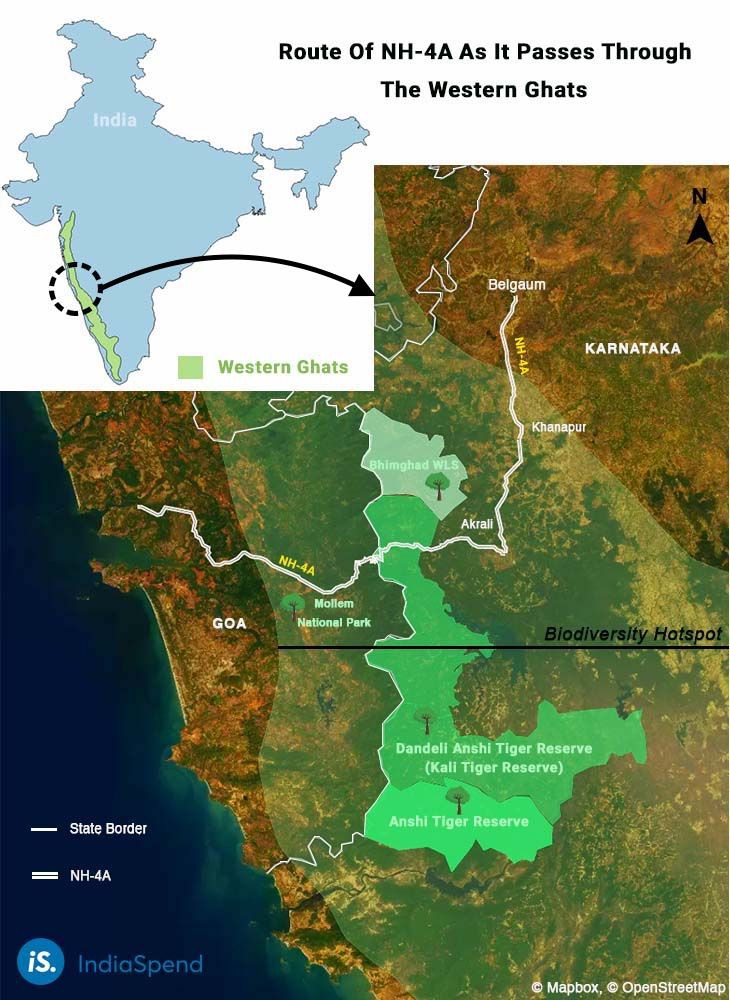

Belgaum & Bengaluru: The three-hour long drive along National Highway (NH)-4A from Belgaum in Karnataka to Goa starts on a wide, traffic-free, four-lane highway. About an hour later, the road begins to narrow and the surroundings change. The canopy grows so thick that the harsh daylight turns gentle by the time it reaches the road. The NH-4A is now a two-lane stretch for which the word ‘highway’ doesn’t quite seem right.

This is because before entering Goa, the road passes through the Western Ghats, a 1,600-km mountain range that stretches from Gujarat in western India to Tamil Nadu in the south. The range is a global biodiversity hotspot* and a UNESCO world heritage site. This hotspot covers less than 6% of India’s land area but hosts nearly one-third of the country’s plants and animals, including 325 endangered species. The Western Ghats is home to nearly 30% of the world’s Asian elephant and 17% of the planet's tiger populations. The mountains are also the origin points for multiple rivers, including the Godavari, Kaveri and Krishna.

The Western Ghats is an ecologically fragile region. India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has granted environment clearances (EC)* to 76 projects in the Western Ghats since July 2014, according to an IndiaSpend analysis of proposed projects granted approvals or expedited from July 2014 to March 2020. Of the 76 approved projects, one is within a Protected Area (PA)* [Karnala Sanctuary in Panvel, Maharashtra] and 18 are within 10 km of a PA.

This is the story of the widening of NH-4A. In this story, we will also explore how seemingly small-scale disturbances in ecologically sensitive areas are likely to have a compounding impact on wildlife, endanger public health and exacerbate natural disasters.

While PAs help retain forests, road projects such as NH-4A, and human activities have the opposite effect. “The chances of forest loss 4 km away from a road is 21% lower compared to the chances of forest loss closer to the road,” said Meghna Krishnadas, project scientist at Laboratory for Conservation of Endangered Species at Hyderabad’s Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, based on a 2018 study that she was a part of in the Western Ghats. In other words, proximity to a road makes a forest vulnerable to loss.

