As China continues to urbanize, individuals from the countryside flood its cities in search of jobs that promise a more prosperous future. Consequently, the situation of the villagers who are left behind, and the preservation of these rural villages and their traditions, have become topics of global concern.

Sun Yunfan, Culture Editor for Asia Society's ChinaFile website, and Associate Director of Asia Society's Center on U.S.-China Relations Leah Thompson have compiled a photo essay of Instagram photos as part of their ongoing multimedia project, Bishan: Reinventing China's Emptying Countryside, funded by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. Over the next few months, the two will share notes from the field as they visit, report and film their ongoing project in rural Bishan village in China's Anhui province.

Asia Blog reached out to Sun Yunfan via email to learn about the genesis of her project and how it touches on so many issues that are central to present-day China's ongoing transformation.

In your own words, why should we be paying particular attention to the Bishan Project?

Experts estimate that by 2040 China will be 70 percent urban. This is a significant change for a population of over one billion, which, as recently as 1998, was 70 percent rural. And while hundreds of millions of people have been lifted from poverty, rapid urbanization has also uprooted traditions, severed family ties, degraded the environment, overburdened urban infrastructure and caused social alienation and growing inequality.

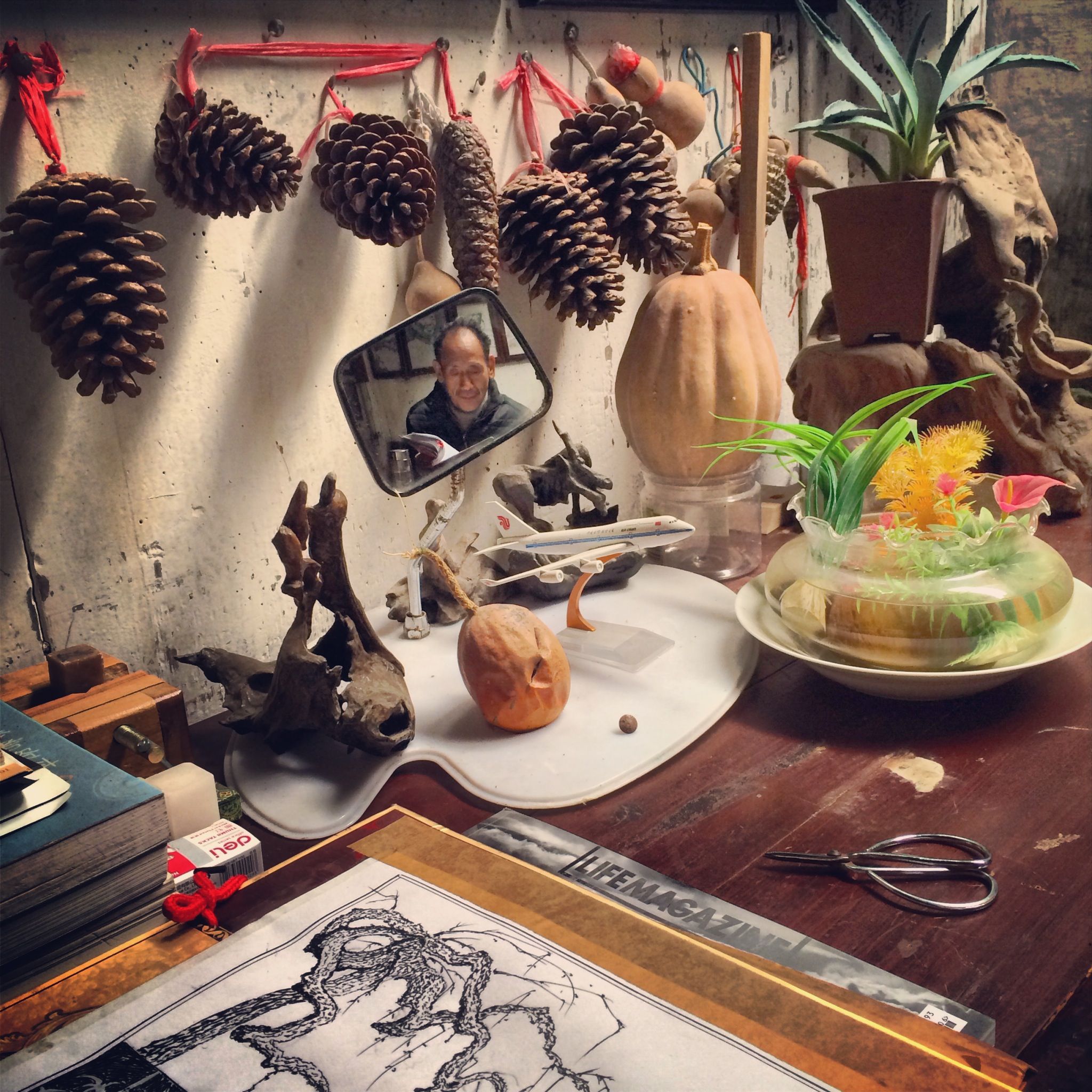

At the same time, a back-to-the-land movement is emerging in China, led by urban intellectuals who are experimenting with alternative development models in the countryside. Ou Ning and Zuo Jing, two artists and creative entrepreneurs from Beijing, founded the Bishan Project in 2011. In two years, they organized two cultural festivals which gathered hundreds of domestic and international artists in Bishan, started two magazines — Bishan, which focuses on traditional crafts, and V-ECO, which focuses on ecological living — and convinced China's most beautiful bookstore to open a branch in an old ancestral hall in Bishan. With the Bishan Project's encouragement, several junior village officials jointly set up a Taobao store to help sell local grown produce online, and plan to start organic farming this coming Spring.

