The first plague hit long before the second one struck this year.

“The COVID-19 pandemic is pulling the lid off conditions that we have not addressed for generations,” said Bill Bynum, CEO of Hope Credit Union, which serves low-income communities in Mississippi. “These rural and high-poverty areas are being hit harder, because they’re so much more fragile.”

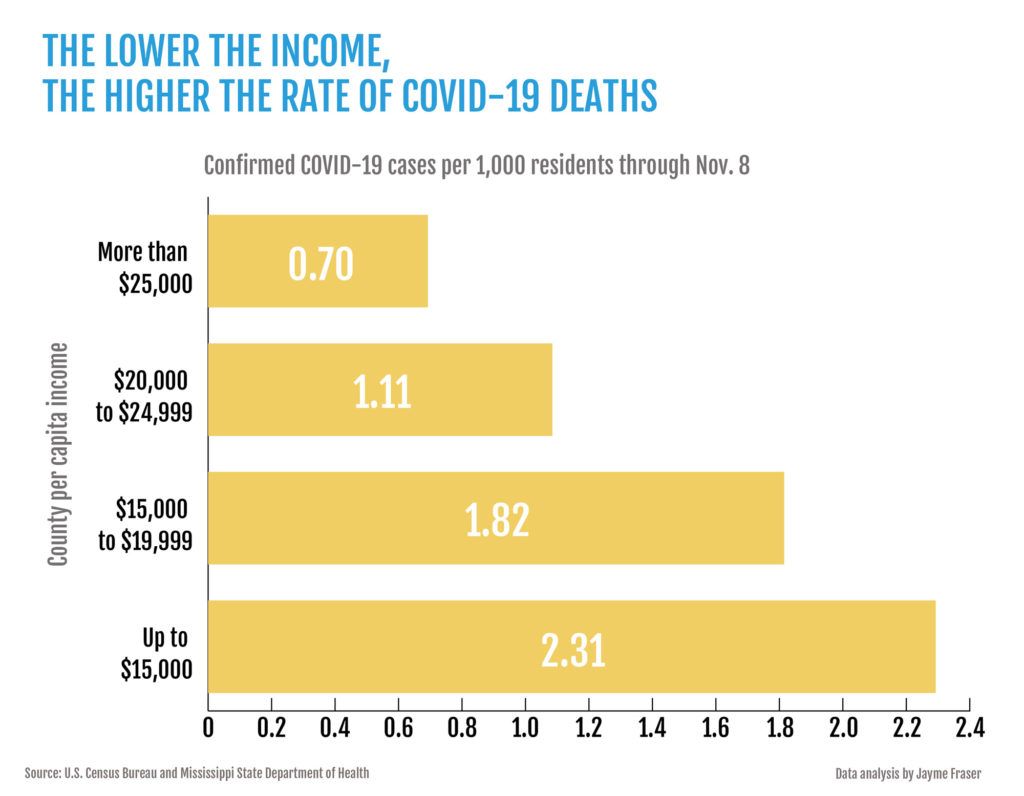

The Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting conducted data analysis showing that coronavirus deaths are twice as high per capita in Mississippi’s poorest counties. The death rate rose to 3.3 times higher when compared with counties where the per-capita income was at least $25,000.

Persistent Poverty Fuels Fragility

Bynum said that fragility stems from health woes, which poverty fuels, affecting a third of Mississippi children and nearly half of all Black children.

“These are communities where wealth has been extracted, where the poverty rate has been over 20% for half a century,” he said.