This is not just the story of NH-4A alone. It is one that gets repeated project after project in the name of development, chipping away at this ecologically fragile region. This is the second of our multi-part, data-driven series, Environment Undone, which explores the environmental, ecological and human cost of India’s chosen path of development. You can read part one here.

Rolling out an expansion

The 153-km NH-4A (also known as NH-748) connects the industrial town of Belgaum to Goa, a state with ports.

For the NH-4A widening, the administration in both the states--Karnataka and Goa--did not seek the required environment and other approvals, official documents that IndiaSpend pored over during the year-long investigation for this series show.

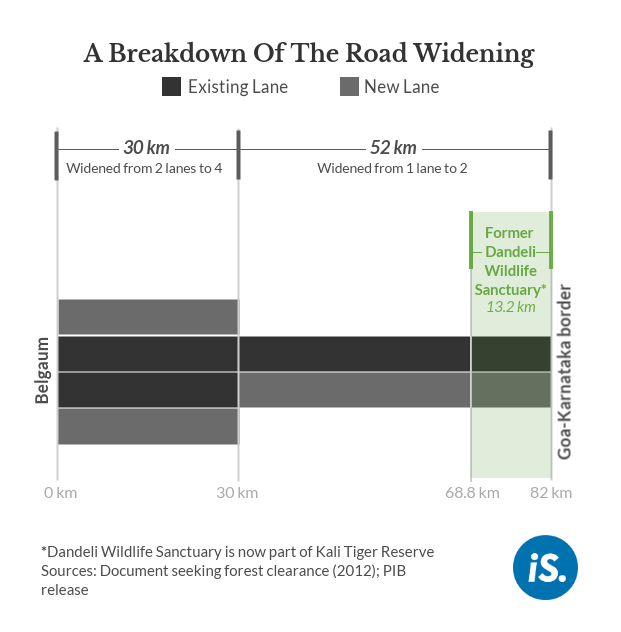

The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI), an agency under the Central Ministry of Road Transport and Highways (MoRTH), undertook the widening of 82 km of the 153-km highway on the Karnataka side at an estimated cost of Rs 1,395 crore in March 2018; almost the entire 82-km stretch passes through the Western Ghats.

The NHAI estimates that nearly 22,000 trees were cut along the 82-km road in October 2018 even as local activists have claimed that the number of hacked trees stands at over 100,000. Some of the chopped trees stood on land that was earlier a part of the 475-sq km Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary, a PA.

IndiaSpend reached out to the principal secretary of forests for Karnataka Smita Bijjur and to MoEFCC’s additional secretary incharge of biodiversity BV Umadevi for inputs and comment. Both Bijjur and Umadevi did not respond despite repeated calls and emails over months. We will update this report if and when they respond.

Globally, PAs are seen as the cornerstone of conservation as they are able to maintain biodiversity within their boundaries.

Roads, on the other hand, are valuable in forging connectivity. “A wider road will be better for us. Besides, it will reduce the chances of accidents,” said Majhirao Jadhav, 30, a resident of Kinaya village on the outskirts of Belgaum.

They also have economic value. “The road sector, especially highways, are important because they enable the growth of logistics--the freight logistics sector--which brings in a lot of jobs and a lot of economic wealth to the area the road passes through,” said Sanjay Gupta, professor of transport planning at the School of Planning and Architecture (SPA), New Delhi.

Balancing economic needs with environmental concerns is a tightrope walk. Environment minister Prakash Javadekar has spoken about how development and the environment must go hand-in-hand. He granted wildlife clearances to dozens of projects within a fortnight in the early days of the COVID-19-induced, national lockdown.

Javadekar chaired a meeting of the National Board for Wildlife (NBWL), via video conference, on the first day of the lockdown on March 25, 2020, to clear over 40 projects. He chaired another NBWL meeting on April 7, 2020, and granted clearances to projects in 11 states, the details of which he tweeted. The approved projects include building highways, stone mining projects and other projects that involve diversion of land from wildlife sanctuaries (WLS).

