Diyrone Solomon, a deputy sheriff in Halifax County, filed for bankruptcy after the hours at his second job tending rental properties were cut when the pandemic hit.

Robin Hullett and her husband, Kevin, a factory worker from Burnsville, filed because steep medical bills kept coming.

Elizabeth McIntosh and her husband, John, filed because his health couldn’t take truck driving anymore — and less money in a safer job couldn’t cover the bills from his heart attack years before.

Solomon, Hullett and McIntosh are among the more than 3,000 people in North Carolina who filed for bankruptcy from April through September. The number is less than before the pandemic, but experts worry it is a brief reprieve from a deluge expected once some federal relief efforts subside.

Since the coronavirus swept through the state in March, federal and local officials have pulled out every stop to prevent economic bleeding. Evictions were postponed. Water wasn’t shut off for unpaid bills. Most foreclosures were delayed.

Still, thousands sought bankruptcy protection. Filings fell about 30% during the pandemic, but a steady stream of bankruptcies kept coming as COVID-19 raged. Extra unemployment benefits, $1,200 checks sent to most Americans, the Paycheck Protection Program — they helped, but the efforts didn’t move the needle on the deeper issues. A decline in filings, though, suggests these measures eased some of the pressure.

When these assists end, experts worry about a wave of filings. The underlying issues that drive bankruptcies, they say, have gotten worse in the pandemic.

“Why are people still filing? People still have debt,” said Robert Lawless, a law professor at the University of Illinois and an expert on consumer bankruptcy.

Health care is still unaffordable for many. Low wage work still can’t cover the expenses of conventional American life such as a car payment and school supplies. Being poor, experts say, is expensive.

The cycles of debt that trap people haven’t relented during the pandemic. In fact, with millions more Americans out of work, bankruptcy lawyers agree that the struggles have worsened. When foreclosures, evictions and other debt collections start again — and some already have — thousands of North Carolinians and hundreds of thousands of Americans will be thrust back into an economic sweatbox.

“It doesn’t matter what the relief packages are now,” said Duke University law professor Sara Greene. “It could be for some people that they really were on the edge of filing. Then COVID-19 comes along and it makes things worse. They were just eking by, COVID-19 came along, and it was just the nail in the coffin.”

A Racial Divide

The pain from these bankruptcies is not equally shared.

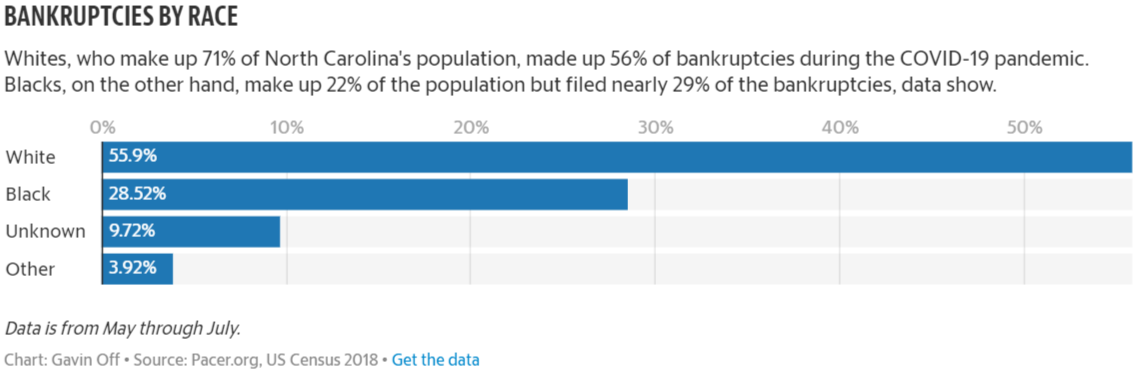

The Charlotte Observer and the North Carolina News Collaborative compiled a database of the 1,760 bankruptcies filed in North Carolina between May 1 and July 31. While bankruptcy filings don’t typically include data on race, the filings were cross referenced with the person’s voter registration, which often includes race. Of the filings examined, 90% of voter registrations included race.

An analysis suggests that in North Carolina, Black residents filed bankruptcy at a rate 50% greater than white residents, a sign of how financial distress can affect communities of color more severely. White people filed for bankruptcy at a rate of 13.28 per 100,000 white residents. Black people filed at a rate of 21.56 per 100,000 Black residents.

The reason Black people filed at a higher rate isn’t immediately clear, although they are over-represented in filings historically. It could hold clues about where the economy is headed, experts said.

“This may be the canary in the mine shaft,” said Bruce Markell, a law professor at Northwestern University and a former federal bankruptcy judge.

While he cautioned that an analysis has yet to be done on the drivers of bankruptcies filed this year, “we know the pandemic hits African-Americans harder, and we know that they lost jobs sooner. The most vulnerable people get hurt the most and they turn to bankruptcy because that’s the only relief they get.”

Other than race, location also skewed filings. Two coastal counties — Tyrrell and Washington — had the highest rate of people declaring bankruptcy. There were more than four bankruptcies for every 10,000 residents in those counties. North Carolina averaged about 1.7 bankruptcies filed for every 10,000 residents.

Mecklenburg County residents filed the most bankruptcies at 154, followed by Wake County at 131 and Guilford County at 108. The figures roughly match up to the population centers of North Carolina. The average age of those who filed was 53.

