Most Americans who visit Cuba recall having a time machine moment: their grandfather’s Chevy, showgirls at the Tropicana, or the absent reach of email. My version of time travel included a Lada and a red scarf — two symbols of my childhood in Bulgaria, a Communist nation that turned to democracy after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989.

Last year’s anniversary of this event — which had allowed my family to immigrate to the Western world 25 years ago — prompted me to examine how democracy and Communism each had affected my country. This awakened a stronger urge — to explore places of kindred circumstances, with Cuba as a natural choice.

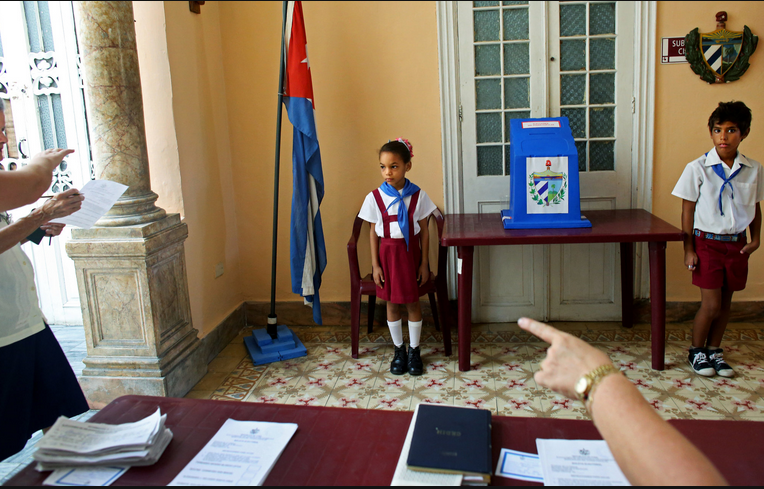

The recent warming of Cuban and American relations has been of particular fascination to me, as it has led to speculation over the future of Communism on the island. During my visit, I observed life in Cuba as only a native of the Soviet Bloc could — struck by the decorum of Communism, the appearance of choice that belied government involvement in nearly every aspect of daily routine. Cubans can vote, although limited to one-party delegates in a unicameral parliament.

Some private entrepreneurship is allowed, but restricted by a lack of advertising and steep taxes on business expansion. Artists toe the line of self-expression, knowing that if they cross it with a non-sanitized view of the country, they risk losing support from state-run galleries. Rallies, voting, and party activity from youth to old age are not mandatory, but reason for social and professional ostracism if they are omitted. Committees for the Defense of the Revolution that are peppered in every neighborhood promote community projects, yet also alert the government of dissident activities. Government control means safety, but often with a heavy hand that also restricts expression, travel and economic independence.

My project was not about political alignment: In both theory and practice, there are highs and lows to capitalism, as there are to Communism. It was simply a childhood relived, and my future imagined had democracy been just a whispered-about but never-seen guest. I saw myself in the child in a red scarf saluting voters, my mind too young for politics, simply eager to belong. Memories of my grandfather, who gave five youthful years to a forced labor camp after failing to show proper enthusiasm for the party, flickered through my mind as I saw photos carried by the Ladies in White, who still protest political imprisonment, despite beatings and detentions. One too many a family shared the familiar pain of separation via necessity — not an innate desire — for emigration.

All these parallels, while not sought out, are what a life straddling Communism and democracy had fine-tuned me to openly receive and record. Those who are bound by Cuba’s borders, those who observe life within as part of their profession or routine, do not often have this luxury.

I’d originally thought being from a former Communist nation would help forge a bond with Cubans. But I quickly learned that many weren’t sure of Bulgaria’s recent history — whether it was still Communist, nor the democratic changes introduced in the 1990s. Information that enters and exits the island is still very much government controlled.

Like the rest of the world, I am captivated by Cuba’s future — both as a Bulgarian and an American. Will the country’s borders open, releasing curious souls but thinning its population, as in Eastern Europe? Is the promise of a United States trade partner 100 miles away enough to end to a half-century-old trade embargo? Would an attitude of incentive, not one of disincentive, spotlight both what’s changing — and what isn’t?