Introducing the Lesson:

What happens when after 13 years a foreign fighting force pulls out of a country and the world turns its attention elsewhere? Life goes on, of course.

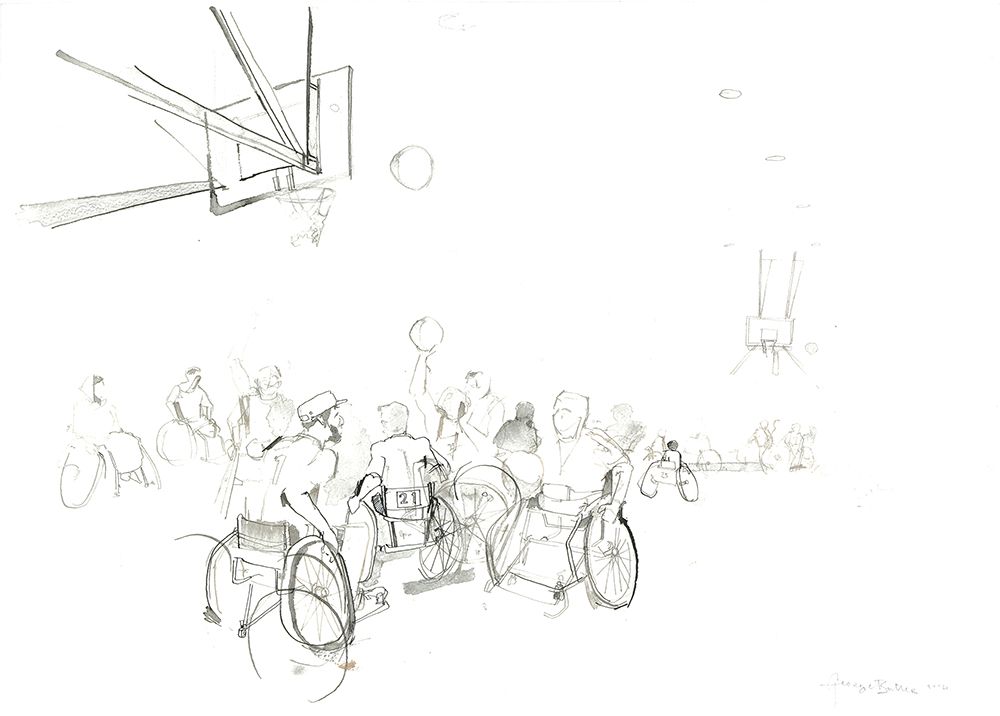

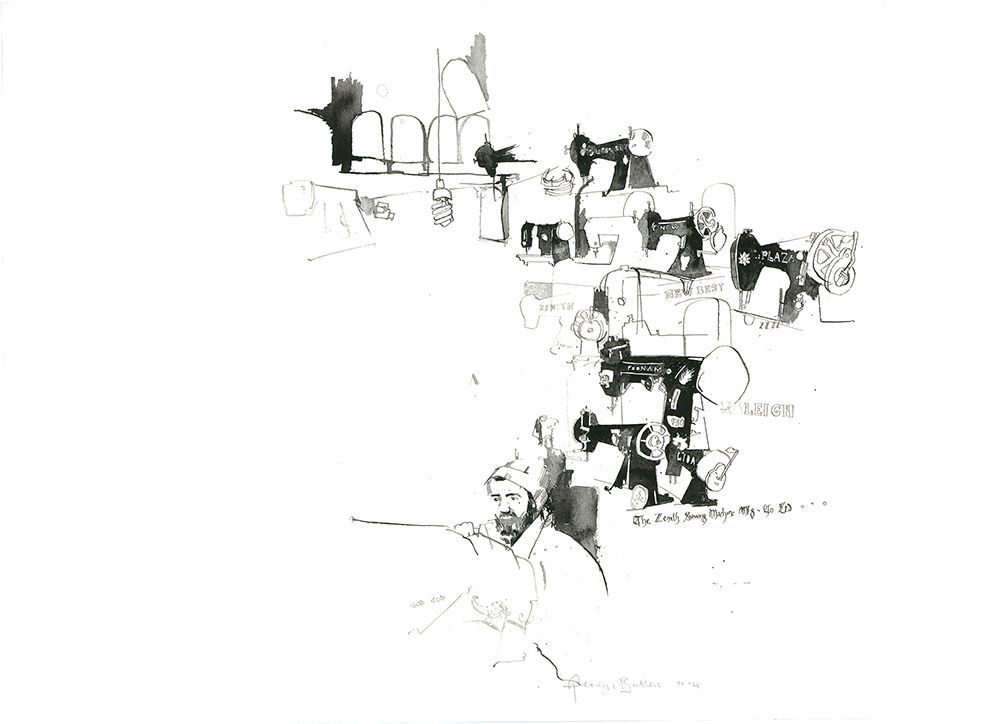

In October 2014, U.S. and British military operations in Afghanistan came to an “official” end. George Butler, a reportage illustrator, saw Afghanistan for the first time at age 22 as a guest of the British Army. But on his most recent trip, in 2014, he went without a military escort. Butler wanted to see as “real” an Afghanistan as possible as the world withdrew from the country. The methods and tools Butler uses for his reporting -- blank sheets of paper, a pen, and ink -- allow him time and a kind of intimate access to daily life that other journalists can’t always achieve. And as an artist, he looks for the “everyday” story, one beyond those we typically see in the news media.