A Cause and a Catalyst

A bankruptcy filing can be divided into two categories: the cause and the catalyst. People typically don’t file for bankruptcy because they just lost their job. They file because they lost their job and their medical bills keep piling up and their car payment is still due and so is their mortgage. The layered mountain of debt is the cause of the bankruptcy, but a smaller event, such as a pink slip or an emergency room visit, can be the catalyst that pushes someone to file.

“People usually hang on for a while, and try to negotiate with the creditors,” said Karen Moskowitz, director of the consumer protection program at the Charlotte Center for Legal Advocacy. “And then something will send them over the edge.”

For Solomon, the deputy sheriff, his catalyst was lost income. His hours were cut at a second job because of the pandemic. He filed for bankruptcy July 7, listing $52,000 in debt.

The ultimate cause of Solomon’s bankruptcy was the mortgage on his house in Roanoke Rapids. He had missed some payments, and he said he couldn’t work out a forbearance plan with his lender, 21st Mortgage. Solomon needed about $5,000 to catch up on payments. He worked another part-time gig at a funeral home helping run services, but fewer hours with a different job tending rental properties meant he couldn’t come up with the cash fast enough.

Because of the bankruptcy protection, Solomon got to keep his house. “The most important thing was to keep my home,” he said. “Anything else other than that can be recovered, you know.”

Bankruptcy can carry a daunting social stigma, but it is a useful economic tool. If done in a certain manner, the process allows people to wash away thousands of dollars in debt, stay in their homes and restart their lives.

The Financial Sweatbox

Though many filed for bankruptcy during the pandemic, the government’s intervention did help some.

"That stimulus helped us a whole bunch. A tremendous amount," said Robin Hullett, referring to the $1,200 check that the federal government sent out to most Americans. She used it to buy some groceries and pay down some bills.

But bankruptcy was an outcome that a $1,200 check couldn’t stave off. Their debts were unrelenting, Hullett said.

Legal experts call this the sweatbox. It’s the period before bankruptcy where the debts become insurmountable, bankruptcy looms large, and life becomes a fraught mess of calculations.

Roughly half of all people in this pre-bankruptcy period choose to forgo some medical care, according to data from the Consumer Bankruptcy Project, a research project into consumer bankruptcy in the U.S. A quarter go without food sometimes.

The sweatbox meant the Hulletts were eating “ramen noodles and cardboard pizza” most of the time, according to Robin Hullett.

For Robin and her husband, Kevin, the factory worker, their thousands in medical debts put them in the sweatbox. An arm injury has kept Robin from working, but she said she doesn’t qualify for disability. Creditors have hounded them to collect on their debts, some of which were as small as $170. They wanted to protect their single-wide mobile home on a quarter acre in Burnsville. May 19, they filed for bankruptcy.

While medical bankruptcies fueled the passage of the Affordable Care Act a decade ago, the reality on the ground hasn’t changed much. Medical debt is still a top driver of consumer bankruptcies in the U.S. A 2019 study found that about two-thirds of all bankruptcies had the cost of medical care as a factor.

Like the Hulletts, Elizabeth McIntosh and her husband, John, turned to bankruptcy because of medical bills. John was a truck driver, until a blockage in his arteries put him at risk of having a second heart attack, Elizabeth said. For one of his procedures, he was flown to Johnson City, Tennessee, on a helicopter that was not in network for his health insurance. That left an almost $23,000 bill to be paid by the McIntoshes.

John had to give up driving trucks for a job that paid half as much. Still, the helicopter bill needed to be paid. On May 22, they filed for bankruptcy.

“It was what we had to do to keep him off the road and keep him healthy,” Elizabeth McIntosh said.

‘Humiliating’: The Stigma of Bankruptcy

On top of the legal bills, the debt collectors and the damage to a person’s credit, for some, there’s also a tremendous stigma towards bankruptcy. No one wants to go broke.

“It’s very humiliating,” said Robin Hullett, noting she was reluctant to even tell family members because of the shame.

With millions out of work due to the pandemic, Hullett’s situation will become more common, experts said. They expect the number of consumer bankruptcies to rise. Too many people are out of work to keep paying their bills. By how much bankruptcies will increase is still unknown, and can vary widely depending on what aid Congress may supply.

“We’re starting to see people who a year ago were nowhere near bankruptcy, particularly people who had small businesses or good jobs. We’re seeing folks like that start to file,” said Ed Boltz, a bankruptcy attorney in Durham.

After a lull when the pandemic began, new calls to his office started up again in earnest in August when some of the consumer protections started to lapse.

“Cars are being repossessed again. Foreclosures are beginning to start again,” Boltz said.

About a third of workers furloughed when the pandemic hit were eventually laid off, according to one estimate. That’s more medical bills that won’t be paid, more doctor visits put off, and more nights hungry. The bills will pile up, and with it, the need to seek bankruptcy protection.

It can feel like every step forward comes with two steps back, said Solomon, the sheriff’s deputy.

“You think you’ve got a little something saved up over here, then something comes up over here that takes that over there then you start over. You start again and you got a mess over here,” Solomon said. “It seems like it’s always something all the time.”

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill journalism students Elizabeth Moore and Kayla Guilliams, Charlotte Observer data reporter Gavin Off and Bouncing Back project manager Mandy Locke contributed to this report.

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools, and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.