To hear Mireille tell it, her romance started off like any other. Mireille, then 28 and in graduate school in the Midwest, gravitated to David, a tall, dark-haired fellow grad student at a party in October 2013. In early 2014, the two began dating. “Things were really perfect at first,” she says. “I remember one time I was just exhausted from a long day, and he came to my place with Chipotle and gave me a massage and read poetry to me. It was incredible.”

It didn’t stay incredible. What happened next wasn’t typical of a healthy partnership at all.

One evening that spring, Mireille says, she came home to find David sulking. He’d snooped through her laptop and found evidence of a brief relationship she’d had in late 2013. Though she explained that man was totally out of her life, “this topic came up over and over … ” Mireille recalls of David’s jealousy. Soon, periodic interrogations escalated into insults (“Whore. Evil. Bitch. Nasty slut,” she lists). Once, she says, “The neighbors called the cops because he … started yelling and grabbing my wrists and throwing me around.” Although he often begged for forgiveness, no real changes occurred.

Finally, “I just couldn’t take it anymore and took a knife to my wrist,” she says. “I said something to the effect of, look, HERE is your damn proof that I’m being honest with you.” It didn’t work. By December, the abuse was unrelenting. When David — who refused to be interviewed for this article – hit her in the face, Mireille had had enough. She left him, and, convinced he was stalking her, secured a protective order from a court.

Interventions

If that situation is intense, it’s also common. In Illinois, over 100,000 domestic violence incidents are reported annually. Nearly 60 percent are intimate partner violence, abuse between people who have (or have had) a romantic relationship.

Mireille doesn’t fit the image of a victim. She’s accomplished — her university website lists a string of awards she’s won. She’d been the economically stable partner (she says David “only bought groceries”). Her move for self-preservation was unusually swift too: She’d used the court system to protect herself the first or second time David had struck her, leaving him then. “A very small minority” move as quickly as Mireille did, Chicago Domestic Violence Legal Clinic representative Margaret Duval says.

Without calls for help, support organizations find themselves with limited tools for intervention. Stephanie Love-Patterson, executive director of Chicago’s Connections for Abused Women and Their Children, says her organization often contacts victims when they’re inpatients in trauma wards. “They’re at the very end stages of their relationships,” she says. A 2010 Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority study of an emergency shelter reported many women arrived only after abuse had become life-threatening.

Other services in Illinois focus almost solely on a relationship’s aftermath. A project announced in October 2014 in Chicago, for instance, enhances legal advocacy for survivors seeking restraining orders against their abusers. Another recent effort packaged counseling, legal support and practical assistance into a “one-stop shop” in some Illinois counties. But both programs focus on prosecuting abusers — something Duval says women often attempt only after a relationship “has been over for a while.”

In a culture that so often asks “why didn’t she just leave him?,” a logical question goes unasked. Why can’t interventions come before trauma wards or courts are necessary — or before a victim starts cutting herself in desperation, like Mireille did?

Violence as an Infectious Disease

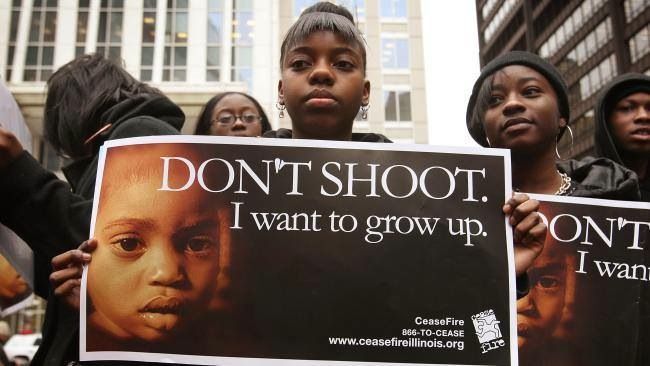

The city that patiently waits for people to assault their romantic partners does not wait for them to commit other types of violence. Fifteen years ago, Chicago’s high rate of lethal shootings prompted an innovation: violence interruption. The program, called Cure Violence (which started as CeaseFire), involves figuring out who is likely to commit a violent act in the near future, and then sending community health workers (“interrupters”) to contact prospective perpetrators, talk them out of committing violence and resolve their conflicts.

Focused on low-income, high-crime neighborhoods, the program employs ex-gang members or reformed convicts — people who understand gang culture and the temptation to do violence. This emphasis on the credible messenger is one of the effort’s most important ideas.

Another important factor involves labeling violence an infectious disease. Cure Violence founder Gary Slutkin, an infectious disease doctor who previously fought epidemics in Africa, says a single homicide can trigger multiple retaliations in an ever-widening circle — just as the first patient in a cholera outbreak infects other people, who then infect still more.

