MYSLOWICE, Poland — The children Karolina Zolna knows huff and puff after a few minutes of exercise. Two years ago, her infant daughter spent four months in the hospital with pneumonia. The doctors did not identify a cause, but to Ms. Zolna, the reason for the baby’s illness was obvious.

She blames the pollution that hangs heavy in the air of her gray hometown in Poland’s coal heartland, Silesia. In the still-chilly early days of spring, thick smoke wafted from most of the chimneys in Myslowice, wreathing the town in a haze that is a constant reminder of residents’ reliance on coal for heat.

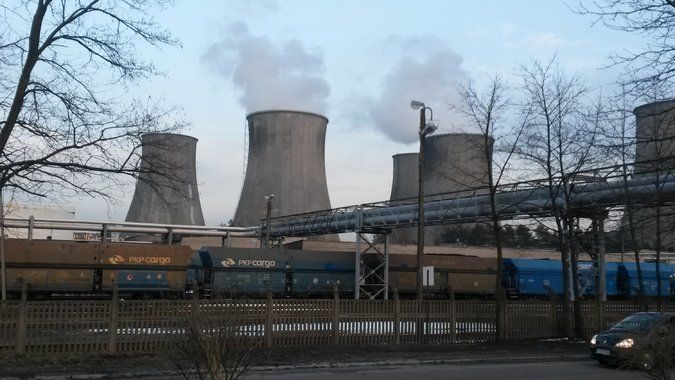

A few kilometers away, visible from the town’s main street, stands the tall red and white smokestack of Elektrownia Jaworzno III, a coal-fired power plant. Clouds of white steam billow from its concrete cooling towers.

“It’s definitely too close to people’s houses,” Ms. Zolna, 30, a school secretary, said of the plant. “If you read about this, you know that pollution is not good for health. And if you have children, you know that it affects your children. And there are more and more kids” with breathing troubles, she said. “Both my children have had problems with their lungs.”

Poland has the highest levels in Europe of the tiny pollution particles that are strongly linked to serious health problems like heart attacks, strokes, cancer and even dementia, said Martin Adams, an air quality expert at the European Environment Agency. Poland is home to six of Europe’s 10 most polluted cities, the agency’s figures show.

That filthy air is largely a result of Poland’s heavy reliance on both hard coal and lignite, which is also known as brown coal.

With energy policy on the agenda as the Group of Seven leaders meet this week, clean power is still in its infancy in Poland, where a tangle of political and economic forces have kept coal secure in its place as the dominant fuel. About 85 percent of electricity and 43 percent of heat come from the fuel some call “Polish gold,” the government estimates.

The European Commission has opened infringement proceedings against Poland for violating particle pollution levels and is investigating reports that it has also exceeded limits on nitrogen oxides.

The health consequences are severe. In addition to its role as a major source of climate-warming carbon dioxide emissions, coal burning releases a bevy of dangerous pollutants, including, in the low-tech home heating systems that are common in Poland, toxins like benzo(a)pyrene.

More than 43,000 Poles died prematurely because of air pollution in 2011, the most recent year for which figures are available, the European Environment Agency estimated.

“It’s a myth in Poland that coal is cheap, and energy from coal is cheap,” said Julia Michalak, an energy expert at demosEuropa, a Warsaw research group. “We pay for it a very high price.”

Poland’s government is among the European Union’s staunchest defenders of coal, leading opposition to measures that would restrict its use.

Despite troubles that have roiled the country’s mining sector this year, officials see coal as key to avoiding dependence on Russian natural gas. Coal’s backers also say it is an affordable option for a nation that cannot afford a quick transition to cleaner alternatives.

Awareness of the severity of the air problem has just begun to dawn. Prime Minister Ewa Kopacz’s government declared 2015 to be the Year of Improving Air Quality and is backing a proposal to empower regional authorities to clamp down on pollution from vehicles and from the burning of coal and wood in homes.

Officials are focused on the contributions of home heating, known as low-stack emissions, which are severe and very visible. Millions of Poles burn coal, often the cheapest, most polluting grades, in old furnaces with poor filters. Some add plastic or other garbage to the mix, making for an even more toxic brew. Thick black smoke billows out of chimneys for nearly half the year, stinging throats and eyes and shrouding whole neighborhoods.

Environmentalists say the government’s plans for addressing that pollution are feeble. Many also argue that any serious attempt to clean Poland’s air must also confront coal-fired electricity generation, an area officials do not see as a problem.

Pollution from coal-fired power plants in Poland causes about 5,300 deaths per year, Greenpeace said in a report commissioned from Stuttgart University. The sector creates health costs ranging from 3 billion euros to 8.2 billion euros, or $3.3 billion to $9 billion, each year, said the Brussels-based Health and Environment Alliance, or HEAL.

Krzysztof Bolesta, an adviser to Environment Minister Maciej Grabowski, said that the power sector, while not pollution-free, is not a significant contributor to Poland’s air quality problem. Emissions from coal-fired plants are covered by tough European regulations, he said. “You can’t really find a robust study on health issues attributed to just one particular source of combustion,” he said. Coal-fired plants “will never be zero emission, of course,” he said. But “they meet the legislation, so it’s off the radar, because they are sufficiently tackled, if you will.”

Enrico Brivio, a spokesman for the European Commission, said the body did not have details on individual plants’ compliance with its rules, since enforcement is the responsibility of national governments. Polish power plants have been granted extensions for meeting European requirements, so their pollution caps are higher than those imposed elsewhere.

Monika Morawiecka, a member of the management board of the Polish Electricity Association, an industry body, said coal-fired plants had cut emissions drastically since 1989. The utility PGE, which generates about 40 percent of Polish power, has reduced particle pollution by 98 percent, sulfur dioxide by 89 percent and nitrogen oxides by 46 percent in that time, with further declines expected, she said.

“Compared to what it was 25 years ago under Communism, the improvement is tremendous,” said Maciej Bukowski, the president of the Warsaw Institute for Economic Studies. “We are living in a different world.”

But Meri Pukarinen, the head of the climate and energy unit at Greenpeace Poland, said the government focus on home heating and transportation was indicative of an approach that is “quite skewed, not appreciating the health impact of the high-stack and energy production industry at all.”

“It’s a first step to focus on low-stack emissions, because it’s the most evident for people and they can feel it, they can see the smoke coming out of the chimneys,” said Weronika Piestrzynska, a spokeswoman in HEAL’s Warsaw office. “It’s harder to confront” the power industry, she said.

In Myslowice, as a pungent cloud of smoke drifts from the chimney of a nearby apartment building, it is clear to Ms. Zolna, the school secretary, that both sources contribute to the foul air choking the town. “It’s not only because we use coal stoves,” she said. “We do not use them year round. It has to be these power plants.”

Coal’s share of Poland’s power base is slowly declining and is expected to continue doing so, as tougher European Union rules kick in. But new plants and upgrades and expansions to existing ones are still going forward.

Shifting from a coal-based economy to one built on cleaner fuels will take vision, said Ms. Michalak, the demosEuropa expert.

“What we need here is not incremental change, what we need here is a big decision about where we will go and how we will get there, and this is something that Polish politicians don’t have an appetite for,” she said. The country’s leaders, shaped by its move from Communism to democracy, she said, “are not ready for another big transformation.”