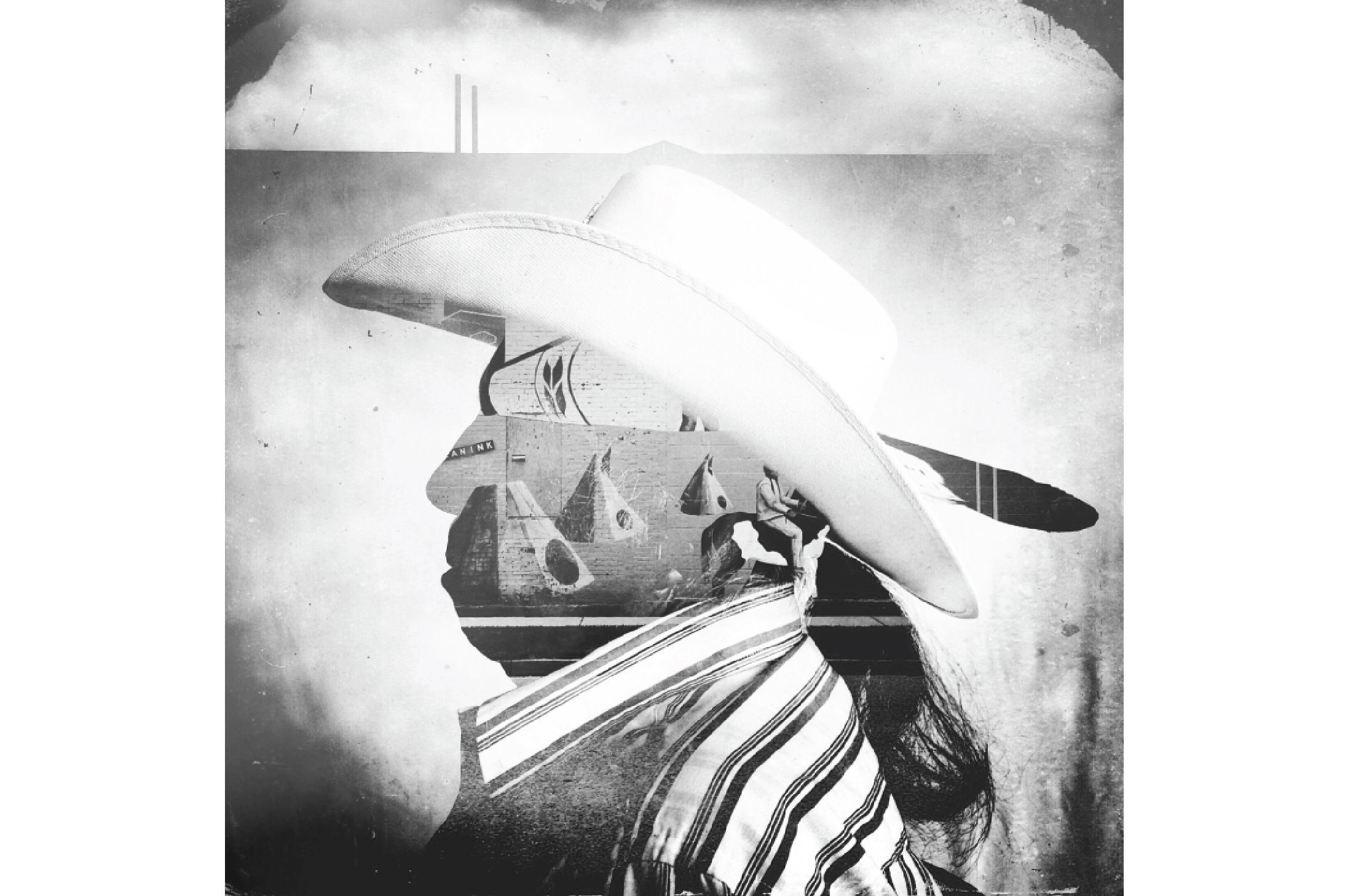

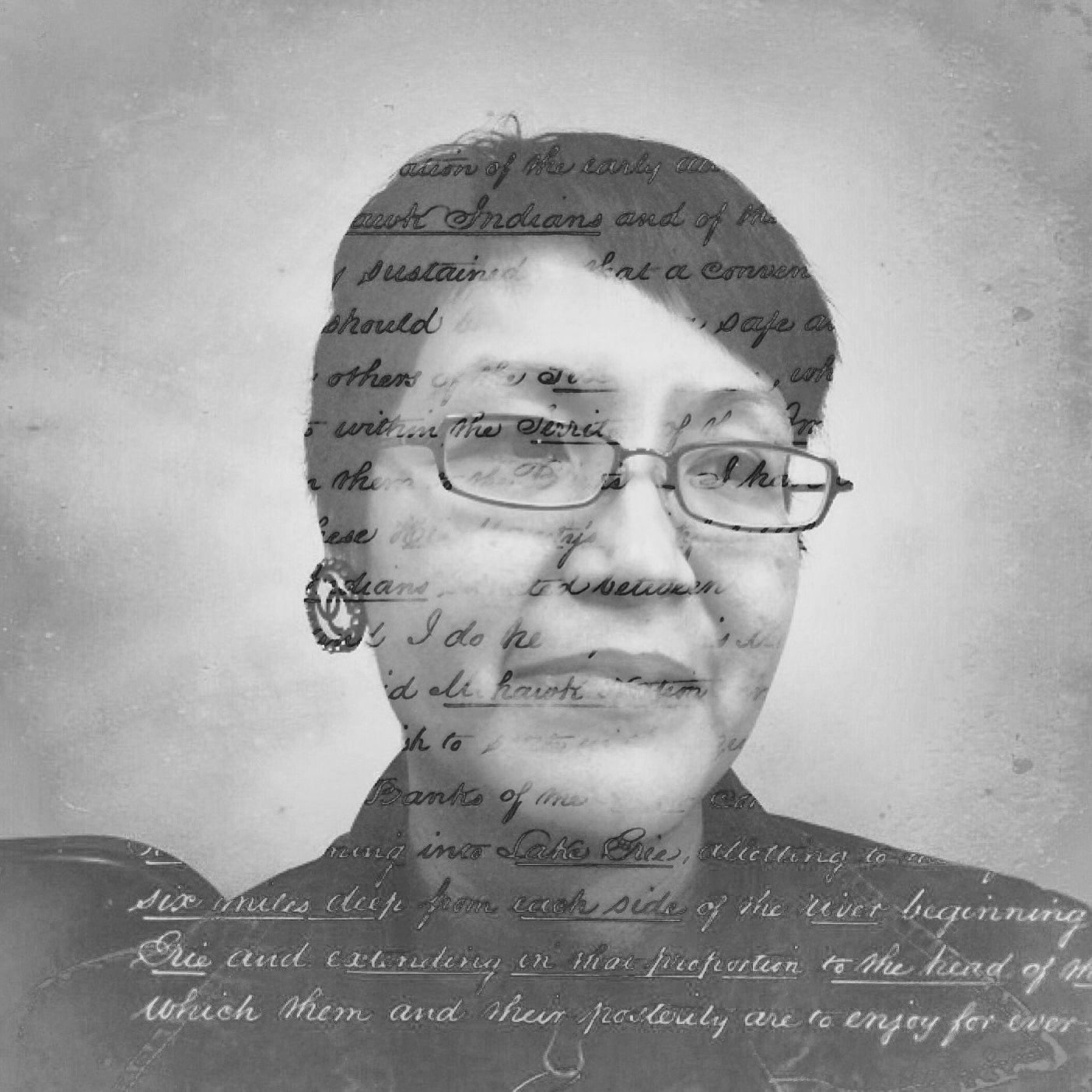

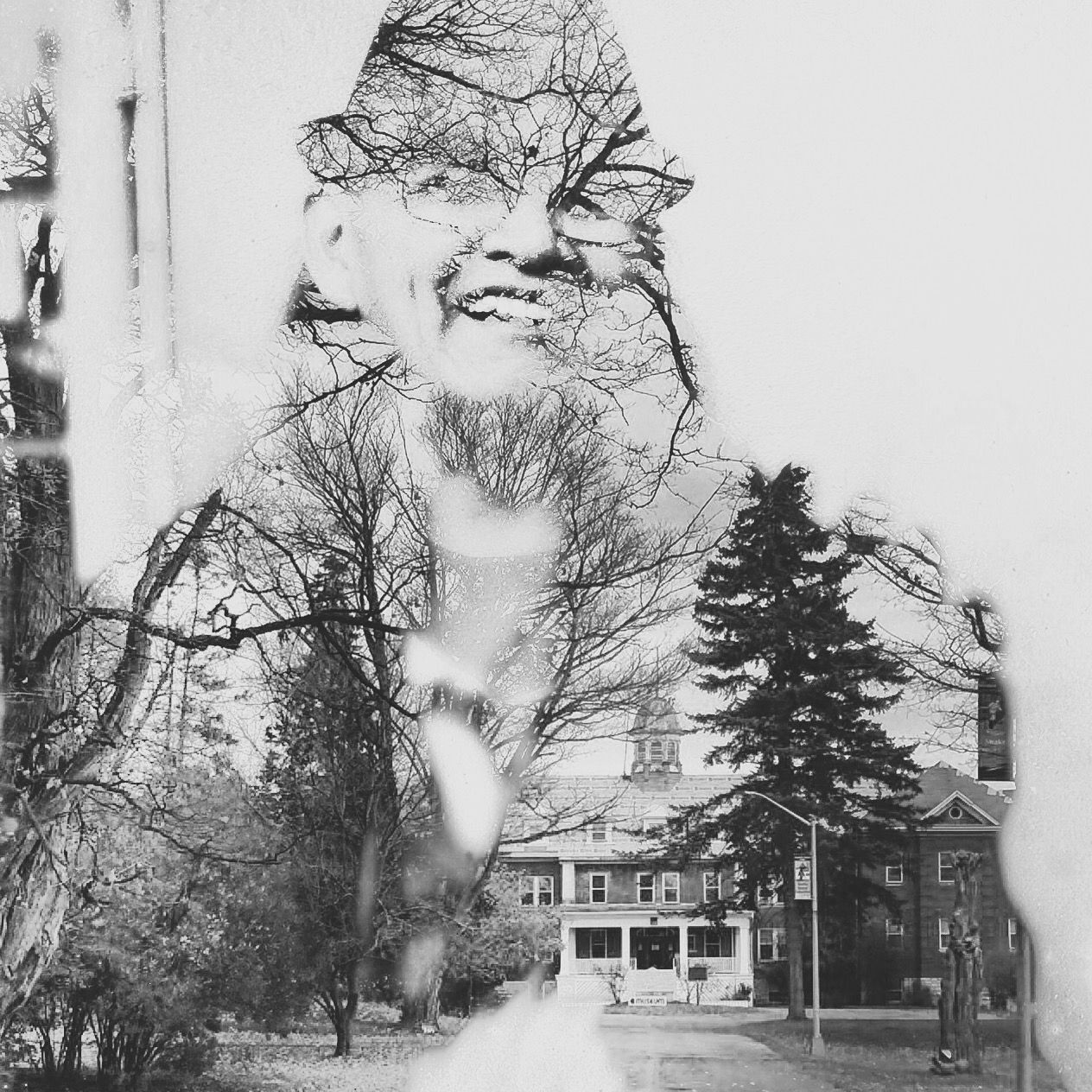

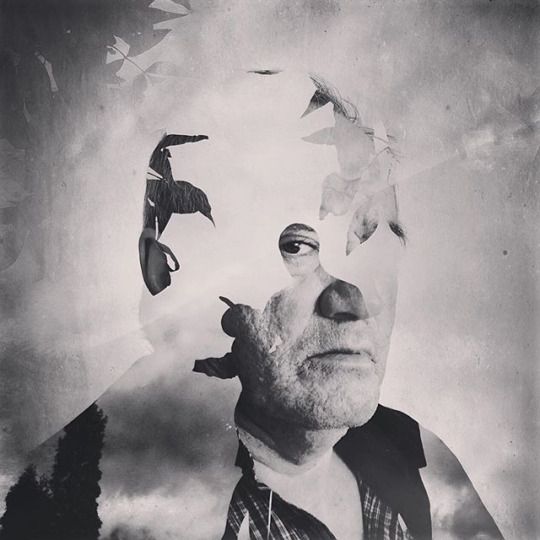

- View Daniella Zalcman’s photographs of survivors of residential schools. The images can be viewed via the final lesson plan resource, the New Yorker website, and the National Geographic website. Each resource contains some different images and information so look at all three.

- Look at the photographs and analyze each one.

- What technique does Daniella Zalcman use in these photographs and why?

- What does each photograph show? (What is it intended to show?)

- Who are these images intended for?

- Why are the photographs and the accompanying interview excerpts historically significant?

- What challenges did Daniella Zalcman grapple with while working on this project?

- Think about both sets of photographs.

- What are the similarities and differences between these photographs?

- Based on all the material you read and viewed as part of the lesson, how do you view the Canadian Indian Residential Schools?

