Silvia Fernandez loved each of her three children, but Oscar was her special one.

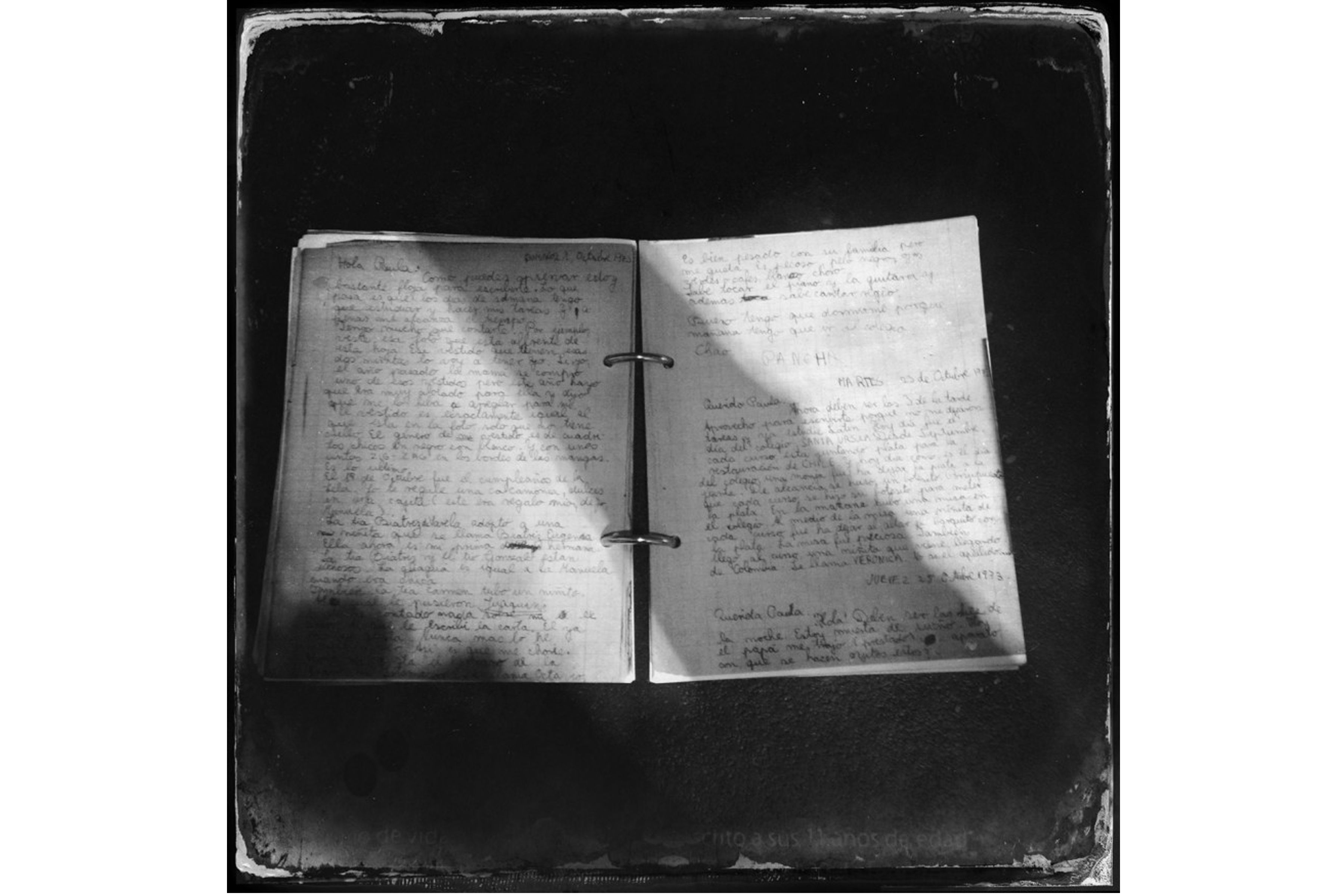

A caring brother and cousin who always arrived home on time, he was the top student in his class five straight years in elementary school. Oscar earned his rank even though he’d listen to loud music while studying in his room on the top floor of the family’s two-story home.

The mother’s bone-deep love for her boy made his death on April 9, 1985 a devastating blow.

The police of the Pinochet dictatorship shot Oscar in the back. Two operations could not save him.