Beyond the immediate success or failure of the Bishan Project itself, its experiments could be exemplary for the rest of China.

Does the Chinese government seem interested in preserving historic villages like Bishan? Why or why not?

Bishan village with its many late Qing-dynasty vernacular houses might be considered a heritage village worth "preservation" in another province, but in Southern Anhui province, historic villages with more and better preserved heritage sites are so abundant that Bishan is actually deemed lacking in preservation value. Within its 10-mile radius, there are two UNESCO World Heritage villages and half a dozen other historic villages managed by government-owned tourist companies. But it is precisely because its lack of mass tourism attractions that the founders of the Bishan Project chose Bishan to explore alternative development models. Through the cultural festivals it has organized, the media attention it has drawn, and its own publications, the Bishan Project has brought a certain kind of social and cultural capital to Bishan.

Although the Yixian County government shut down one of the festivals organized by the Bishan Project in 2012 due to the heightened political atmosphere before the 18th Party Congress, overall, the local government, especially the Biyang township government, has been very supportive of the Bishan Project simply because it has put Bishan on the map. Many junior village officials in the county have worked as volunteers for the Bishan Project.

How is Instagram, or more specifically, photography, a useful lens in giving Western society a glimpse of contemporary rural life in China?

Instagram is an incredibly powerful and democratic tool for sharing images and interacting with an ever-expanding global mobile community. Not to mention that it is arguably the only Western-invented social media that is not banned in China. While almost all of the villagers I encountered in these two villages have a TV set in their living rooms and spend a lot of time watching programs that are almost exclusively about urban life, most of them do not own a camera and rarely have the opportunity to have their photos taken. In this sense, just seeing themselves and their surrounding environment being represented in images gives them a simple joy.

In 2013, Ren Yue, one of China's leading photography critics and founder of the photo-educational organization OFPIX, cleverly used Instagram in a project she founded with Mulan, an NGO dedicated to helping female migrant workers in Beijing. She gave donated used iPhones to female migrant workers, taught them how to use Instagram, and asked them to take photos and share them on Instagram when they travel back to their hometowns. Whoever is interested in getting a glimpse of contemporary rural life in China through the eyes of female migrant workers should follow these Instagram accounts: @mulanxilin, @mulanhuangling, @mulanhaiying, and @mulanchunfen.

How is the atmosphere in the Bishan village different now that there are fewer urban tourists? Are family members returning to the village for the festivities at this time?

The villages seemed to be especially quiet at this time of the year. All farming activities have stopped. There are fewer visitors coming from urban areas due to the cold weather (15˚-30˚F). Family members who work as migrant workers in urban areas across China will not return to the village until a week before the Spring Festival starts — this year on January 31. But there are plenty of activities the local villagers are busy doing: almost all households are preparing preserved daikon and fish, splitting and stacking up firewood, racing with time to raise their pigs as fat as possible before slaughtering for the coming Spring Festival, cleaning up the house, and planning farming in the spring.

The anecdotes that you have posted in your field notes really speak to the strength of the elderly in Bishan and their resilience. How do you see them spending their day-to-day lives and keeping their spirits up?

The elders in Bishan have a strong sense of duty. To a lot of them the only intolerable thing in life is leisure time. Many villagers in their 60s and 70s take care of their parents and grandchildren on a daily basis. Aside from their all-year-round farming work based on the lunar calendar, they also raise silkworms, pick tea leaves, and constantly look for small jobs in the county town or even start their own businesses. And this includes Ou Ning's mother, Chen Xueping. Since she moved to Bishan village in the summer of 2013, she has been complaining to Ou about having too much spare time. Eventually she fired the hired cook, took on cooking for the household as part of her "job," and started planting vegetables and raising nine chickens in the backyard.

Do you think the average Chinese person cares about preserving heritage sites such as Bishan? What are the realistic chances of this movement's gaining traction?

What I have observed is that this movement is gaining traction among some Chinese who care about the same issues that the Bishan Project is interested in: preserving local crafts and traditions, promoting organic farming, ecological living, and sustainable development, and nurturing intentional communities.

According to a map compiled by Zuo in 2013, there are 53 similar projects across China. As China continues to aggressively urbanize itself at the expense of its environment and tradition, efforts like the Bishan Project definitely have the potential to grow into a larger social movement that is comparable to the Arts and Crafts Movement, Back to the Land Movement, or Organic Movement in the West.