Mohammed Shabud Ali was attacked by a tiger on July 24, 2010. He considers himself lucky to be alive.

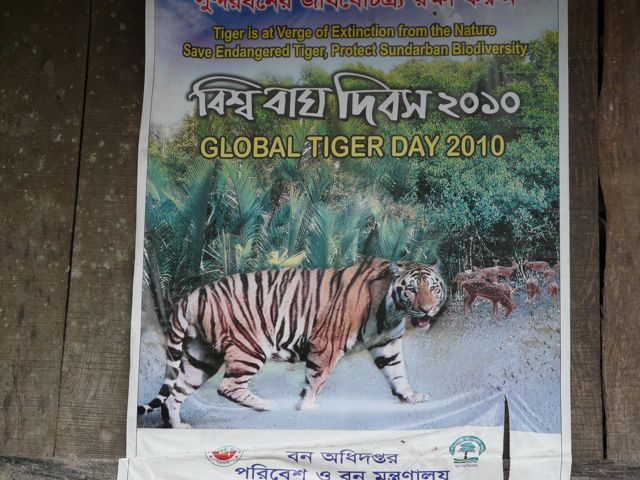

The Sundarban mangrove forest, home to an estimated 500 endangered Royal Bengal Tigers, is a case study in the unforeseen effects of climate change. Seawater has ruined rice farms in the area, and in recent years many farmers have sold their land for next to nothing. Others converted it to shrimp farming, which requires a brackish mix of fresh and salt water. But now it has become too saline for that, and those who remain are increasingly turning to fishing. Now the seas and rivers are overfished, forcing fishermen to venture deeper into the mangrove forest – where the tigers are experiencing shrinking habitat as well. Tigers now kill approximately 120 people per year in this area, with many more injured in attacks.

Like almost all of Bangladesh, the area is heavily populated. Tigers increasingly cross the river and enter villages looking for food (human or livestock). We saw a video of one that was trapped on the roof of a hut, hanged, and beaten by a frenzied mob, who live with the constant fear of attacks. Even as the dead tiger was dragged away, men ran up with clubs and pounded the body.

Working closely with a local NGO called LEDARS, which supports "tiger widows" and helps locals adapt to the challenges of climate change, we sought to learn more about the growing tiger-human confrontation. We took a boat out to an elevated mud embankment in a place called Gabura to visit a tiger attack survivor. The area was slammed by Cyclone Aila in May 2009 and has been largely underwater ever since. We had to slog through knee-deep mud to get from the boat to the embankment, and then the villagers helped pull us atop it. It was so slippery that every step bore the possibility of falling face first into the muck, which was laced with broken glass.

The survivor, Mohammed Shabud Ali, is a fisherman who had been attacked four weeks earlier while navigating his boat through the mangrove forest. When we arrived, he was lying on his side in a hut with his face at the door -- he still couldn't lie on his back, because tigers attack from behind, and his injuries were severe. His wife and sister-in-law tended to him. The tiny hut barely had enough room for cameraman Steve Sapienza and translator Mainul Khan to squeeze in for the interview.

Ali says he feels lucky to have survived the attack. He knew another fisherman who was eaten by a tiger. He attributes his survival to sensing the tiger's presence and turning just as it leapt onto his back. He also had several other fishermen nearby, who helped distract the tiger while he somehow scrambled back into the boat.

He does not know when he will be able to return to work.

The next day we interviewed Rasheeda Khatune, a tiger widow whose husband had survived a mauling 10 years ago, only to be attacked again two years ago while fishing, this time fatally. Tiger widows are sometimes stigmatized as "bad luck," and ostracized by the community, thus suffering doubly. Rasheeda said this was not the case for her, that since her husband had been attacked twice, people just considered that it was "his fate" to die that way.

She told us that she often hears tigers snarling at night from across the river. During the summer monsoon season the river is quite wide – I would estimate a third of a mile – but in winter it recedes to half that width, and tigers are excellent swimmers.

She has two young boys and a 22-year-old son, Rasinur Mohammed, who carries on in his father's footsteps, largely because there are few other options now. We filmed with him later that day as he paddled off in his small wooden boat to go fishing.

I had read how the fishermen and honey collectors who venture into the Sundarbans are stoic and unafraid, as men who routinely face occupational danger are often reported to be. As Rasinur's boat nosed into the dense mangroves, he began to look over his shoulder nervously – and often. "Yes, I am afraid of the tigers after what happened to my father," he told us matter-of-factly. I found his honesty refreshing.

NOTE: I've just received a "breaking news" alert from LEDARS that a tiger has crossed the river and entered the village of Chunkuri, Munshigonj Union. The Bangladesh Forest Department's Tiger Response Team has been summoned, and every effort is being made to protect the tiger until they can arrive, tranquilize it, and return it to the protected part of the Sundarbans.

NOTE 2: A second alert from LEDARS says the tiger killed three goats and a dog before returning to the forest on its own, before the Tiger Response Team could get there. It has reportedly made five visits to the village over the last eight days, and residents are extremely anxious about its likely return.