In his final sermon at Corpus Christi Catholic Church, Fr. Tony Anike stood on a fraying patch of carpet and preached an apocalyptic message to the parishioners scattered between the sanctuary’s crumbling walls.

“We don’t know what the future holds at Corpus Christi,” he began from his pulpit on Chicago’s South Side. His departure was a matter of routine reassignment, but bleaker changes, he predicted, seemed inevitable soon.

“Prepare yourselves, my friends,” he went on. “Because the next year will be interesting in this place.”

Though he didn’t admit it outright, the pastor’s warning essentially was that closure could be coming—and he’s not alone in sounding that alarm. Four predominantly Black Catholic parishes in the Archdiocese of Chicago have shuttered in the past two years, a number that the pandemic seems poised to expand.

In that same period, though, two Black Catholic Chicagoans have been elevated to the highest echelons of the faith: Archbishop Wilton Gregory, a freshly minted member of the College of Cardinals, and the 19th-century prelate Augustus Tolton, whom Pope Francis named in 2019 to the elite pre-sainthood rank of venerable. There’s good news and there’s bad news for Black Catholics in Chicago these days, and according to some of the faithful, the same establishment is responsible for both.

“What appears to be happening,” says Vanessa White, a Chicago-based scholar of Black Catholicism, “is that the institutional church is turning its back on the Black community.”

Church institutions have been vocal in recent months of their support for individual Black Catholics. Pope Francis named Archbishop Gregory a cardinal in December 2020, making him the first African American to earn the position and winning the “heartful congratulations” of Chicago’s own presiding Cardinal Blase Cupich, as issued in a statement following his nomination. Cupich’s officials have heaped similar praise on Fr. Tolton, befitting of both the history he could make and the logistical and financial stakes the archdiocese holds in promoting his sainthood cause.

“He would be a first,” says Bishop Joseph Perry, the Chicago cleric who chairs Tolton’s campaign.

The Catholic Church has never canonized an African American, and now that just two steps stand between him and sainthood, Tolton is better positioned than most to one day reach the peak—Pope Francis named just 47 holy men and women to the rank of venerati last year, from a pool of thousands of nominees.

Believed to be the first African-American priest ever ordained, Tolton established Chicago’s first Black parish just blocks from where Corpus Christi stands today—all after being born into slavery and, on the basis of race, rejected from nearly every American seminary.

“This offers a service or inspiration to the church,” Perry says, “and to any individual or group of people who are going through persecution.”

According to Kim Lymore, the trouble is simply that the church has done its fair share of persecuting.

Lymore, a colleague of White’s at the Catholic Theological Union and a staff member at the South Side’s St. Sabina Faith Community, occupies a unique position. Thanks partially to a long history of media savvy, St. Sabina has a thriving congregation and comfortably secure coffers—secure enough to employ Lymore as one of the only full-time Black lay ministers in the Archdiocese of Chicago. Though her own parish faces minimal risk of closure, the minister’s rank has allowed her to see the inner workings of the system behind other churches’ demise. Her verdict?

“It’s racist,” she says. “It’s a racist kind of struggle.”