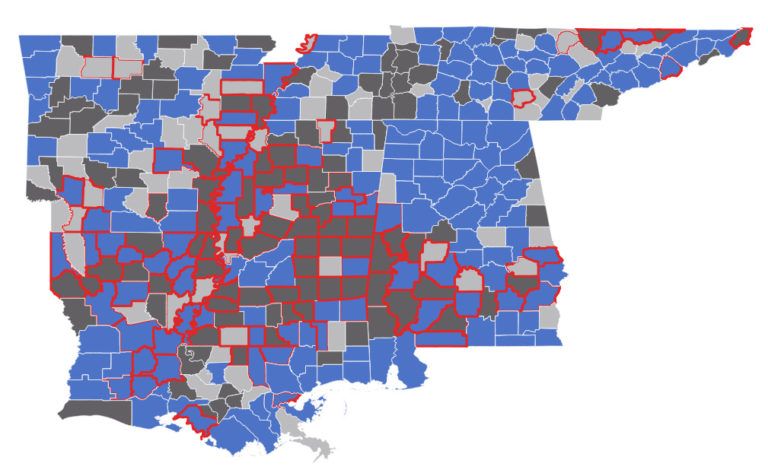

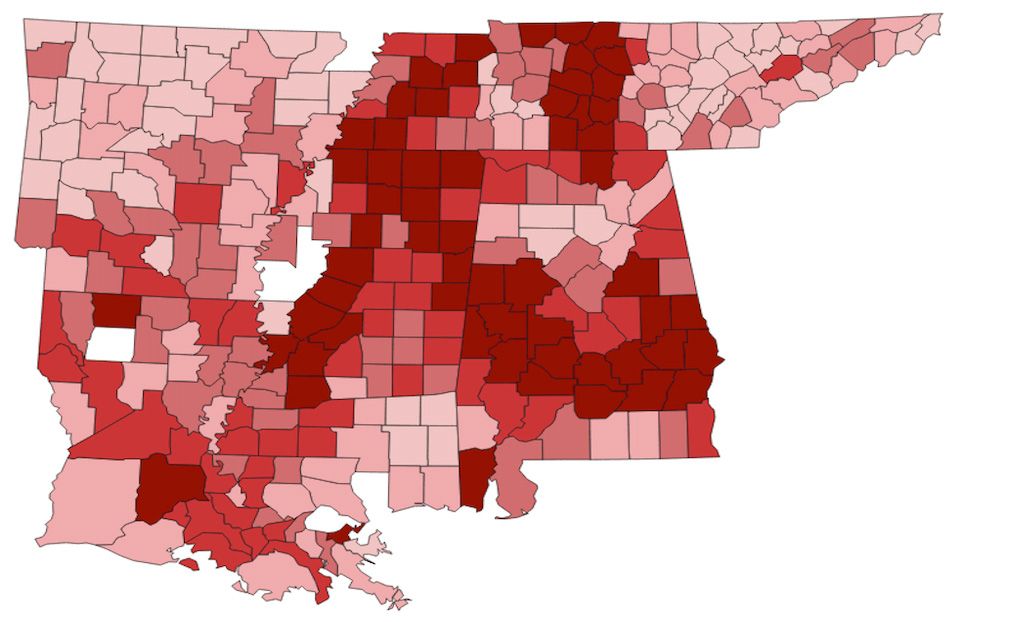

Such poverty goes back centuries, Bynum said. “You can take the map of where slaveholding was concentrated and overlap that with the worst health outcomes, the highest unemployment and the worst education outcomes—they’re the same places.”

In fact, he said, much of the nation’s persistent poverty can be found in three states—Mississippi, Alabama and Louisiana.

Overall, nearly two-thirds of Mississippi’s counties suffer from persistent poverty, the U.S. Department of Agriculture reports.

Bynum said inadequate housing, lack of transportation, financial woes, discrimination and violence have plagued these impoverished places for generations, fueling increased stresses on health.

Many in these impoverished counties work in low-wage jobs that don’t include health care as part of their compensation, Bynum said. About 40% of Mississippians who lack a high school diploma possess any kind of health insurance.

As a result, he said, Mississippi has “some of the most medically underserved in the nation.”

Since the pandemic began, poverty has deepened.

Mississippi vs. Medicaid Expansion

Dr. Leandro Mena, director of the Myrlie Evers-Williams Institute for the Elimination of Health Disparities at the University of Mississippi Medical Center, said the state’s poor—many of whom are already battling diabetes, hypertension and related diseases—suffer from a lack of access to quality health care.

Rural hospitals often have fewer intensive-care beds, “especially in areas where you have high proportion of uninsured residents,” he said.

Mississippi Department of Health data show that 60% of the state’s counties have no intensive-care beds, forcing many Mississippians battling for their lives to travel more than an hour to receive care.

Mena said that COVID-19 has exposed our “imperfect, poorly designed health care system.”

Leroy Johnson, a supervisor in the state’s most impoverished area, Holmes County, said the lack of health-care funding to rural areas made COVID worse in Mississippi, including the shutdown of five rural hospitals since 2014.

Those may not be the last. Nearly two-thirds of these rural hospitals are “vulnerable” or “most vulnerable” to closure, according to a study earlier this year.