- How do you reconcile the two sets of images along with the information presented in the background reading and interviews?

- Why is it important to view, read, or listen to more than one source?

- How can people documenting the past incorporate voices and experiences often overlooked in historical studies?

- How can a person engage with a person from another culture sensitively? How can we respect other people’s cultural backgrounds and their experiences?

Wrap-Up: Thinking Further

- Should the Canadian government mitigate the effect of residential school policy, and if so, how does it do that?

- How does what you learn today impact how you think about Aboriginal culture in Canada? Does it impact how you think about the Canadian government or religious groups that participated in the residential school system?

This lesson plan can be modified to use written primary sources found on the Signs of Your Identity website. Assign students different government documents to read in class or for homework, and have them present their analysis to the class. This can be in place of analyzing images, or in addition, to the activities in this lesson plan.

This lesson plan is designed for a two-hour class. The lesson could be divided over two days, one day to read and discuss and one day for analysis and presentation, or reading and analysis could be assigned for homework while discussion and presentation occur in class for one day.

Additional education resources are available at the Signs of Your Identity website. Visit the For Teachers section for potential opportunities to engage with the project and Daniella Zalcman.

Introduction: What Is a Primary Source?

Ask your students the questions. Based on their answers, provide a refresher on primary sources and their use. Do the same for secondary sources.

Background: Residential Schools

Note to your students that it was not just Canada that had this policy, many other British colonial holdings did as well. The United States government authorized similar policy in the late 19th century. A good summary and collection of photographs can be found at here. Another way to expand or modify the lesson plan would be to include these images and information. Have your students read Daniella’s article from the Smithsonian magazine and analyze images from it along with those from the website above or from this Library of Congress collection.

Activity: Analyzing Photographs as Primary Sources

Remind students that photographs are often posed, even ones designed to be candid. If you want to engage in a more philosophical debate, have them discuss if a photograph can ever truly be candid if the subject knows that the image is being taken.

During the discussion of the archive photographs, remind students that these photos would most likely be taken for use by governmental agencies to pursuade officials and the public that these schools were “working.” There would be an interest in depicting students as compliant and the conditions as acceptable.

During the discussion of Daniella’s photographs, refer students back to the first lesson plan resource if they need a refresher on her technique and why she used it.

Evaluation:

Evaluate students based on participation in discussion. Another method of evaluation, have students write up ~500 words addressing one or more of the wrap-up discussion questions. Another option, have them analyze a different primary source related to this lesson plan.