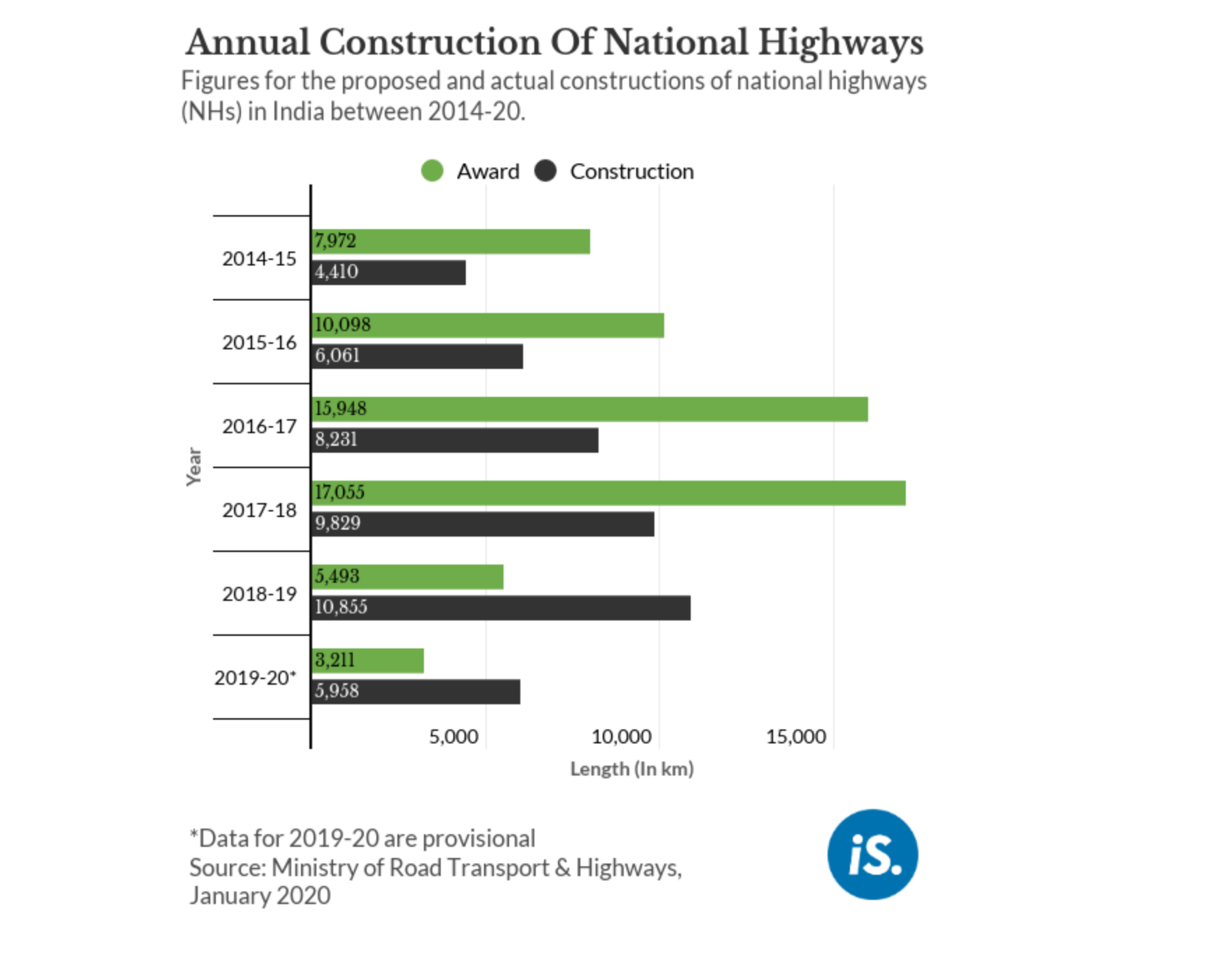

Economic arteries

Spanning over 5.89 million km, India has one of the largest road networks in the world. The length of India’s national highways increased from 91,287 km in April 2014 to 132,500 km in December 2019, according to the latest data from the MoRTH released in January 2020. The Centre’s spending on national highways increased over three times from Rs 33,745 crore in 2013-14 to Rs 1.37 lakh crore in 2018-19. This road network transports an estimated 64.5% of all goods in the country and 90% of India’s total passenger traffic.