On the streets, this is no statistical abstraction. Violence interrupters operate in geographical areas defined by their high prevalence of gun violence. When violence is likely to occur, they use relationships with people who are likely to perpetrate violence, and their family, friends or fellow gang members, to help prevent outbursts or retaliations. They also follow up with high-risk people, offering steady support for permanent positive change. For both tasks, CeaseFire operates by being deeply integrated into communities that suffer high rates of gun violence. Autry Phillips, who manages a CeaseFire site in Chicago’s Auburn Gresham neighborhood, sums up the technique: “You have to show up, and show up, and show up.”

Showing up works. A 2014 evaluation found the program had reduced homicides by 31.4 percent in Chicago in the previous year. Since the late 1990s, it’s played a role in Chicago’s murder rate falling by half. As a result, CeaseFire has been exported to seven countries, including South Africa.

A Rape Capital

Hanover Park, near Cape Town, is a rundown place, crowded with tenement blocks, tin shacks and deep poverty. The area replicates a pervasive South African phenomenon: near-obsession with security. (Stand outside the fortress-like healthcare center, for instance, and security guards will insist you retreat behind the barbed wire-wreathed metal gate.) Here, paranoia feels justified. The country as a whole has a homicide rate that’s six times higher than the U.S. murder rate, and this community ranks among the worst affected. Chicago’s West and South sides — CeaseFire target areas where an ordinary Friday night might end with 16 people shot — seem calm by comparison.

Nonetheless, Hanover Park has enjoyed success using Chicago’s method. Since the program’s start in 2013, gunshot wound patients arriving at the Hanover Park Healthcare Centre have decreased from 129 (in 2012) to 59 (in 2014) — a fall of more than half.

The model’s portability makes sense. Cape Town and Chicago are 8,500 miles apart, but both have a history of segregation, a culture that values gun ownership and a high homicide rate. In each city, stark socioeconomic inequalities concentrate murders in just a few gang-ridden areas.

The cities are alike in another way: Their CeaseFire programs don’t address intimate partner violence, despite its high prevalence in both. In Chicago, Slutkin acknowledges the gap. “Women have been protected and saved” by other programs, he says, but “the focus of other people working in this area is not enough.” In Cape Town, site director Craven Engel agrees: “No one is really focused on this issue.”

Yet they do differ — if only because South Africa is the putative “rape capital of the world.” In the U.S., about one in five women will experience rape; in South Africa, the figure is over half. Four in 10 South African men admit to forcing a woman into sexual contact against her will. (“Eighty percent of these guys are perpetrators [of sexual violence],” Engel estimates about the gang members his interrupters assist.) Can interrupters show up for a very different kind of violence?

Silent Survivors

Radhika Sharma shakes her head at the question.

Sharma works at Apna Ghar, an agency in Chicago, “mostly working with people who have survived violence and their children, and helping them to cope.” The organization focuses on immigrant groups (Apna Ghar is Hindi for “our home”), but Sharma says most abuse the agency addresses is not culturally specific. She’s skeptical, however, that CeaseFire’s method could be adapted from one type of violence to another.

Sharma says she used to manage a CeaseFire program in Chicago’s Albany Park. “A lot of that is predictable,” she says, referring to shootings. “It’s much more difficult to predict that in an intimate partner situation.”

It’s not entirely simple for gun violence. “How did you know about that?” Stephen Colbert asked violence interrupter Ameena Matthews about violent incidents on the “Colbert Report” in 2012. “Is there like a Bat Signal that goes up?”

In Hanover Park, the Bat Signal is data. There, CeaseFire keeps a “war room,” where a wall displays neighborhood maps. The interrupters have divided the area into beats, defined by the gangs that control each street and their interrupters’ credibility with them. In another room, they’ve installed the ShotSpotter, software that registers the locations of gunshots by picking up sounds with strategically placed sensors. They use the precise latitudes and longitudes — easy to map onto the neighborhood they all know well — to understand where shots are being fired. There’s a database of every violent incident interrupters have worked, coded by weapons used and outcome (injury, death, neither), and a file of anonymized data on every individual on whom they’ve intervened.

