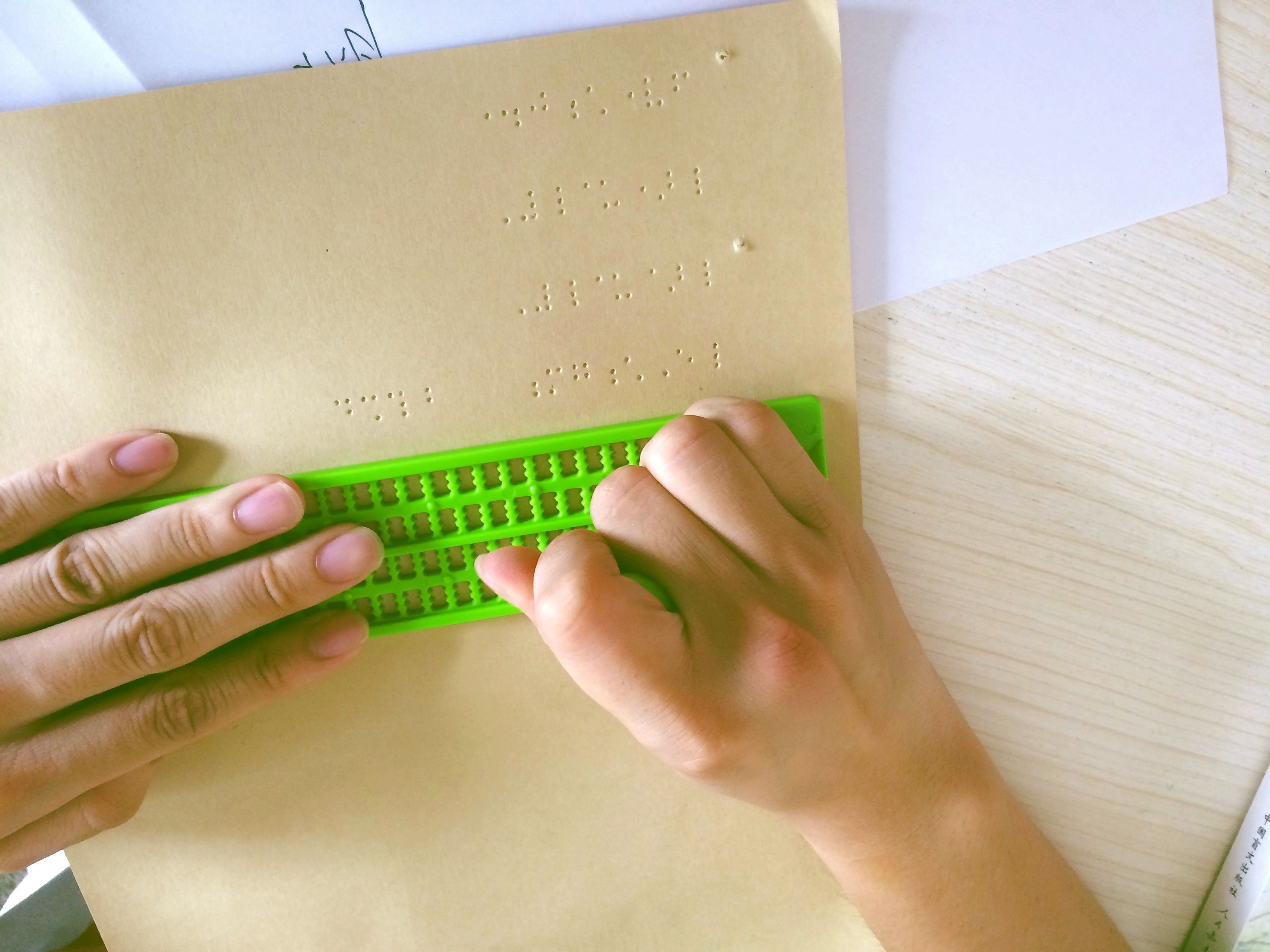

Ming, 13, sits at the front of the classroom as he writes in Chinese Braille. A newcomer to the Guangzhou School for the Blind, he lost his eyesight after a surgery for a brain tumor. He shows me how to use a stylus and slate to write Braille, his fingers moving rapidly across the paper. He says he learned Braille in two weeks after his surgery, but he also uses a magnifier to read sometimes. When asked to compare the school to his old high school, he says nothing.

While the Chinese government has increased spending on special education, devoting $87 million in 2008 to 190 new schools, many current schools still lack a clear plan for moving forward.

Rising amidst a crowd of tightly packed gray apartment buildings, cars crammed beside one another, and tangled electrical wires, the Guangzhou School for the Blind’s white and pink façade seems almost out of place. A lengthy school slogan stretches across the balconies of the second and third floors of the six-story open building, reading: “Respect your teachers, follow the rules, be diligent in your studies / Be self-sustaining, be independent, optimistic, and strive to improve yourself.”

Situated next to a partnering massage clinic, the school serves 323 students in elementary, middle, and vocational high school. A total of 118 teachers instruct 24 classes of students, and the three main classes are math and science, arts and culture, and life skills. Luo Guan Huai, the principal of the school, has an optimistic vision for its future. “Many Chinese haven’t accepted the blind…parents don’t want others to know they have children with disabilities,” he says. “But now the government’s emphasis on special education is great. Now our school has rapid development… Our hope is that students, after going to school here, can work in society like normal people.”

First founded in 1889 in the Guangzhou Boji Hospital, the school was the third blind school to be opened in China. Back then, and even now, many blind beggars would congregate at the nearby San Yuan Gong Temple. In particular, there were many blind girls. “There was a zhong nan qin nu problem then,” Luo says, referring to a popular Chinese idiom meaning “to regard men as more important than women.” According to Luo, an American missionary doctor took in the blind girls and eventually created a school for them. While that school ceased operation in 1971, it reopened in its current location in September 1989, expanding into a 4,800 square meter campus.

Luo praises recent governmental initiatives for special education as beacons of reform, yet the massage clinic stands as a testament to a lack of change. All high school vocational classes are based on training students to be masseurs, the only vocation that many in China assume blind people can accomplish. “Blind people have blind specialties,” Luo says. Yet when asked about the massage clinic, he counters, “but having all students learning this is unacceptable.”

He mentions that a few students from the school have gone on to pursue other careers. College psychologists, hospital workers, graduates who have opened their own massage clinic, and three graduates who returned to teach here—as the only blind teachers in the school—are among the few success stories. “We can’t satisfy all students anymore,” Luo says. “We must be as good and as competitive as regular schools.” It seems a far stretch, but Luo claims that “the government is really emphasizing that.”

In a cluttered classroom with a green chalkboard and a large sign reading “study well,” a group of young middle school students sit on top of the wooden desks, chatting with each other. It’s one of the last days of school for the semester. Others are sitting down, using the computers scattered across the desks. Applications on the computers can read words out loud to the students and help them type characters. When I ask them about their aspirations, one female student shouts out that she wants to be an English-Chinese translator. “I’m reading Jane Eyre right now, in Chinese,” she says. Another male student wants to be a photographer and shows us his new iPhone, which he uses to take photos.

Ming sits away from the rest of the students and talks about his dreams of going to college and studying electrical engineering. “The doctors said I could get up to 70 percent of my eyesight back,” he tells me. “There’s hope.”

*Ming’s name has been changed to protect his identity.