At face value, Daniella Zalcman’s new book, Signs of Your Identity explores the deep trauma that residential schools inflicted on the Indigenous students who were forced to attend them in Canada throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The book goes much deeper than that though, exploring the construction of cross-cultural identities, trauma, and resilience. Her images thoughtfully combine portraits with elements of the landscapes where the schools were located. The intersection starts to speak to larger narratives about historical rights and legacies in addition to the individual experiences.

We spoke with Zalcman about her process via email.

Can you speak a bit about your process of choosing which images would be superimposed?

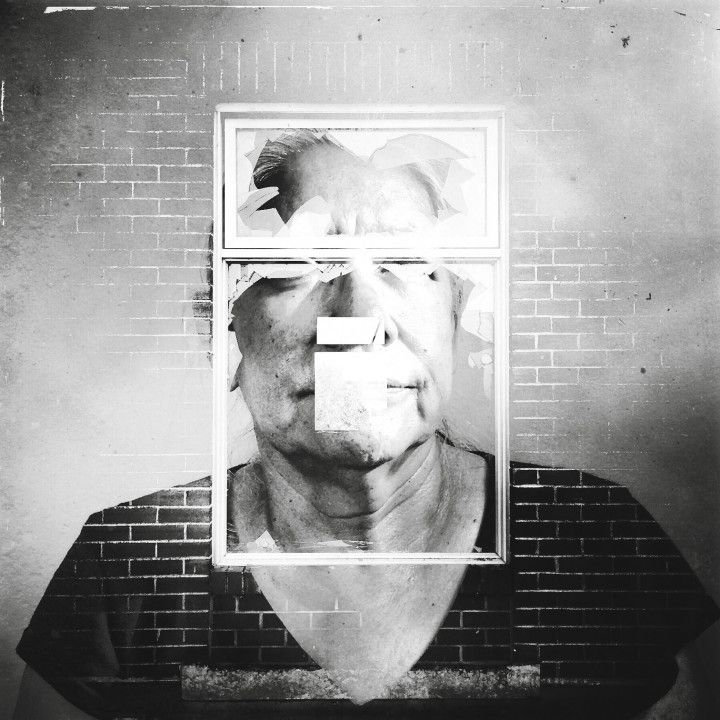

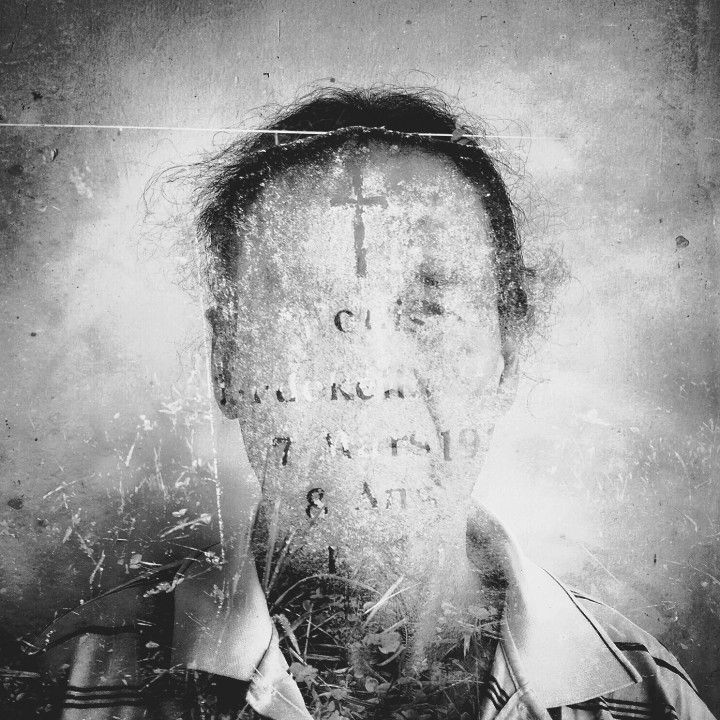

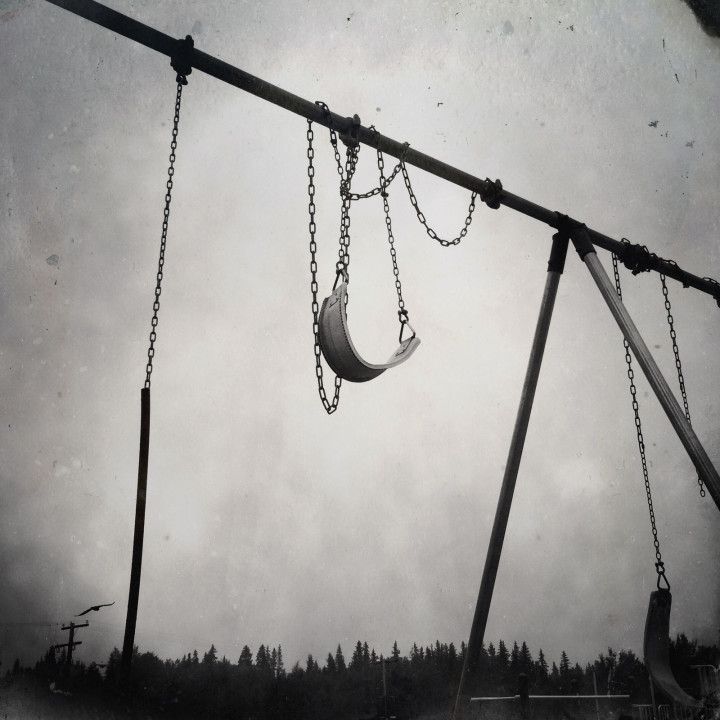

Daniella Zalcman: For every survivor I met, I’d interview him or her first, with a conversation that would last anywhere from 15 minutes to 3 hours, take a few portraits, and then go in search of an image that was somehow evocative of that person’s experience in residential school. Sometimes they’re very literal — the broken window from the dilapidated remains of Muskowekwan Indian Residential School where Valerie Ewenin was a student, the river near Beauval Indian Residential School where several of Joseph Edechanchyonce’s friends drowned while trying to escape. Others are more metaphorical, more rooted in memory and emotion. But there’s always a particular and specific logic to why each person is paired with that specific secondary image.

What first got you interested in this subject?

DZ: I ended up in Canada in October to November 2014 chasing a public health story. I’d read a report that Indigenous Canadians have one of the fastest growing rates of HIV in the world, and that shocked me. Canada is wealthy, has a fantastic health care system, was an early adopter of a lot of progressive harm-reduction strategies like free needle exchanges and safe injection sites. So the fact that there was this massive epidemic, that an entire population was being left behind, was stunning to me. I spent a month traveling through British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Ontario — and at least 90% of the HIV positive Indigenous people I interviewed referenced residential school. I’d never heard of Indian boarding schools before, and once I started learning more about the system I was horrified and ashamed that it had been so thoroughly erased from American history textbooks.

How long were you working on it?