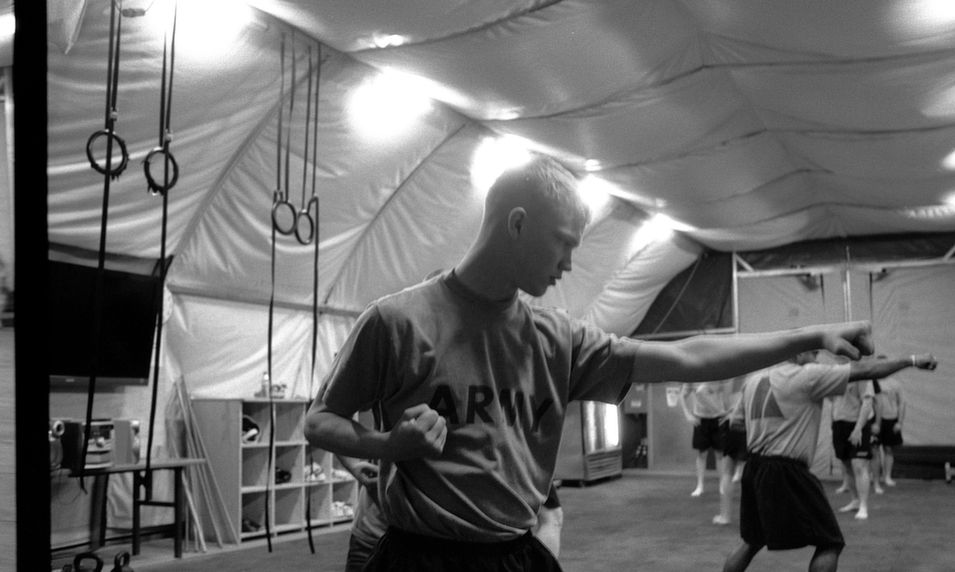

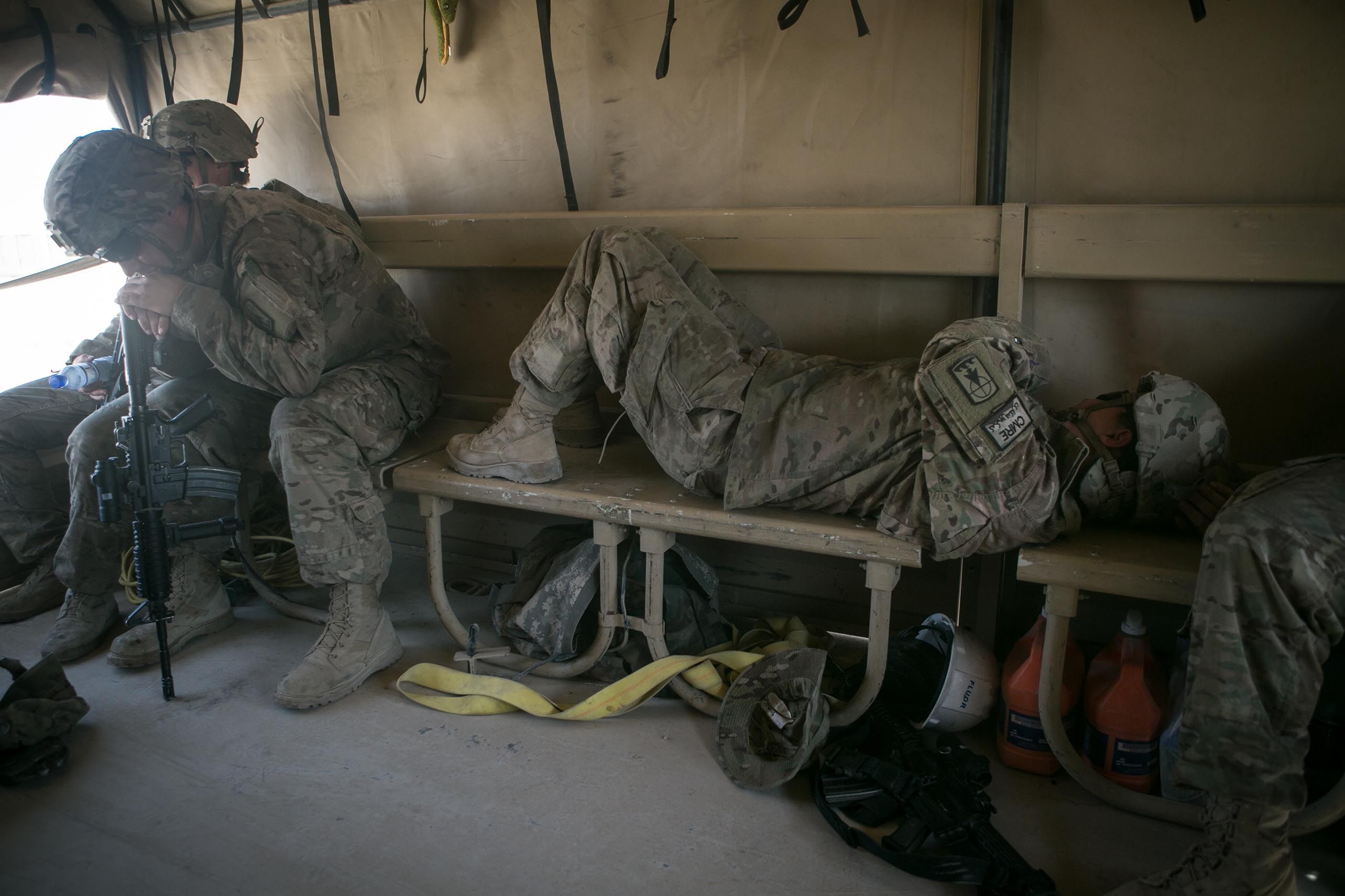

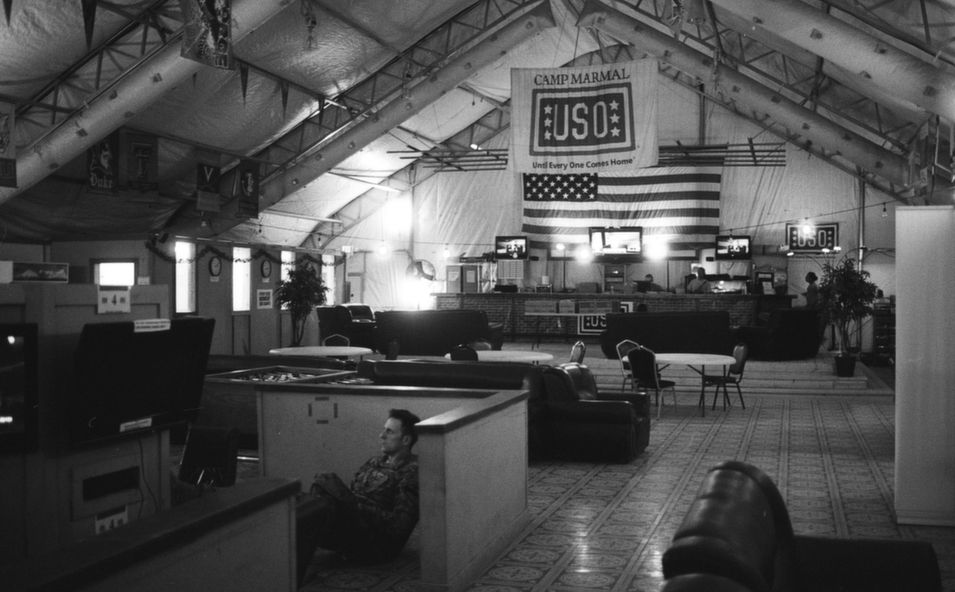

Meghan Dhaliwal and Meg Jones, an American photojournalist and reporter, respectively, embedded for two weeks in Afghanistan on several U.S. military bases with a Wisconsin National Guard unit, the 829th Engineer Company in charge of -- literally -- packing up the war, dismantling tents and beds, shipping Humvees and computers and refrigerators out of the country. Much like Butler on his first trip, as Dhaliwal snapped photos on the bases she was accompanied by an escort.

Butler and the Dhaliwal-Jones team watched the end of a war from opposite sides of the fence. In this lesson we’ll explore the ways in which visual resources can share different information and some of the challenges journalists face when trying to capture all sides of a story.

Essential Questions:

1. What are the central ideas of these "texts" (reportage illustrator George Butler's drawings and photographer Meghan Dhaliwal's images from Afghanistan)? How does each journalist convey these main ideas?

2. What are some important ways in which reportage drawing and photojournalism differ? What are some things we, the audience, get from Butler’s drawings that we wouldn’t get in photographs? What do Dhaliwal’s photographs provide that we don’t get in the drawings?

3. Consider the quotation below. What does it mean? How does Butler’s work address it? What about Dhaliwal’s?

“We have never been closer to, nor further away from, the reality of war.”