The upshot is a fastidious, comprehensive picture of gang violence in the area. But the approach works only because the area is small and clearly defined: Hanover Park, ringed on all sides by major roads and small enough to walk across in a few minutes, contains 56,000 people, of whom CeaseFire estimates 1,600 are gang members. CeaseFire estimates that 18 percent of the 1,600 gang members — 300 people — are likely to be perpetrators of gun violence, and about 10 percent — 160 people — have contact with CeaseFire. That’s enough, they say, to reduce homicides in the two years the group has been working, despite the intimacy of just five interrupters and a handful of outreach workers. (The small size, of course, also means that every single interaction can have an outsize impact. Site coordinator Raymond Swartz recalls that in November 2014, a group from the nearby area of Manenberg “came to Hanover Park and shot and killed three high-risk youths, [which] triggered an all-out war.” The fight resulted in 17 homicides over the course of three weeks.)

On the South Side of Chicago, Autry Phillips and his team work with a population about the same size as Hanover Park. They rely on calls from CeaseFire workers employed at nearby Trinity Hospital, sometimes glean information from police, and — after 16 years on the job (and often a lifetime of residence) in the communities they serve — also rely on their own intuition.

CeaseFire’s key innovation, however, lies not in data or intuition, but rather in recognizing that people will often call for help to stop impending violence by others in their social circles. Slutkin gives an example: “We got a call from a mom because her son and his friends were loading up weapons. She didn’t want to call the police on her son. She just wasn’t going to do that. … We were able to work with them for months, and no one went to jail. No one’s life was destroyed.” In Hanover Park, a former gang member named Gordon Debruin told me he’s called to ask for help with his own violent tendencies.

The question is whether any of those methods could work for intimate partner violence. And to that, Sharma shakes her head no.

Untraced Violence

Gun violence and intimate partner violence differ in many respects. Guns are often associated with gangs, whose violence is codified, profit-minded, impersonal and out in the streets. Intimate partner violence is none of those things; tension won’t clear out the park, and there is nothing to reliably track via sound sensors. Nor is there someone who will call with a warning, Sharma says. It’s “usually behind closed doors … . There’s no third person there on the scene or who can come to the scene, you know? It would be incredibly difficult, unless you were living in a commune or a big joint-family dwelling.”

But cultural shifts have begun to chip away at the traditional divisions between the public and private realm. Slutkin sees an opening for interrupters. “The idea that this is in the home, it’s a private matter and it’s no one’s business,” he says, “that idea is starting to crack.”

“They are actually being called upon to help a lot in these situations,” he says about CeaseFire workers in Chicago, who are untrained in intimate partner violence issues. “They already helped someone with their brother, so why shouldn’t they help with their sister?”

In Auburn Gresham on the South Side, Autry Phillips confirms that. When asked what those moments are like, Phillips sighs. “Stressful,” he says. “The person who is getting beat has to acknowledge that ‘I should not be getting beat.’”

Victims’ hesitation to acknowledge their abusers’ behavior as wrong is a problem identified by interviewees in both the U.S. and South Africa. For every woman like Mireille, who is ready to re-evaluate her relationship — or who might call interrupters, if such a service existed for her — there are others who are not. Abusers, Sharma says, “target who they can. It’s someone they can control, who they have groomed to be controlled.”

Derrick Jensen agrees. An author and activist, he has written about his father, who physically abused his mother and siblings and sexually abused his mother, sister, and him. “The worst thing my father did went beyond the hitting and the raping to the denial that any of it ever occurred,” he wrote in A Language Older Than Words. So deeply internalized is this compliance, Jensen says, that “a lot of times, people who are trying to help a victim escape end up throwing up their hands, because of learned helplessness,” a depressed passivity that comes from enduring inescapable suffering until avoiding it seems impossible.

Arguably, the problem of a victim’s lack of clarity suggests that more contact, not less, is better. While Slutkin proposes assessing abused people at “any and all medical and health visits,” a single 15-minute visit might do little to create lasting change. The CeaseFire model works when the individuals at risk are in frequent contact with interrupters. This tends to involve providing social services that meet high-risk clients’ self-perceived needs, finding reasons to connect before guns are in someone’s hand. Phillips mentions food banks as an example; Hanover Park shares its offices with healthcare providers that cater to low-income populations, such as HIV/AIDS services and drug counseling. These forms of assistance work because gang violence tends to be confined nearly entirely to communities with high rates of unemployment and poverty.

In contrast, no socioeconomic category captures all of the people abused by their partners. Although experiencing other forms of violence can exacerbate the problem, this phenomenon is found in every demographic — including among Ph.D. students like Mireille and David. How could violence interruption work for people who aren’t needy, and whose problems, while potentially deadly, aren’t as loud as a gunshot or as obvious as a hot block?