The National Democratic Alliance (NDA)-led government announced plans earlier this year to invest Rs 100 lakh crore in infrastructure projects for five years till 2024-25. This will include development of 2,500 km access control highways* that are designed for high-speed traffic, 9,000 km of economic corridors*, 2,000 km of coastal and land port roads and 2,000 km of strategic highways*, the government said in the 2020-21 budget.

Infrastructure investments are needed, according to economists, to promote growth and economic activity. “History shows us that only those countries that made a substantial investment in public infrastructure [such as roads and power projects] have moved ahead in the league tables. China is the most recent example,” R Nagaraj, an economist at the Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, told IndiaSpend.

Minister of Road Transport and Highways Nitin Gadkari laid the foundation stone for NH-4A’s widening in Karnataka on March 19, 2018. The project was part of an investment of Rs 1.45 lakh crore for the development of NHs in Karnataka over a period of two years until 2020. At the foundation laying event, Gadkari, who is also the Minister of Shipping, additionally announced 48 new port projects and stressed on improving port connectivity through roads under the Sagarmala project.

Days later, the NHAI handed over contracts worth Rs 1,395 crore for the NH-4A road widening in Karnataka to two private companies, Ashoka Concessions Limited and Dilip Buildcon Limited. While awarding the contracts, NHAI said it was being done to connect “a major city in the state of Karnataka, and Panaji, the state capital of Goa, a major port and an international tourist destination”.

This is the kind of project that India, with a population of 1.3 billion and demand for growth, needs, say transport experts. “There are many studies to show that if you open up areas for roads, there is always economic development around them,” said SPA’s professor Gupta.

Dodging approvals?

Under the NH-4A widening project, 30 km of the 82-km road starting at Belgaum was proposed to be widened from a two-lane road to a four-lane one. The next 52-km stretch that cuts through the Western Ghats was proposed to be widened from one-lane to two lanes. The last 13.2 km of this 52-km section passes through what was formerly the Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary (475 sq km) and is now the Kali Tiger Reserve. The road then proceeds towards Goa.

Spotting a deer, while driving through this last 13.2 km section of the road, or even a leopard, is not uncommon. There’s a cacophony of sounds--wild animals, rare birds and then, some insects. It takes a trained ear to distinguish the calls and identify the species it is coming from. This is a road through a jungle at its best. Motorists here narrate encounters with tigers, sprawled in the middle of the road after sundown, just as one would at one’s home.

Given that NH-4A passes through the Western Ghats, the widening project required environment, forest and wildlife clearances. The NH-4A widening had been undertaken earlier too, and the Karnataka government had sought a forest clearance* for the same in 2012. The widening work at the time had stalled.

In 2016, the Gadkari-led MoRTH had taken measures to expedite “languishing” road projects. This included eliminating the requirement for an EC for roads upto 100 km long.

In 2018, the NHAI proceeded with the project without seeking any fresh clearance after the 2016 tweaking of rules. Similarly, the government of Goa took into account the 69.07-km section from the Goa-Karnataka border to Panaji, in its Environment Impact Assessment* report made for the Goa side of the road in July 2018; it neither sought a wildlife clearance*, nor an EC, for the widening project.

To those familiar with the region, this was a travesty. “We argued in court that the EC cannot be done away with,” said 69-year-old Suresh Heblikar who is one of the three petitioners to have filed a public interest litigation in the Karnataka High Court in January 2019 against the felling of trees to widen NH-4A in Karnataka. “They [NHAI] admitted that they neither had environment clearance nor a go-ahead from the Wildlife Board [of Karnataka].”

The Karnataka High Court (HC) stayed the felling of trees in October 2019. Work on the widening has since stopped. The HC later noted that since the road stretches for over 100 km across two states, “it cannot be said that widening is undertaken for the length which is less than 100 kilometers”.

“The trees were gone by the time the Court issued a stay. Certain stretches of the road may be left [for finishing work], but these are a few stretches,” Heblikar told IndiaSpend. The noted Kannada filmmaker, actor and environmentalist said he viewed the NH-4A widening project as a “blatant destruction of nature”.

IndiaSpend has reached out to NHAI chairman Sukhbir Singh Sandhu, and to the two companies, Ashoka Concessions and Dilip Buildcon, carrying out the road widening work for NH-4A in Karnataka, to ask about mitigation measures undertaken. We will update this report if and when they respond.