-Steve Bloomfield

4. Consider this excerpt from Butler in the Guardian:

“Almost each day I spent in Kabul, there was an explosion or an attack from an armed group. But I soon realised that, despite the uncertainty and insecurity, the majority of Afghan life continues to be as close to normal as possible. It was this Afghanistan that I found overwhelmingly inspirational to document. What saddened me was that so many of the articles and reports I read before I arrived – although consistently accurate in detail and honest in their approach – made me expect the worst. This was far from the case in the small parts of Afghanistan I saw, especially in the north and west, away from Helmand and other parts of the south and east, where most of the reports seen on our televisions in UK have come from.”

What is he saying here about the way foreign news, particularly war, is covered in the Global West? How does Butler hope his work will counter those narratives?

5. Read this excerpt by Meg Jones, the writer who worked with Dhaliwal, about the U.S. war equipment used in Afghanistan:

“Some equipment will be given to Afghan security forces; building materials like plywood will be offered to Afghan civilians. Items that have outlived their usefulness or are so degraded that they're worthless will be destroyed. And a lot of equipment will return to the United States, including mine-resistant ambush-protected (MRAP) combat trucks, which will be given to law enforcement agencies in the United States under a Defense Department program that has caused controversy recently following the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, as some question why communities need to arm their police departments with such massive firepower.”

How does this passage by Jones bring the war “home”? How do Dhaliwal’s photographs illustrate the strength and power of these war tools? Do you get a similar feeling about war and military strength when you look at Butler’s drawings? Why or why not?

Conclusion:

In a short essay, compare and contrast the work by Dhaliwal and Butler in Afghanistan. Do you feel that one set of images conveyed its point better than the other? If so, why? What is strong about each set of images? What would you have done differently as the journalist?

Students will compare two kinds of visual journalism documenting the end of the war in Afghanistan.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.2

Determine a central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.6.9

Compare and contrast one author's presentation of events with that of another (e.g., a memoir written by and a biography on the same person).

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.3

Analyze how a text makes connections among and distinctions between individuals, ideas, or events (e.g., through comparisons, analogies, or categories).

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RI.8.7

Evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of using different mediums (e.g., print or digital text, video, multimedia) to present a particular topic or idea.