Throughout most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Canada sought to forcibly assimilate aboriginal youngsters by removing them from their homes and placing them in federally funded boarding schools that prohibited the expression of native traditions or languages. Known as Indian Residential Schools, the institutions, which were often administered by churches, provided neither proper education nor adequate nutrition, health care, or clothing, and many of the students who passed through the system—an estimated hundred and fifty thousand children from the First Nation, Inuit, and Métis peoples—suffered abuse. The country has in recent years begun to reckon with the consequences of its policy. A report released earlier this year by a Canadian Truth and Reconciliation Commission described what happened in the schools as “cultural genocide.”

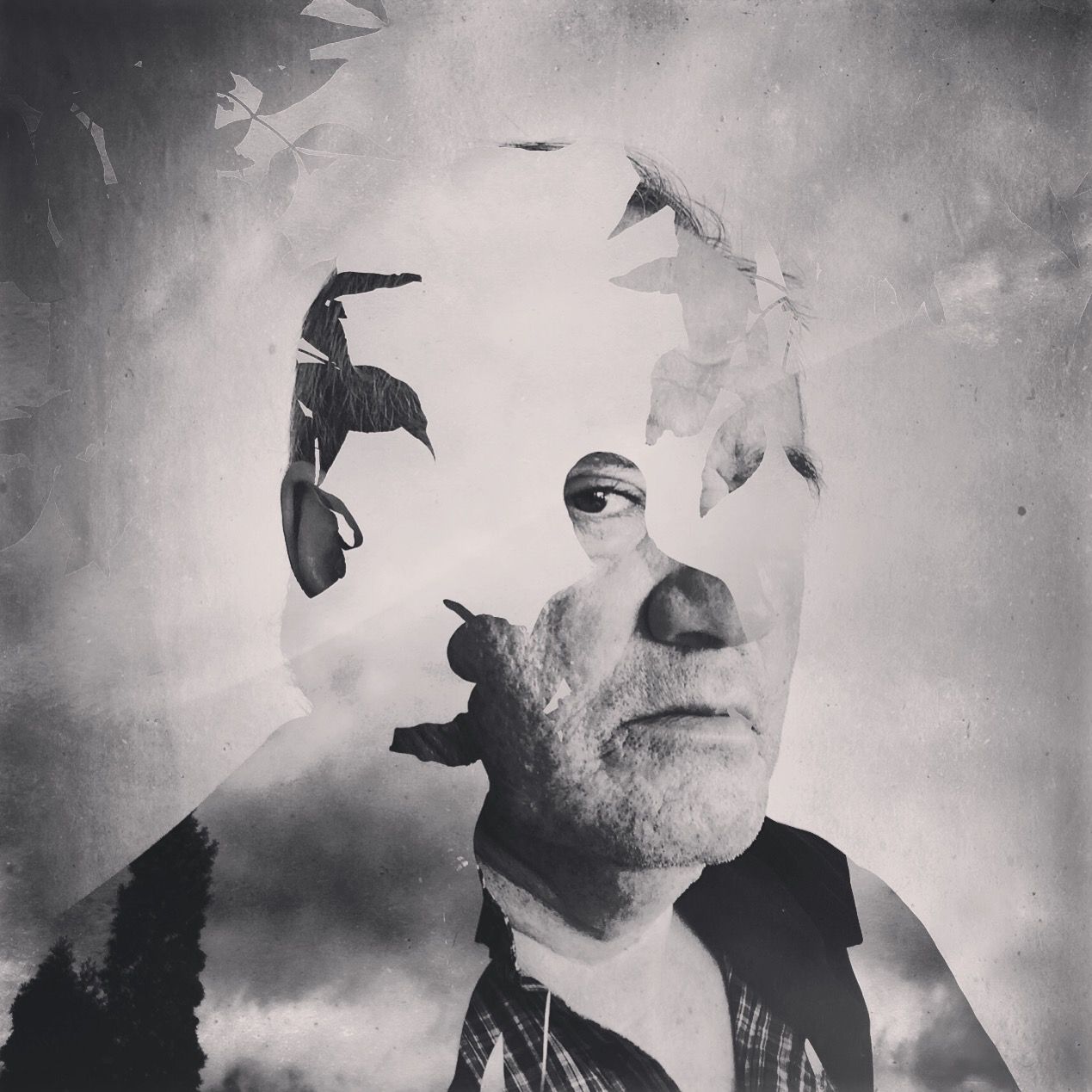

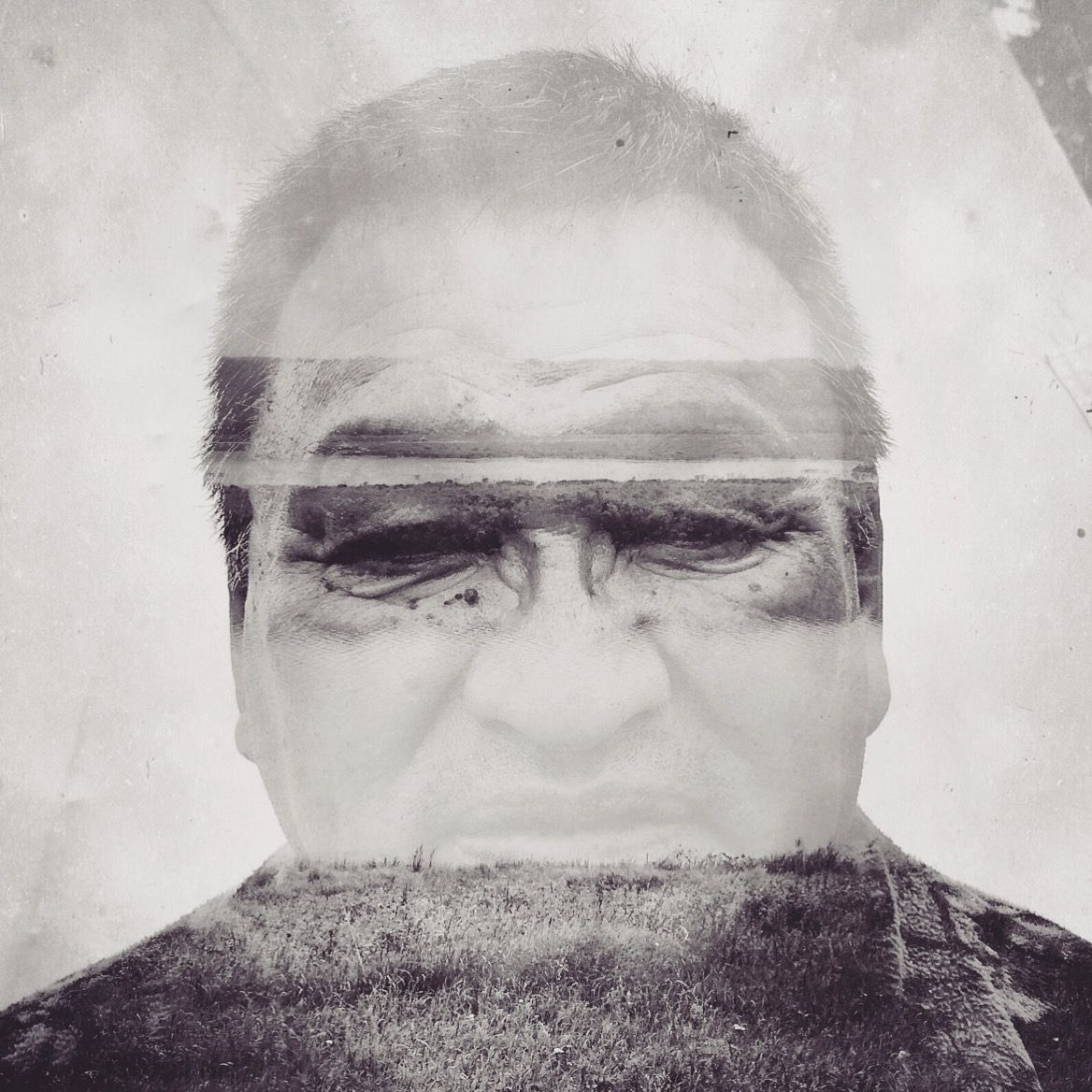

The American photographer Daniella Zalcman’s project “Signs of Your Identity” explores the traumatic legacy of the forced-assimilation schools. For two weeks this past summer, travelling on a Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting grant through the prairie province of Saskatchewan, where the last academy closed in 1996, Zalcman photographed forty-five survivors and recorded their stories, then created haunting double-exposure portraits overlaid with images of objects or places relevant to their experiences. The features of Rick Pelletier, who was severely beaten at a boarding school when he was seven years old, are almost completely erased by the writing on a tombstone. Valerie Ewenin, who lost her native language at boarding school, appears with her eyes and mouth covered by a broken window. “I was brought up believing in the nature ways, burning sweetgrass, speaking Cree,” she says. “And then I went to residential school and all that was taken away from me. And then later on I forgot it, too, and that was even worse.”