After years of grieving, Fernandez has come to feel joy again through her other children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren, and to find purpose in her ongoing fight for truth and justice.

But the pain from Oscar’s murder has never fully receded.

“We have five fingers,” she said. “If you cut one off, if something happens, it’s missing for the rest of (your) life. It’s not going to grow.

“That happened to me,” Fernandez said.

Her anguish is a shared one.

Chile had coups before 1973 as well as a long tradition of government of relating to its citizens the way a ruler treats his subjects. But the period that was bloodiest and the history that resonates loudest began with the September 11 coup headed by Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Over the next 17 years the government instilled and maintained a climate of complete control and fear. Thousands of Chileans were murdered, tortured or disappeared.

Forty years after the Pinochet takeover, memories of those dark years lie uneasily within many Chileans.

For thousands, it’s because they have murdered relatives whose whereabouts remain unknown, making closure elusive.

But for others like Hernan Gutierrez, owner of a chocolate shop in the seaside town of Algarrobo, the lingering distress stems from what he witnessed.

Just 13 years old when the Pinochet coup happened, he still remembers walking to school along the Mapocho River and seeing bodies float by day after day.

“It was for a long time,” said Gutierrez, who moved his family to Germany for much of the 80s so that his two sons would not grow up under a dictatorship. “Santiago, as the capital, was the most affected by the death and disappearances.”

His father didn’t allow him to get close enough to see everything, but Gutierrez could tell that many of the bodies had been shot with high-caliber bullets.

Some had been decapitated.

Gutierrez’s memory of seeing the floating corpses makes him question how others can deny knowing about the regime’s activities.