Bit by bit, the forest falls

Roughly 5% of India’s total land area is “protected”, i.e. it enjoys special legal protection against human activity. Taking this protection away requires green clearances, and they are not hard to come by, as we explored in the first part in this series. Scientists have now pointed out that in India, the density of linear intrusions* within PAs is the same as it is outside the PAs. Nearly 70% of PAs in the country have linear intrusions, such as roads or power transmission lines, passing through them, the scientists stated in a study published in the journal Land Use Policy in April 2020.

Linear intrusions that pass through PAs--and NH-4A qualifies as one in both Karnataka where it goes through Kali Tiger Reserve, and Goa where it penetrates the Bhagwan Mahaveer Sanctuary and Mollem National Park--not only lead to forest fragmentation* but also endanger wildlife, as we will explore later in this report.

Fundamentally, roads create an opening in a forest. “And that [the opening] has a mushrooming effect* wherein there is not just traffic but inflow of people and outflow of wild meat to markets and viruses [causing diseases] such as COVID-19,” said Krithi Karanth of Bengaluru’s Centre for Wildlife Studies (CWS). Karanth was one of the scientists involved in the study on forest fragmentation due to linear intrusions.

The fragmentation and the consequent mushrooming effect that Karanth and fellow scientists are now warning about was flagged nearly a decade ago by ecologist-scientist Madhav Gadgil. In 2011, Gadgil chaired the Western Ghats Ecology Expert Panel, better known as the Gadgil Commission, which recommended that there be no changes in land-use pattern in the Western Ghats. The panel’s report warned of ecological disasters and sought an absolute ban on mining and large dams there.

“The Gadgil report wanted to identify certain areas as inviolable,” said Nandan Nawn, an economist who specialises in environment and development at TERI School of Advanced Studies (TERI SAS), New Delhi.

None of the six Western Ghats states fully imbibed the recommendations of the Gadgil report.

Indiscriminate mining and infrastructure activities continued unabated throughout the Western Ghats states. Most of the deaths and devastation during the 2018 Kerala flood, described as a once-in-a-lifetime event, were due to landslides in the areas where mining and quarrying are rampant, an IndiaSpend analysis in August 2018 had revealed. The continued destruction of the Western Ghats was again attributed for the large number of landslides that followed the 2019 floods in Karnataka’s Chikkamagaluru district and large parts of Kerala.

Hotbed of zoonotic diseases, Ecosystem services

“The forests [of the Western Ghats] provide several critical ecosystem services,” Mahesh Sankaran, an ecosystem and community ecologist at the National Centre for Biological Sciences (NCBS), Bengaluru, told IndiaSpend. “They are important for hydrological services, provisioning services and carbon sequestration* services, amongst others.”

Public health fallouts of infrastructure projects in the Western Ghats are also beginning to become visible. PAs are hotbeds of zoonotic pathogens*, and deforestation is an important factor that contributes to increased interactions at wildlife-human interface, according to studies.

“Large-scale economic projects such as linear infrastructure, mines, and hydropower projects in natural habitats can disrupt ecosystems, causing conditions that can promote the emergence of zoonotic disease,” said Abi Tamim Vanak, a senior fellow at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), and a DBT/Wellcome Trust India Alliance fellow.

The spread of Kyasanur forest disease (KFD), a tick-borne disease in Western Ghats, that is believed to jump to humans from affected monkeys, is a case in point. The disease is known to cause headache, fever, chills, severe muscle pain and bleeding in humans. KFD’s emergence was first recorded in the late 1950s in Shimoga district in Karnataka’s Western Ghats region. It has since spread to other states, including Kerala and Tamil Nadu with stray cases being recorded as far as in Gujarat. Between 400-500 cases of KFD are reported in the Western Ghats on average annually, and of these between 3-5% turn fatal, according to the United States’ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which monitors global disease outbreaks.

“Changes in the land use in the Western Ghats, particularly, the mix of moist evergreen forests with plantations, and the increased presence of human activity and livestock, results in higher incidence of KFD,” Vanak told IndiaSpend.