DZ: The images that went into the book were all made during a two-week trip to Saskatchewan in August 2015. But the idea and the research that went into the book were about a year in the making. And I’m still working on the project now — I’ve spent several months so far on the US chapter photographing and interviewing in Navajo and Lakota communities, and plan on visiting roughly eight more countries that had similar school systems.

Did subject lead concept, or vice versa?

DZ: I got back from my trip in 2014 and realized that a lot of the images that I’d made weren’t successful. It was an accurate depiction of the systemic crises that many Indigenous communities are fighting, and certainly those crises are part of the bigger legacy of cultural genocide and forced assimilation, but the images alone didn’t convey that. There were a lot of photos of First Nations Canadians struggling with substance addiction and poverty, and those images felt stigmatizing and two-dimensional without the greater context of what happened at these schools.

So when I went back a year later, I realized that I needed to try something different. I couldn’t photograph in the schools, because they no longer existed, and I’d tried to photograph the legacy itself and that didn’t work either. So I realized that for me, the best way to tell this story about memory and intergenerational trauma and the things we pass from parent to child was through multiple exposure portraits.

The project, which was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, includes the statement:

For more than a century, the Canadian government operated a network of Indian Residential Schools that were meant to assimilate young indigenous students into western Canadian culture. Indian agents would take children from their homes as young as two or three and send them to church-run boarding schools where they were punished for speaking their native languages or observing any indigenous traditions, routinely sexually and physically assaulted, and in some extreme instances subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization.

The last residential school closed in 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008.

Generations of Canada’s First Nations forgot who they were. Languages died out, sacred ceremonies were criminalized and suppressed. These double exposure portraits explore the trauma of some of the 80,000 living survivors who remain, and through accompanying interviews address the impact of intergenerational trauma, lateral violence, and document the slow path towards healing.