August 29, 2015 | The New Yorker

By

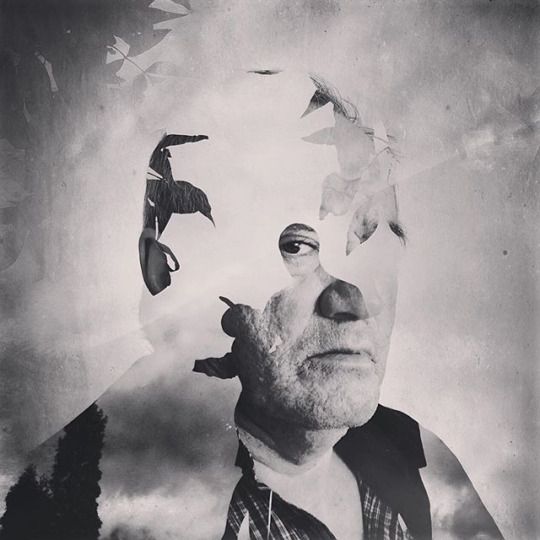

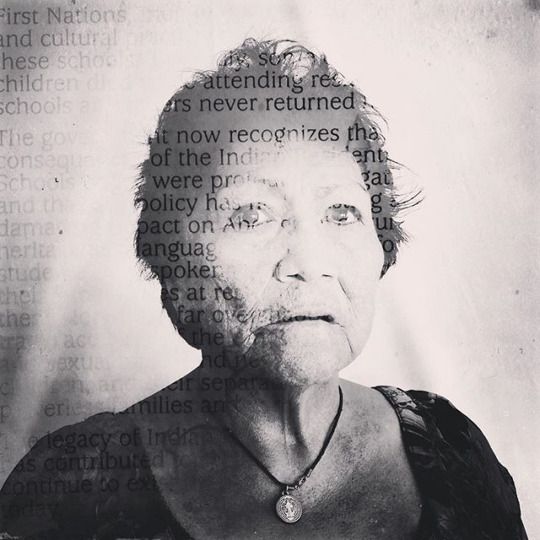

Daniella Zalcman

This is Daniella Zalcman @dzalcman and I’m back to share some images from my latest @pulitzercenter trip to Saskatchewan, Canada where I was reporting on the legacy of the Indian Residential School system just last week.

These forced assimilation boarding schools for indigenous children were federally funded and ran from the 1830s until 1996.

I will be sharing multiple exposure portraits of survivors from my project, as well as their stories, snippets of our conversations, and some historical context about Canada's painful relationship with its First Nations population.

For more images, head on over to @newyorkerphoto where I’m also taking over their account for the week! Thank you for following along!