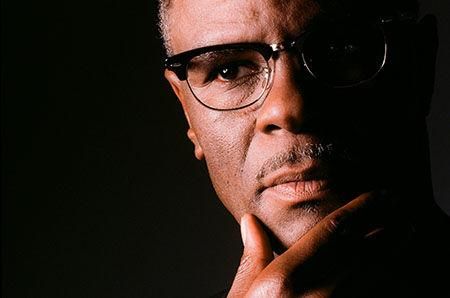

I have been writing about 63106 – one of our city’s most impoverished tracts – for almost as long as I have lived there. But never at the same time.

Not until now. Not until the inception of the 63106 Project. It’s a racial equity storytelling venture focusing on families in neighborhoods with a documented history of economic and health disparities. I grew up in one of those families.

I spent my early childhood years in the Pruitt-Igoe public housing complex, then, at the age of about 10, moved with my family to the Old North neighborhood just outside 63106.

Later, I moved on, but often wrote about my old neighborhood as a columnist for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and as a free-lance writer.

But now I am back, living in an apartment a few blocks from the iconic Crown Candy Kitchen.

Am I as marginalized and at risk as my neighbors? No. I make a small income that allows me to get by and when I have something to say, I can command a decent-sized audience either through a story in mainstream media or through social media.

By contrast most of my neighbors are among the unheard. Many are dealing with health issues and rely on food stamps and Medicaid. Some have no health coverage at all.

The 63106 Project has given me a unique opportunity to share the stories of my neighbors with you. In me, my neighbors have a narrator who can listen with understanding and empathy. In me, readers have someone who very much knows the territory.

Growing up in and near 63106 was challenging. Well that’s what an adult would say. Scary is how I saw it as a child.

I remember the absolute terror I felt the first time I crossed the 11th Street bridge high above Interstate Hwy 70 to attend the now-shuttered Webster Elementary School at 2127 North 11th Street. Keep in mind, as a little kid in the projects, I’d never seen a highway. My imagination had me easily toppling over the chest-high chain link fencing to a horrible death in morning rush hour traffic. More secure fencing has been constructed around the walking bridge now.

In terms of poverty, nothing much has changed since I left the neighborhood some 50 years ago. The starkest difference is the change in demographics. Back then, it was an area dominated by poor whites, some with Irish and German ancestry. It was the first neighborhood where I heard the N-word uttered as an assault on my existence. Oh, I had heard the word as a tyke from my father, his friends, and relatives, but it was said in a jovial, self-mocking manner. I first experienced it in a sinister, threatening way when a car full of white teens shouted it at me and my older brother, Daniel.

It got worse. It was on Ninth Street, near the railroad tracks, shortly after we moved there, that my father, driving while intoxicated, struck and injured a white man. My mother, Daniel and I were on the scene when a big-bellied, red-faced cop arrived. Slapping his nightstick in his beefy hand he asked my father: “Are you drunk, Ni...er?”

As more cops arrived, my mother rushed us from the scene. We couldn’t see what was behind us, but the sounds of my father’s screams and pleas mixed with the hateful racial expletives from those cops haunt me to this day.

I have some sweet memories, too. My siblings and I were but a handful of black children at Webster. I fondly remember, Miss Link, a young, compassionate white teacher who came out to the school yard to greet, hug, and welcome us to school every morning until we were acclimated.

The 14th Street shopping district in Old North was declining back in the days of my youth. Small stores were closing but there were still a few shops where you could buy toys and comic books and, of course, huge mouth-watering ice cream cones from Crown Candy.

Now, due to the efforts of young rehabbers and historic preservation organizations like the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group, the area is coming back to life. This will probably accelerate as 63106 is also in the footprint of the $1.7 billion National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency project.

When I joined the St. Louis Post-Dispatch as a columnist my editor, Dick Weiss, upon learning of my connection to Pruitt-Igoe, encouraged me to write a series on the complex beginning with its construction in the mid-1950s and ultimate demolition in the mid-1970s. That series served as inspiration for the producers of the “Pruitt-Igoe Myth” documentary.

Dick and I have since moved on from the Post-Dispatch, but have always kept in touch. As he was developing the idea for the 63106 Project, he reached out to me and became even more enthusiastic when he learned that I had moved back to my old neighborhood. Since then we have been batting ideas back and forth. The accompanying story about Jamaica Ray is just one of many to come and will continue over the course of the pandemic.

Let the adventure begin.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.