Number crunching

Healthy forests and habitats in the Western Ghats perform ecosystem services that are critical but hard to translate into monetary value. “The economic value of ecosystems are difficult to capture, let alone compute,” said Nawn of TERI SAS. “Non-market valuations [ways of valuing goods that cannot be traded directly, such as air or wildlife] are yet to receive acceptance beyond a section of academia.”

For instance, how does one translate the joy forests bring to the tourists, the trekkers or to those to seek out green places to meditate? These are the kinds of ecosystem services scientists like Sankaran said are hard to put a number to.

A forest clearance approval for a proposed project entails the project proponent* having to pay a certain amount for compensatory afforestation activities and plant trees elsewhere even though plantations do not offer the same benefits that an ecosystem does, as IndiaSpend reported in June 2019.

The monetary value attached to forest clearance approval is very low, said Jagadish Krishnaswamy, senior fellow at the ATREE and a coordinating lead author on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on climate change and land degradation. “We cannot have sustainable development by inflicting irreparable loss to ecosystems.”

In the case of NH-4A widening project, understanding the value of the forests is further compounded by doubts that have been raised about the number of trees that have been cut to make space for the road widening.

“The NHAI admitted in an affidavit to the court that 22,000 trees were felled for the road widening and that there will be no more felling,” said Prince Isac, Bengaluru-based environment lawyer representing Heblikar.

“On average, there are around 1,000 trees in a km-long stretch in this [between Belgaum and Goa-Karnataka border] area,” said Lingaraj Jagajampi, the 38-year-old joint secretary of Belgaum-based NGO Paryavarni. “If trees have been cut on both sides of an 82-km long road, how can the number [of trees that the NHAI estimates it has cut] be just 22,000?”

Jagajampi claimed that patches far away from NH-4A have witnessed loss of trees in the months following the NHAI’s clearance of 22,000 trees in October 2018. IndiaSpend tried to assess his claim independently and reached out to remote sensing expert Raj Bhagat Palanichamy for this. Palanichamy examined satellite images for the area for three months, December 2018, January 2019 and February 2019, and found that apart from the visible impact from the widening of NH-4A, forests along the road were also thinning over the period of time. This appears to be in line with the findings of Krishnadas’ study on forest loss as a result of road proximity.

Collateral damage: invasives, inbreeding, roadkills

“We have a lot of endemic species across all groups [taxonomic*] that are not found elsewhere, particularly amphibians* and plant species. That is reason enough to conserve it (Western Ghats),” said Sankaran of NCBS. Animals such as the Nilgiri tahr (Hemitragus hylocrius) and the lion-tailed macaque (Macaca silenus) and plants such as several climbers, medicinal and aromatic plants (Acronychia pedunculata, Chloroxylon swietenia) are native to the region.

The disturbance that roads create in the vegetation allows invasive species* to take hold and thrive. “Most invasive species do well in disturbed habitats because they are good colonisers*,” said Sankaran, adding that these species might not have had the chance to thrive had the linear intrusion (road or railway track) not been built. “Once they [invasives] come in, they outcompete the natives.”

Road projects through tropical forests*, such as the one in the Western Ghats, imperil the region’s wildlife and birdlife. Roads fragment both animal populations and plants. “Animals tend to avoid roads,” Sankaran told IndiaSpend. “When you fragment smaller animal populations, there is a chance of them going extinct purely due to inbreeding*.”