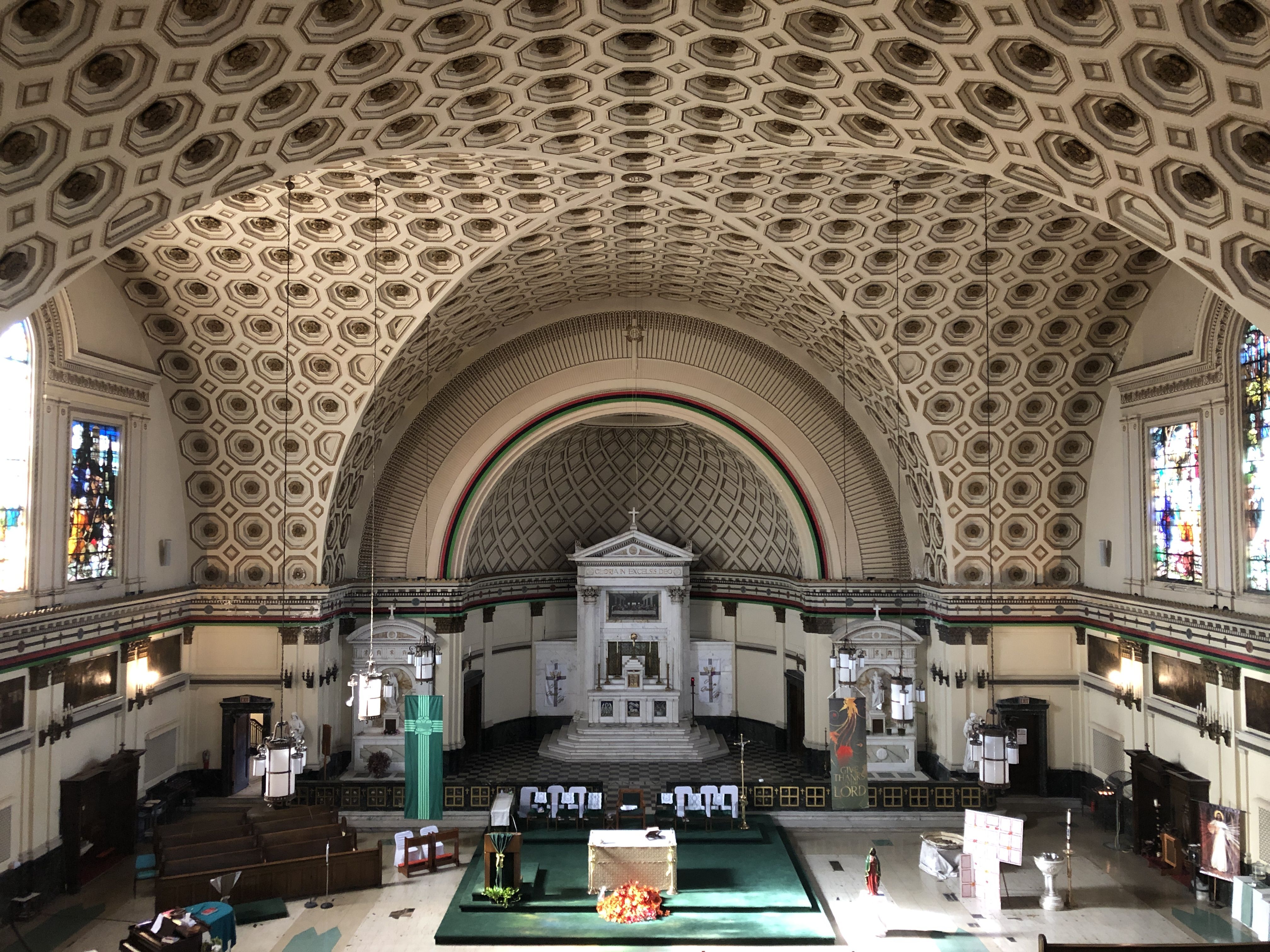

In Chicago, she explains, most majority-Black parishes occupy old church buildings that wealthy families vacated during the “white flight” era of the last century. While suburbanites built new facilities, Black Catholics were left with energy-inefficient sanctuaries that were long on history—Corpus Christi, for instance, was once the tallest building on Chicago’s South Side—but expensive to maintain.

That systemic disadvantage was compounded in 2018 when the archdiocese launched Renew My Church, an initiative designed to streamline the city’s parishes into a smaller, more active list. Through the program, every church in the archdiocese was assigned a geographically based grouping and set to be evaluated on factors, like mass attendance and financial self-sufficiency, on which Lymore says Black parishes are almost destined to fail. Add a pandemic, and a bad situation gets even worse.

“Just like it’s a major blow to small businesses, it’s been a major blow to the church,” she says. The hit to in-person attendance has caused an accompanying drop in collection-basket funds, which in turn has led Renew My Church leaders to accelerate the process of culling those parishes least likely to bounce back. In July 2020, the archdiocese announced it would complete the program in 2021, a full year earlier than anticipated, leaving thousands of Black Catholics vulnerable to parish mergers before they’ve even returned to their pandemic-ravaged pews.

Though Renew My Church extends only to the borders of Chicagoland, historian Matthew Cressler says that its injustices are universal within African-American Catholicism. Poor attendance, after all, isn’t endemic to Chicago, nor is it confined to the era of social distancing.

According to the Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study, only 39 percent of American Catholics attend church every week—and that was before Sunday mass posed a public health risk. In that challenging atmosphere, cash-strapped church officials must consider not just the number of active parishioners but how many potential mass-goers live near a parish, too. Since only 5 percent of African Americans identify as Catholic, majority-Black areas like the South Side are prime targets for cuts and closures.

“What increasingly happens is that the Church or the dioceses make arguments that, ‘Well, we’re not going to invest Catholic money into non-Catholic communities,'” says Cressler, the author of Authentically Black and Truly Catholic: The Rise of Black Catholicism in the Great Migration. “Which is a way of saying that we’ll subsidize the creation of new, suburban, overwhelmingly white Catholic populations, and we will be forced to close the Corpus Christis of the world.”

That a diocese would promote the sainthood of a Black Catholic while carrying out such disenfranchisement, he adds, is hardly a coincidence.

“Canonization causes often say more about the people promoting them than about the saints themselves,” he explains.

In Cressler’s view, a saint represents a community’s hopes for itself more than its everyday reality—and, through that lens, a Saint Tolton, like a Cardinal Gregory, would make a perfect symbol for the diverse but segregated Archdiocese of Chicago. His canonization may not be an “endorsement,” as Bishop Perry has put it, of any racial harmony already achieved in the city, but it would represent an inclusive aspiration. And for some Black Catholics, that carries its own form of power.

“It’s great to know somebody who’s become a cardinal,” says Lymore. Proximity to a figure who occupies one of the dozen highest-ranking positions in the American Catholic clergy can spark genuine pride, she explains, and for the many Chicagoans who worked or worshipped alongside him in his years of hometown ministry, it doesn’t get much more proximate than the man now known as America’s first Black cardinal. “It’s sad that it took so long, but it’s great that it’s finally going to happen.”

Vanessa White feels similarly about Venerable Tolton.

“If he became a saint, yes, of course, there would be jubilation among Black Catholics,” she says. But the community’s problems—from crumbling infrastructure to closure threats—would remain.

Back at Corpus Christi, that means a departing pastor with little ability to preach good news.

“Christians are not people who are swayed by the fact that people are leaving,” said Fr. Anike in his final sermon. “Christians are the ones who stay to the end.”

He was just unsure, at Corpus Christi, when the end might be.