The United Arab Emirates has been a reliable U.S. ally. It not only hosts several U.S. military bases on its territory but it also is a major purchaser of US arms, estimated by Fortune Magazine to have spent $28 billion since 2007. Luckily for its rulers and the U.S., the U.A.E. has not been a potential next-in-line for revolutionary turmoil. There are several storylines in the Middle East rumblings that can explain the U.A.E.'s steady state of affairs.

Egypt is a population giant and major political actor in the Middle East. Given its symbolic significance, its sudden transformation was cause for alert. Regardless of who is in power—Hosni Mubarak, a military junta or eventually a parliament-appointed leader—the U.A.E. will maintain good relations with Egypt. Its main concern is a peaceful transition in Egypt and the other states going through turmoil. Stability is paramount, and the U.A.E. has been careful not to issue hasty public statements. A 'wait and see attitude' is preferred; the U.A.E. believes that a prompt signaling of its intentions could be risky.

There have been unconfirmed reports that U.A.E. Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed Al Nahyan has invited Mubarak and his family to stay in the Emirates. Such an offer could well have been made, according to Abdulkhaleq Abdulla, a political scientist at University in Al Ain. Just as the late Sheikh Zayed, the U.A.E.'s former ruler, had offered to host Saddam Hussein and his family so as to avoid a U.S. invasion of Iraq, Sheikh Abdullah may have privately issued a similar invitation to Mubarak.

The U.A.E. has been deeply concerned with the uncertainty that a post-Mubarak era inevitably entails, especially given the possibility that the uprising could still be exploited by radical Islamists. With Mubarak's departure, the U.A.E. may also be seeing itself in a weaker position vis-à-vis Iran's regional ambitions.

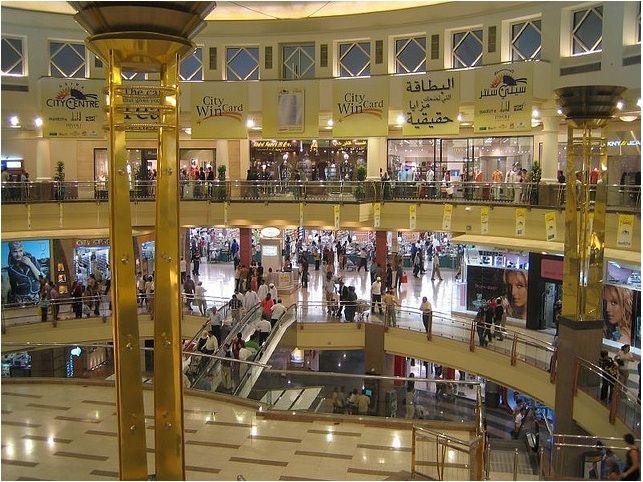

The question of "who might be next" is viewed here with discomfort, even suspicion. The mere hint or suggestion, no matter how hypothetical, raises eyebrows. It is regarded as a "Western question" and is perceived by some as code for cheering on the "democracy wave." Anyone who asks the question is quickly informed about the vast differences that exist between the countries in turmoil and the U.A.E. A key factor is the economy. The level of economic development in the Emirates is far higher than in Tunisia, Egypt or Libya. The earnings of the U.A.E.'s rulers are relatively transparent. The public has not needed to speculate as it had in the cases of Ben Ali and Mubarak.

Furthermore, unlike many of the unresponsive autocratic countries of the Middle East, the U.A.E. is a tribally-based monarchy in which the ruler is obliged to see to the well being of his people. Most U.A.E. citizens have access to government decision-makers. Through the majlis, petitions and complaints are put forward by ordinary Emiratis and often dealt with favorably. This is not to say there are no grievances. For several years now, there has been an underlying sense of dissatisfaction with the large number of expatriates flooding the country, a growing concern over the loss of national identity, and the repercussions of the real estate crash which hammered Dubai not long ago. But overall, the government is perceived as having done a relatively good job dealing with the economic crisis.

Still, Jim Krane, author of The City of Gold: Dubai and the Dream of Capitalism, believes that there are feelings of dissatisfaction amongst a particular segment of the population, especially in the northern emirates.

"There are lots of unemployed Emiratis in Ras Al Khaimah and Sharjah especially, who are becoming second-class citizens in their own country," he said. "There is resentment and potential for protest. However, most are content to pursue their grievances on the individual basis … rather than taking collective action."

Those Emiratis make up 40 percent of the total U.A.E. citizens and a few seem to have picked up on the mood of the moment, according to Al Ain's Abdulla. Their sense of dissatisfaction stems to a certain extent from feelings of envy towards the lifestyle and infrastructure of the more prosperous Emirates of Dubai and Abu Dhabi.

Krane suggests that we should be expecting to see "new subsidies, handouts, pay raises, quotas, especially aimed at nationals. That said, with oil prices at $100 and the U.A.E.'s national population so small, Abu Dhabi will surely be able to spend its way into stability." More importantly, as Krane points out, is "the lack of sectarian tensions in the U.A.E. [which] lessens the cause for worry. Yes, there are Shia in the U.A.E. (somewhere around 15 percent of Dubai nationals), but they are not ostracized as underclasses as they are in Bahrain and Saudi".

What about the youth segment in the U.A.E.? Many are tech savvy and closely followed the events at Tahrir square. The youth were crucial in mounting the effort in Tunisia and Egypt, both of which faced extremely high unemployment rates. The overall unemployment in U.A.E. stands at less than 13 percent, however, and with far more social benefits afforded to its citizens than those of Tunisia and Egypt. Most Emiratis tend to shun the private sector since they view working conditions as not as amenable to their lifestyle as the public sector where hours are shorter and the benefits better. A large part of the unemployed are so by choice as they do not desire to work their way up the ranks and prefer a mid to high-level managerial position from the get go. They would rather refuse a job that they feel is beneath them and instead live off their family support system.

"It is hard to imagine that protests will be mounted given the various options and opportunities afforded to local citizens," said Edward James, Gulf Correspondent at the Middle East Economic Digest.

No worries then? Bahrain seems to be the Gulf's odd man out unless in Saudi Arabia things start turning sour.

Kristian Alexander is Assistant Professor at the College of Arts & Sciences, Zayed University, Abu Dhabi, U.A.E.