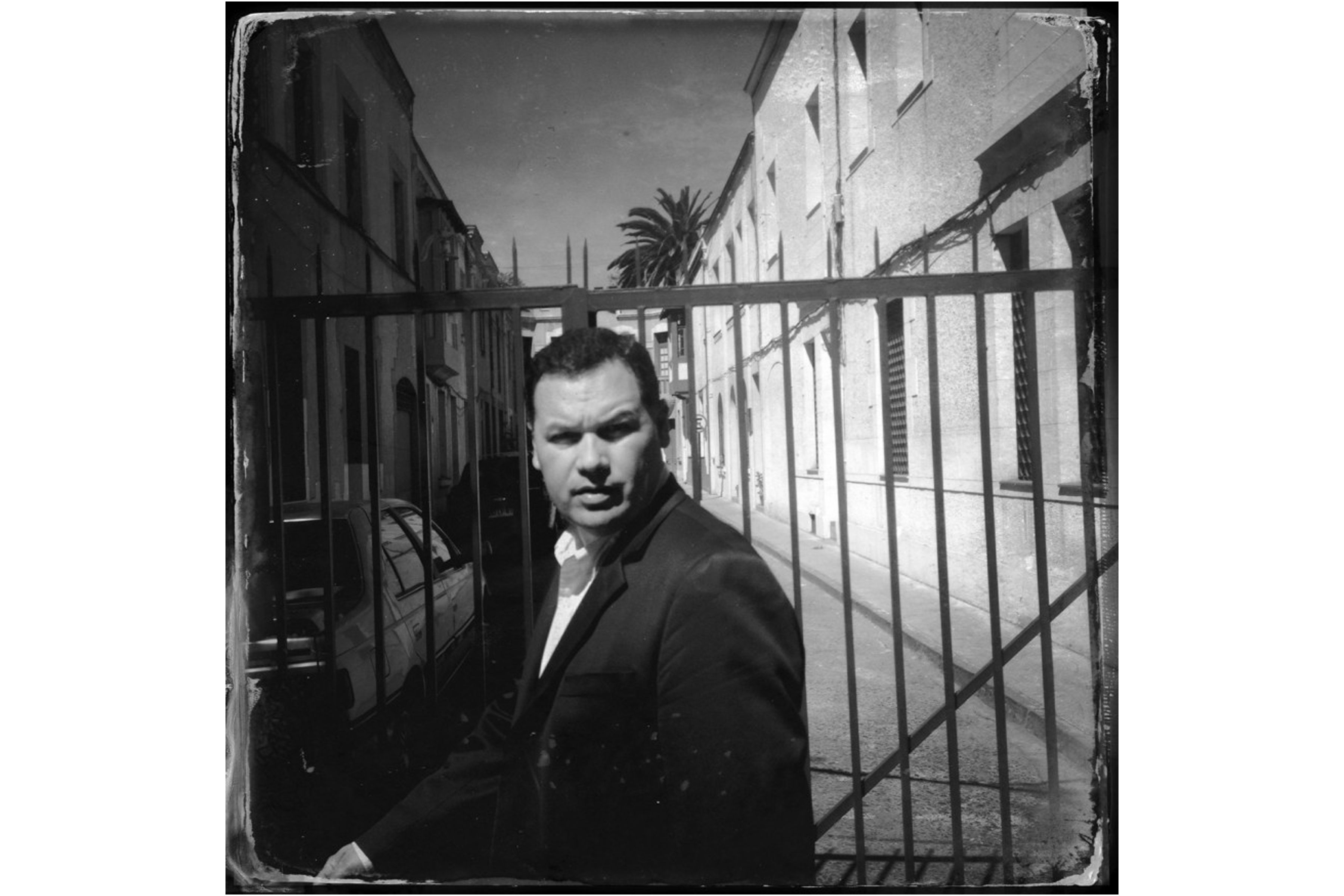

Mario Hernandez knew.

A diminutive, sturdy 60-year-old with an energetic manner and boyish face, Hernandez has worked at seafood restaurant Los Patitos in Algarrobo for more than four decades.

Pincohet’s reach extended far beyond Santiago, he said.

In Algarrobo, which lies about 100 km west of Santiago, people were disappeared and did not return.

Hernandez brightens when he talks about having waited on former President Salvador Allende, legendary poet Pablo Neruda and Neruda’s third wife Matilde Urrutia. But he shudders with disgust when he recalls serving high-ranking generals from Pinochet’s inner circle.

“For me it was something very painful, but for my work I had to do it,” he said.

The nation has taken on the work of confronting its past more publicly in recent years.

In 1994, Villa Grimaldi, a former restaurant turned torture and detention center, was converted into a peace park. Nearly all of the buildings on the property were reconstructed from survivors’ memories, as Pinochet’s secret police destroyed all that they could when the facility was closed in 1978. Visitors can see some of the rusted railroad spikes that were used to weigh down victims’ bodies as they were tossed into the ocean from a helicopter.

In November park officials collected artifacts from torture survivors like Carlos Contreras. He brought a paper chessboard he had made and kept for nearly four decades. Contreras cut the green and white pieces out of construction paper, and played with other detainees while they were imprisoned at Tejas Verdes, a detention center just south of coastal town San Antonio.

In 2006 the government declared Patio 29, a notorious site in Santiago’s General Cemetery where the bodies of hundreds of the regime’s victims were dumped anonymously, a national monument.

Then-President Michelle Bachelet, like her mother a torture survivor, presided over the official opening in January 2010 of the Museum of Memory and Human Rights. Over three floors visitors can listen to the final speech Allende delivered from La Moneda as bombs dropped on the presidential palace, read secret decrees authored by Pinochet in the days and weeks after the coup, and watch a video of a woman fighting with green-suited carabineros to place a single flower in a park in honor of her murdered husband.

A gallery of small, framed black-and-white photographs of the disappeared hangs along a wall that spans the second and third floors. Some of the frames are empty.

Beyond these officially-sanctioned public spaces, the fortieth anniversary of the coup this September saw an eruption of memory-related activity.

The national television station showed hours of previously banned images. Plays, book releases, scholarly conferences and memorial events took place from Arica in the north to Punta Arenas in the south.

It was a marked change from 20 years ago, according to Hugh Rojas, a sociology professor at the University of Alberto Hurtado. At that point, Pinochet still headed the military and served as an unelected senator for life.

But silence has largely returned after the deluge. Those who continue to talk about these issues can pay a social price, Rojas said,

According to a national poll published shortly before the anniversary by professors at the Catholic University, nearly half of Chileans say they feel that it’s time to turn the page on that chapter in Chilean history and move forward.

Ana Gonzalez disagrees.

The feisty 87-year-old with bright red fingernails and an unslaked thirst for truth survived many detentions and the disappearances of her husband, two of her sons, and a pregnant daughter-in-law. Gonzalez pays tribute to her murdered relatives by continuing to wage a joyful struggle for justice and against oblivion: “When you take this path of liberation..., you know that you can die at any moment. But those of us who remain are not going to allow that to happen because forgetting is death. Because of that, memory is essential.”