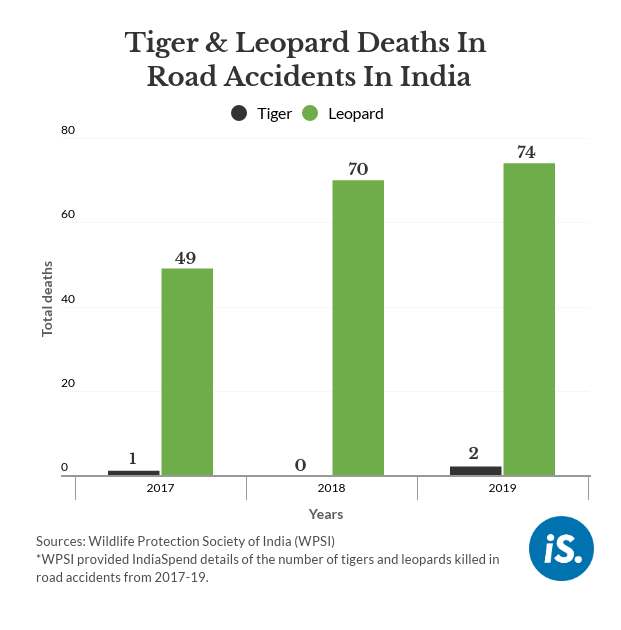

Animals are prey to becoming roadkills. While there is no publicly available record of animals dying in road accidents in the Western Ghats, we know that at least 161 wild animals died in road and rail accidents across India in 2018, according to data from the Wildlife Protection Society of India. The Society provided data for roadkills they have recorded for two animals: tigers and leopards.

Birds too are unable to escape the damage. “There is a lot of blasting, leveling and earth-moving work [when a road is widened],” said Raman Kumar, a Dehradun-based researcher with Nature Science Initiative who studies the impact of human activities on birds. “Apart from creating physical disturbance, road construction in mountains for instance also creates a lot of debris that is often dumped into nearby streams and rivers, which can destroy riverine* habitat and pollute the water upon which birds and other animals depend.”

The concerned ministry, while granting environment clearances to proposed projects, should therefore think hard about how roads disrupt ecological connectivity and threaten plant and animal diversity, said ATREE’s Krishnaswamy.

Protected Area predicament

The PA through which NH-4A passes in Karnataka itself has been in a flux since 2015, IndiaSpend found during the reporting for this article. The initial 2012 forest clearance granted for widening NH-4A states that the highway passes through the Dandeli Wildlife Sanctuary (WLS). Dandeli WLS was merged with Anshi National Park in 2015 to form the Kali Tiger Reserve.

The MoEFCC recommends an eco-sensitive zone* (ESZ) of up to 10 km around PAs in order to restrict human activity around it. “The purpose [of declaring ESZ] is to secure areas around the national parks and sanctuaries, including corridors,” said Praveen Bhargav, managing trustee of Wildlife First and a former NBWL member (2007-10). “This will ensure that they have some cushion, so that development projects do not intrude, particularly the nasty ones, right up to the boundary of the national park or sanctuary.”

In 2015, Karnataka told the MoEFCC that they wished to propose an area of 1,201 sq km as an ESZ around the Kali Tiger Reserve. Two years later, the state shrunk this proposed protected cover by 75% to 312.5 sq km citing “public demand”.

The rules and clearances needed for project approvals differ depending on whether a project falls within a PA, within an ESZ or outside it. Reducing the ESZ leaves room for projects closer to a PA.

Need for creative solutions

Professor Gupta of SPA said it is important to balance environmental concerns with the growth needs of the country, and feels that the numerous processes that are in place weed out projects that could cause massive damage to the environment.

When there is a tug between balancing these needs, conservationists propose looking for solutions that tread a middle path. One option might be to build a longer road that would go around the PA rather than through it or tunnel under it. This is the most viable alternative [to road projects that penetrate PAs], according to CWS’ Karanth.

If a road must be built through a PA for unavoidable reasons, then she advocates for mitigation measures to be adopted, because animals have been found to use such funneling mechanisms if the right kind of pathways are created. “There are enough examples from the US, Canada and Australia where authorities have built overpasses, underpasses and tunnels [in order to facilitate wildlife movement where roads interfere with their natural habitat],” said Karanth.

On a national scale, “Identification and designation of ecologically sensitive areas has to be an informed process involving political decision making,” said Nawn of TERI SAS. He further pointed out that there is currently no space where policy, regulation and scientific evidence intersect to aid conservation on balanced development. Scientists will have to make a case for conservation and quantify it better, policymakers will have to find a way to ensure that the value of the ecosystem services is taken into account and laws will have to be adequately stringent to prove as deterrents.

ATREE’s Krishnaswamy would like to see the MoEFCC to champion the environment India’s ecological security. “The ministry [MoEFCC] should be focusing on stewardship of environmental protection and ecological concerns. It should be less of a project-sanctioning agency,” he said.

This is the second in our multi-part series that explores the environmental, ecological and human cost of India’s chosen path of development. You can read the first part here.

Data analysis by Pankhuri Kumar and with inputs from Tish Sanghera. Graphics by Jameela Ahmed and Vishal Bhargav. Editing by Marisha Karwa.