Stopping Violence With Conversation

Here, South African insight may be particularly powerful. In a country where 500,000 rapes are committed each year the American idea that removing a woman from a particular relationship ends violence appears less than useful; men simply go on to abuse their next partners. Rather than organizing services after the end of relationships, therefore, South Africans are willing to engage with people who have not yet left abusive partners — and, like CeaseFire does, engage with the perpetrators directly.

Joyce Doni of Rape Crisis Community Trust in Khayelitsha, a black township outside of Cape Town, is enthusiastic about this. “We’ve just decided they need to be put behind bars, but … there will come a time when he’s being released from jail,” she says. “So how can we then help see that the same monster that was behind bars can come to us as a better person?”

Doni says she’d work with violent men if her organization’s funders permitted it. Primrose Tetyana, a counselor at Mosaic, an organization offering support to survivors of domestic violence in Khayelitsha, actually does.

Tetyana tells the story of one woman she’s been counseling. Abused by her husband, she’d come to counseling fearing for her life. “They had been in a good relationship before,” Tetyana explains. “He was a good husband, respectful father. But after a while, according to her, he began to drink a lot of alcohol. After drinking, he’s going to be violent, very violent … . She’s experienced all kinds of abuse. All kinds. She didn’t want him arrested, [but rather] just to talk.” The woman also declined Tetyana’s advice to move into an emergency shelter with her children. “She is thinking of leaving him, but not now.”

But Tetyana’s client had done something Americans would find novel: She’d begun using the court system to pressure the man into changing. Like America, the South African system offers court orders to protect women. But rather than to using courts to simply terminate contact after a relationship ends, women here have the option of securing a protective order from a magistrate’s office that would result in increased police attention on her abuser — which Tetyana (and other interviewees) framed as a means to motivate better behavior.

Faced with a wife intent on change, not divorce, Tetyana did something CeaseFire might find intuitive: She focused her efforts on the perpetrator. After discussing the risks with her client, she wrote him a letter. She asked him to come to her office “to talk about his anger,” Tetyana says. She says she’s talked to “men who are using violence” many times, often mediating fraught discussions between spouses or helping end a relationship safely.

She gives public talks too, she says, and recruits abusers into counseling from these sessions. “Instead of killing or abusing someone, you work towards your feelings in order to change your aggressive behavior,” she says, to become “a respectable partner and father.”

Tetyana says she’s had some success. Twenty percent of men accomplish real change, while “maybe 40 percent decide to leave the relationship” in which they committed abuse.

Tetyana has never heard of Gary Slutkin, but a description of his model of interrupting violence clearly excites her. In her community on the Cape Flats, she has too learned to stop violence with conversation.

An Alternative

“I’m not saying it shouldn’t be tried,” Sharma concludes about domestic violence interruption.

The challenges she and others perceive are hard to refute. How to find, contact and remain engaged with people suffering intimate partner violence remain unanswered questions.

Yet there may be little to lose in trying. Efforts to improve legal penalties in America have found limited success. A 2008 analysis found five out of six domestic violence cases in and around Chicago ended in dismissal. In 2013, Chicago Metropolitan Battered Women’s Network concluded that “unprepared courtrooms … tell victims their requests are not important.” Nor do convictions offer hope: An evaluation of Illinois’ multidisciplinary program reported poor improvement in nearly all justice outcomes. Over 10 years, almost four in 10 abusers are booked on repeat domestic offenses. While Mireille secured a protective order, she seems to have little confidence about the courts.

Cape Town is similar. Domestic violence is rampant, and although four in 10 South African men say they’ve raped, only a small minority of incidents are reported and rape case conviction rates are very low.

To be clear, no one at Ceasefire is suggesting handling rape cases. Despite their success, the programs in Chicago recently underwent a temporary shutdown due to state budget cuts; in the near term, they’ll be restarting the current work and don’t have plans to expand. The five violence interrupters in South Africa — some of whom are exceptionally self-sacrificing — are at capacity with their current workload.

With all that said, South Africa might be the right place to give the idea a try. Daphne Croy, who handles sexual violence cases at the nearby Philippi Police Station and runs an NGO addressing violence against women, expresses strong interest in the method: “I’ll bring it up at the next workshop.” In Khayelitsha, Joyce Doni is enthusiastic too.

Even if the efforts backfire, abuse survivor Derrick Jensen says he “would have loved” someone to interrupt his father’s abuse. In A Language Older Than Words, he describes a surprising side effect of even unsuccessful attempts to help victims: “Had I never known an alternative existed — had I believed that the cruelty I had witnessed and suffered was natural or inevitable — I would have died.” By simply showing up, interrupters might offer hope that the insanity of violence isn’t the only option that victims of domestic violence have.