Yulia Marushevska has never been a customs officer before. Nor has she been a politician. But today, at 26, she is a member of Odessa’s regional government with perhaps its most difficult job: cleaning a notoriously corrupt customs house.

“There are a lot of people with a huge experience who worked in this country after the collapse of Soviet Union,” she says when challenged about her lack of experience. “But what they did achieve? What are the results? The most corrupt customs in the Eastern Europe.”

For decades Odessa has been akin to Chicago under Al Capone, full of mafia and local officials in bed with them. And for decades the Odessa port was the center of this city’s corruption, facilitating what officials say is as much as $40 million a month of graft that greased the wheels of power. She says her predecessors paid as much as $5 million to have her job, since they knew they could steal even more than that.

“The intelligence forces, the police, the prosecutors…all other enforcement agencies…it was obvious that these people were just using the possibility to ask for money,” Marushevska says.

Ukraine’s old system was so broken, the government that came to power in 2014 has turned to foreigners and complete novices. Marushevska embodied Ukraine’s pro-European ambitions: youthful, elegant, untainted by prior politics, and carrying the right pedigree.

In 2014, her “I am the Ukrainian” YouTube video went viral and made her the face of the Maidan revolution, which toppled a pro-Russian and deeply corrupt government.

“We want to be free from the politicians who work only for themselves,” she said to camera. Her anti-corruption call to arms was viewed 9 million times.

She’s quickly discovered winning was easy and governing is harder.

“On Maidan, I thought that everything can be done only with your will and wish to change,” she said. “And now I understood that it is a huge work, a huge job to do.”

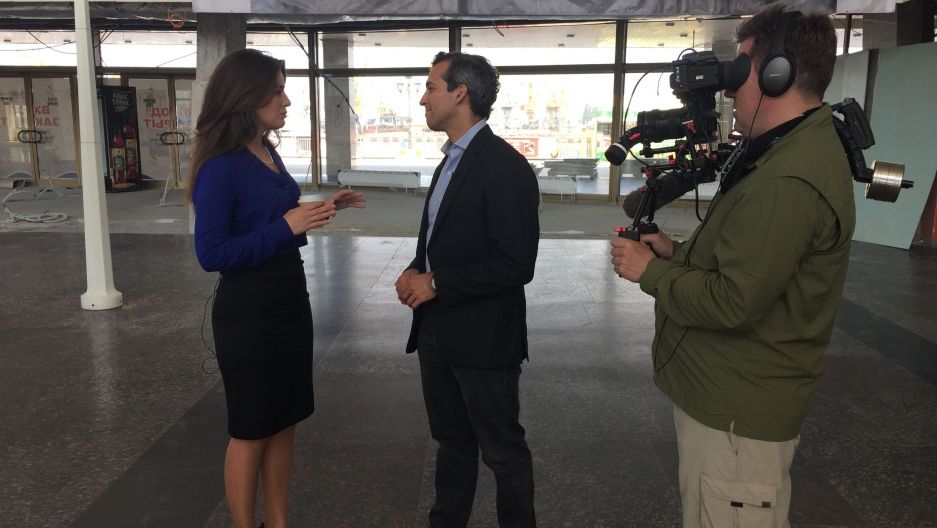

Her huge job starts in a cavernous building in Odessa’s port. The well-lit and relatively modern “Open Customs Area” will replace an old, dark building with offices in the basement. The building’s architecture is its message: customs officials who used to work in back offices will now have desks out in the open; workers susceptible to corruption will be replaced by computers; procedures will be simplified to prevent graft. The United States is helping fund the project.

“It’s customs as a service, not as a barrier, for business,” she says. “It is a symbolic place and a symbolic project for whole Ukraine.”

But when you fight corruption, corruption fights back. She accuses the chief Ukrainian customs officer—a member of the central government and someone who is technically her boss—of trying to block her reforms by installing a spy as her deputy.

That deputy was sent to “spy and to control,” she says. “That's this old practice of a criminal's world when they’re sending in their people to watch what's happening.”

She was able to block the deputy’s appointment. But so long as the old elites are still in power, it’s not clear whether she can succeed. Her main ally is the local governor—who’s even more of an outsider than she is.

“This country had had unchanged elite for 25 years,” says Odessa Governor Mikheil Saakashvili. “These guys, they miserably failed the country.”

One year ago Saakashvili was appointed to be governor of Odessa—and granted Ukrainian citizenship—in order to fight corruption. His last position was as president of the former Soviet state of Georgia, fighting Russian President Vladimir Putin.

He’s still a thorn in Russia’s side, but his most pointed criticism is now for fellow Ukrainians.

“I don’t think Putin can defeat Ukraine,” Saakashvili says. “I think Ukraine can snatch defeat out of the the jaws of victory. It can only defeat itself."

He accuses the politicians who have been running the country of widespread corruption. Last December in a Cabinet meeting, he called out the Ukrainian interior minister, Arsen Avakov. Eventually Avakov had enough; he threw a glass of water on Saakashvili.

Saakashvili stood up and repeated his accusation. He seems to be unwilling or unable to pull punches. “We have tens of thousands of Russian soldiers attacking Ukraine. That's a fact of life. But also we have 1 million or so strong army of Ukrainian bureaucrats that basically are trying to demolish this country.”

For Saakashvili, Ukraine’s fight against corruption is just as life and death as the fight on the front lines against separatists.

Asked what happens if his anti-corruption campaign fails, he says, “Ukraine has no option to fail because it will lead to disintegration of the country.”

That disintegration is exactly what Marushevska is trying to prevent.

“It's war of past and future,” she says in the Open Customs Area. “A war against corruption, war against this old way of thinking, war against Soviet heritage, and war for a modern Ukraine.”