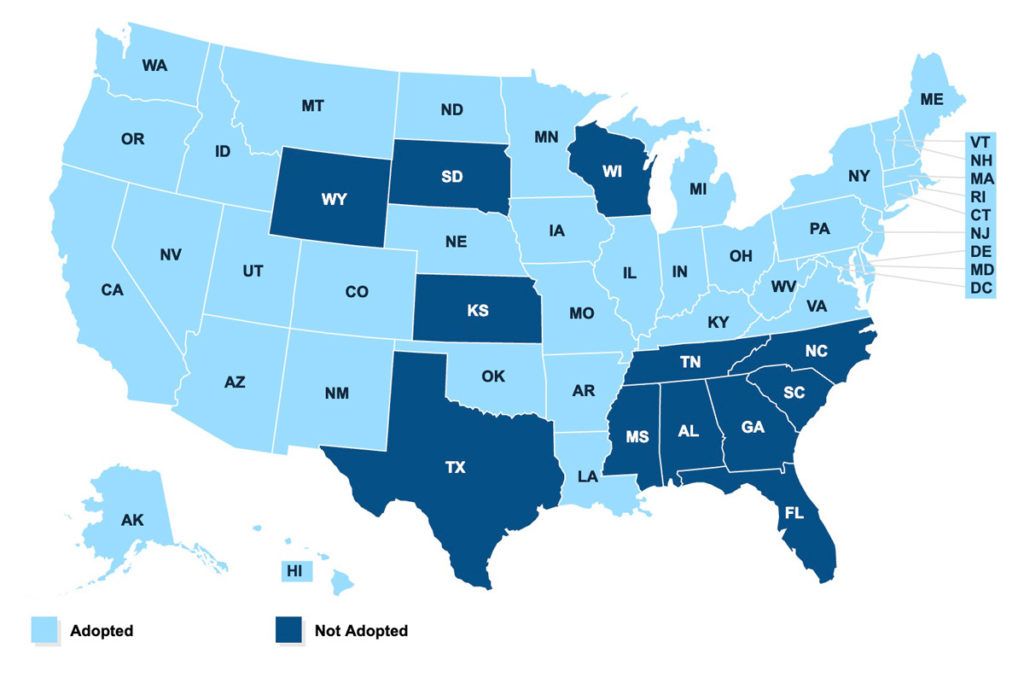

Johnson pointed to Mississippi’s refusal to expand Medicaid—as Tennessee, Arkansas and most other states have done—which would have meant about $1 billion more a year in health-care funding for Mississippi. Overall, the state is leaving more than $11 billion on the table that it could receive toward health care over the next decade by failing to expand Medicaid, healthinsurance.org reports.

That would be a life preserver to many of the state’s rural hospitals, nearly two-thirds of which are losing money and vulnerable to closure.

Gov. Tate Reeves said he wants better access to health care in rural Mississippi, but he did not explain how. He continues to oppose Medicaid expansion, saying the pandemic should be no excuse for adopting “very liberal policies, and I don’t think that’s a very smart thing to do right now.”

Voters in Oklahoma and Missouri thought otherwise, approving Medicaid expansion months ago. That raises the total number of states approving expansion to 38 states.

In a 2016 study, the National Center for Health Statistics showed that more than twice as many people living in states that have not expanded Medicaid failed to get care they needed because of the costs.

Fresh vegetables and fruits that can help improve health are now hard to find in some rural and impoverished places in Mississippi, a Feeding America study shows. As a result many living in the state’s poorest places must travel miles to buy this healthy food.

“Not everybody can get a Nissan plant to locate in their community,” Sandra Shelson, executive director for The Partnership for a Healthy Mississippi, said. But to towns like Utica, she added, a grocery store could mean just as much as an auto plant.

Nearly one in five Mississippians live in a food desert—more than any other state.

Dr. Rick deShazo, a professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and editor of “The Racial Divide in American Medicine: Black Physicians and the Struggle for Justice in Health Care,” said this lack of fresh food contributes to obesity.

West Virginia leads the nation in obesity, followed closely by Mississippi, where 71% of adults are overweight and more than 37% are obese.

“This epidemic uncovers for everyone the underbelly of poverty and inequality we have,” said deShazo, who is also professor emeritus at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. “There’s no excuse for it with the wealth we have in this country.”

Johnson pointed to suffering in his Holmes County.

The state’s policies “have been hurting poor people,” he said. "Now those bad policies are killing people and crushing rural communities.”

Samuel Boudreau contributed to this report.

The Poverty & the Pandemic is a continuing series from the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting and the Pulitzer Center that captures the stories of people and places hit hardest by the nation’s worst pandemic in a century. If you would like to continue receiving these stories, please sign up for our newsletter.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.