March 17, 2020

It’s the first day of Shelter-in-Place – a complete shutdown of all non-essential San Francisco businesses.

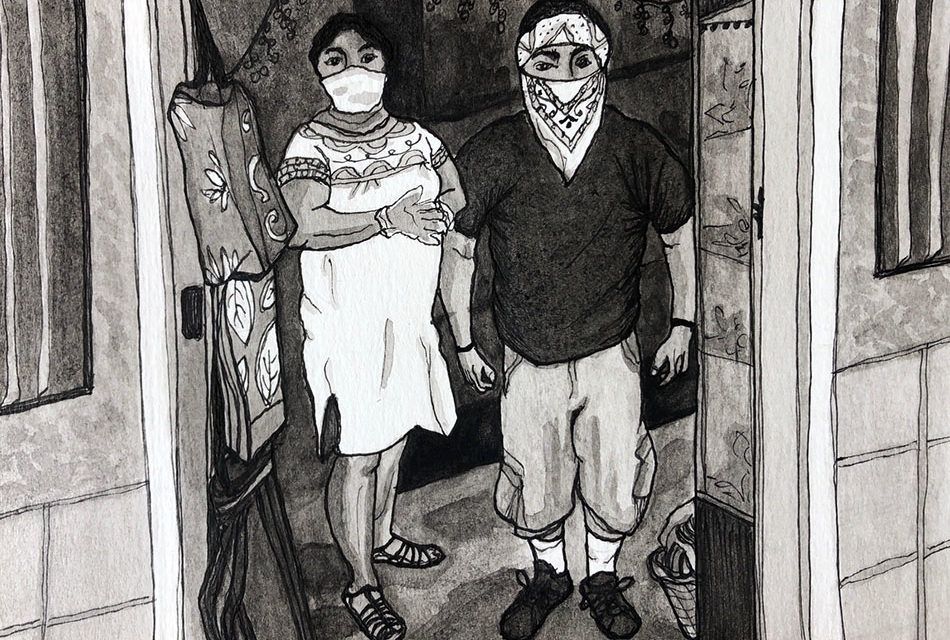

Inside her store filled with Mexican and indigenous craft on 24th Street, Connie Rivera can’t quite bring herself to shut the door and turn the key.

“If we don’t have customers, we don’t have income,” she says, near tears.

She knows what she must do – already most of the lights are off and the sandwich board covered with colorful lucha libre masks has been pulled inside. To close the door behind her, she needs a minute.

She’s trying to absorb what the pandemic will mean for the two stores that she owns with her husband, Ricardo Peña: Mixcoatl, which opened in 2004 and where she now stands behind the counter, and Colibri Corazón de la Misión, which opened in September 2017 just five blocks east to sell crafts and clothing.

As with many immigrants, the stores represent the physical proof of her family’s success: the start-up funds they needed, earned at multiple odd jobs, markets and from Ricardo’s house painting business.

The stores also offer Connie and Ricardo a way to share their culture. Over the years, their customers have been blessed by visiting shamans and entertained by musicians and artists.

"Apart from my family, it signifies a lot,” Connie told Mission Local in 2018. “because for me, it’s very important to maintain our traditions and represent the culture… to keep alive the traditions, the art … It’s important to maintain and know it, but to support it.”

“It’s mi vida, my life,” she said then.

On March 17, that life felt like it could be over.

“It is just hard. We weren’t prepared for this,” she says in tears. “I am trying to not think too much, but I am really thinking all the time. Food for our family is a priority now, but to have food, we have to have sales. It just feels like a big dark storm.”

Late March

Even now, to spend time around Connie and Ricardo is to be in a very good place. They are intelligent and thoughtful – Connie full of energy with entrepreneurial zeal and Ricardo, quiet with a wry sense of humor. I first met Ricardo in 1998 when I was looking for a house painter and he came to bid on the job.

Twenty years later, he told me that was the job that allowed him to start his own business and go from being an employee to a boss – his own boss because Ricardo is meticulous, and he prefers working alone.

The two met in Mexico and when Connie came north, Ricardo, smitten, followed. It’s a marriage that clearly works. They tease one another, listen closely when the other is speaking and share a belief in education and community. Both are fluent in English and Connie has also picked up some French so that she can speak with the summer tourists from France.

Xochi, their 20-year-old daughter, is working at a coffee shop and going to college, and Cuauhtémoc, their 12-year-old son, is doing his schoolwork online.

Cuauhtémoc, says Connie, has exactly what he has always longed for – “his parents at home and me cooking.”

In the past, Connie says, Ricardo warned her about being too focused on the business and making money. Building community was a greater priority for him. “I didn’t always think he was right," she says. “But he was.”

Years of being part of an Aztec dance group and connecting with friends and old clients have resulted in unexpected forms of support. A check arrived from a customer for whom Ricardo often does painting jobs. So did orders for elaborate ankle bracelets that Ricardo’s Aztec dancing group needed. “We’re always too busy,” he said. For once, they have plenty of time.

“You’re not alone in this,” friends tell Connie.

Early on, to make their resources last, Connie and Ricardo joined thousands of others in the Mission to pick up a weekly box of food staples.

“It helps a lot,” she says.

Soon they were both volunteering at one of the lines, Connie going early in the morning and Ricardo arriving later so that one of them is always home with their son.

Early April

UCSF and the city’s Department of Public Health have announced a major testing campaign in a census tract that includes Connie and Ricardo’s family.

When I run into Connie, she’s skeptical and suspicious: Why in the Mission? Are they going to use big needles? We’ve been sheltering in place all this time and now they want us to go out and get tested, won’t we be exposing ourselves? She says Mission Local should write a piece answering some of these questions. We’re getting similar queries from our monolingual Spanish speakers on our text service.

We publish a Q&A but we know not enough people will see it on our site, so we print 1,000 bilingual flyers and Connie and Ricardo offer to help distribute them door to door. Although she’s the instigator of the article, Connie remains circumspect. She simply doesn’t want to expose her family any more than is necessary.

Even her own internal pressure to reopen has subsided. “We definitely need the money,” she says. “But we’re not going to be rushing to re-open.”

Adds Ricardo, “We follow the news, and thousands of people are dying every day. We don’t want that. It doesn’t make sense to open right now.”

But Connie also wonders how many stores will even be around to reopen. One craft store down the block has shut down for good. Her landlords have been patient and she’s applying for small loans and grants, but so far nothing has come through.

The pandemic has its own timetable. Connie and Ricardo understand they must adapt to it.

When she’s not cooking, Connie is finally able to tackle projects at home, organizing their small space and creating storage. “We always wanted time – both of us,” she says.

Ricardo relieves stress with frequent dog walks. “He spends more time with that dog,” she says teasingly.

He also joins a small group of dancers occasionally in a nearby park to perform dances – socially distanced from one another. Aztec dancing is a part of their culture that Connie and Ricardo have shared with the Mission for years – teaching classes, and performing – but it is also a spiritual practice, one Ricardo is happy to perform with no audience except the other dancers.

May

Two-and-a-half months into the lockdown, Connie is having one of those days where the virus seems to have gotten the better of her. “It’s been hard inside the home,” she says. ”I don’t want to use the word depressed. It’s hard to think how we’re going to survive.”

Even her son, she says, is “dreaming about going back to normal.”

She knows her landlords can’t be patient forever. There is talk of re-opening, but she wonders whether customers will return. “I worry once we’re open how we are going to bring in people.” She relies a lot on foreign tourists and major summer traveling seems unlikely.

But she’s an optimist. To prepare for reopening and meet the demand for masks everybody is wearing, she has already placed an order for hand-embroidered masks from her extended family in Mexico. So when the mayor announces that stores can offer curbside service starting May 18th, Connie has her masks and incense at the door of Mixcoatl. She can’t yet imagine opening Colibri.

On the weekend of the 23rd, I stop by to say hello. “It’s okay,” Ricardo says about the business, but nothing like it would have been had Carnaval not been canceled.

He supports that decision – Canaval brings in crowds that are far too risky during a pandemic – but the shop missed out on Mother’s Day business too and in another month it will miss Pride Week. These celebrations bring thousands of visitors into the city and many into their store. That won’t happen this year, and the hard economic realities of operating a business in a pandemic are starting to sink in.

June

Connie and Ricardo have a decision to make. The landlord for Colibri, their second store, had been patient with them, but he’s lost another paying tenant and he’s worried. Their lease is up, and he wonders if they want to renew it or let it go. If the landlord takes the deposit they put down when they first leased the space in 2017, they won’t owe him anymore.

Already, they are letting customers into Mixcoalt but doing so requires a lot of attention. Connie trails behind them, wiping down surfaces as she talks to me about their decision.

She still can’t imagine re-opening Colibri, but she and her husband have a strong emotional attachment to the store. They put a lot of effort into painting and fixing up the space. It is hard to let it go.

It is becoming clear, however, that even if they are able to bridge one or two months with a loan, it will be longer before they can cover the rent through sales.

“I guess it is realistic,” she says about closing Colibri, but realism does not feel particularly good right now.

This is the first of several installments following the story of one Mission business. In the last week, one of their friends started a GoFundMe Campaign for Connie and Ricardo.