On a warm January afternoon in southern Ethiopia, thousands of ill-tempered livestock stand in groups with the pastoralists who have guided them for dozens of miles to drink. The animals dot an expansive field of Acacia trees, severed bits and pieces of dead grass and dust.

Earlier in the day thousands of young goats, sheep and calves took turns to have their fill of water. And the show will not end with the cattle; camels are still waiting in line. For being the best able to resist drought, now they will be last.

As the sun beats down, a human chain of water fetchers forms a line down the gullies and sings work songs to help keep rhythm during the backbreaking work of drawing water from the wells and delivering it to the troughs on the surface — sometimes from a depth of about 160 feet. This cluster of "singing wells," along with a mechanical well built by the Ethiopian government, are the only things standing between the thousands of animals here and death. Still, this is only the wind before the storm as the animals have to endure three more months of unprecedented drought before the rainy season begins.

"They [the animals] are starting to die in many places. We have nothing to feed them on," says Galgalo Dida, a deputy chief in the area. "We are in critical fear now. We have a big problem," he adds, as he shifts his glance, slowly regarding the other men around him and the kids who hang on to their clothes.

For the pastoralists here, animals are their only livelihood, as they have been for countless generations. A Borena man in this area will own anywhere between 20 and 1,000 animals.

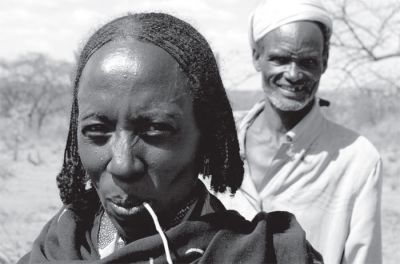

Concerns are also growing further south in the Somali region of Ethiopia where Mohammed Hassan, the sultan of Gare, says the situation is equally dire. Hassan, a tall, middle-aged man sporting an orange-colored beard, speaks calmly and with little emotion about his region's shifting weather patterns.

"Now the annual rainfall is decreasing," Hassan says. "Due to this situation, a number of water points are drying, even springs are drying out."

DIGGING DEEPER

The declining water resources mean more work for the community, which has to pursue the water further into the ground." We are experiencing drying wells and reduction in water volume of big rivers like Dawa. Now we have to dig more to get water," he says, scooping into the air with his hands.

As the traditional leader for more than 476,000 Gare people, a clan that spreads across Ethiopia, Kenya and Somalia, Hassan is knowledgeable about issues affecting his people and knows better than to place all the blame on outside forces.

The increase in the number of people and their livestock and the accompanying deforestation that his area has seen in recent decades could have contributed to the worsening drought, Hassan says.

Hassan, however, does not have answers to some of the changes, like the rise in temperatures experienced here in the last few years.

At Leh, one of the villages under Hassan's command, the story is similar. Drawing water from their traditional wells, young men sing to their livestock: "Have it, this is the water. If you refuse, it is up to you."

The wells at Leh, says Ibrahim Ganamo, the chief of the area, were dug by their ancestors 300 to 400 years ago. Now they are disappearing at alarming rates. In just a few years, nine have been covered by sand due to erosion. The village has no means of reclaiming them, he says.

While Ganamo can explain some of the locally inflicted environmental calamities such as soil erosion, there are other trends that seem beyond explanation to him. Rains have dwindled and temperatures have gone up in the recent past.

"Last year it rained for only two days," he declares, lifting two fingers in the air and shaking his head in despair.

Statistics are hard to come by here, but Ganamo says. "Last year alone people here lost 80 of every 100 animals they had."

It is a dangerous phenomenon that can wipe out a community.

"If the animals die," he says as his eyes follow the galloping cattle, "people will also die."

AFRICA PAYS THE PRICE

The plight of Ethiopia's pastoralists reflects concerns raised in the landmark 2007 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which forecasts that Africa would be the continent placed at greatest risk by global warming.

"Although Africa, of all the major world regions, has contributed the least to potential climate change because of its low per capita fossil energy use and hence low greenhouse gas emissions, it is the most vulnerable continent to climate change because widespread poverty limits capabilities to adapt," the report noted.

Negusu Aklilu, director of the Forum for the Environment in Ethiopia, cautions against blaming the victims of global warming.

"Is it because we Africans are irresponsible? Is it because we are careless? No. It is because people are poor. We are dependent on natural resources."

The difference, Aklilu says, is that the poor misappropriate resources for survival, the rich misappropriate resources for luxury.

According to the U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, half of the 314 million Africans who live on less than $1 a day in Africa are highly dependent upon livestock for their livelihoods, and 80 percent of those people live in pastoral areas.

"In Ethiopia and larger parts of Africa we are going to be the most vulnerable, the hardest hit," Aklilu says.

RESOURCE WARS

And strained natural resources inevitably lead to strained relations between communities that are competing for the same dwindling supply of water and pasture land.

In June 2006, open conflict erupted in the Borena zone in southern Ethiopia between the Borena and the Guji when the Guji laid claim to land that had long belonged to the Borena. Hundreds were killed and 23,000 people were forced to flee. Intermittent fighting has continued since then.

For Habiba Guto, 32, the conflict has been disastrous. A mother of seven, she had managed to save enough money to open a small store selling basic provisions to the Guji and the Borena in the town of Dawa.

But when conflict broke out between the two groups, Habiba lost everything she had but her children. She counted 26 bodies of her dead fellow Borenas including her brother-in-law.

She moved to the town of Negele to stay with her extended family and has never looked back. She lives a day at a time, begging for food to keep herself and her children alive.

According to a February 2008 report on conflict analysis by Nega Emiru, a program officer for Care International in Ethiopia, the rising conflict in the region is part of the intensifying conflicts involving the pastoralists' communities in the Horn of Africa.

"Recurrent droughts and worsening climatic conditions are fueling resource-based conflicts between the pastoralists," Nega notes.

These conflicts in turn are made worse by the widespread availability of automatic weapons.

Abdulqadir Abdii, the chief government administrator for the Borena zone, says the people of the region acquired large numbers of automatic weapons after they were smuggled out of government armories following the downfall of the socialist regime of Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1991.

Weapons have also been obtained from on-going regional conflicts in Somalia and Sudan.

LOOKING FOR SOLUTIONS

As conflicts soar, nongovernmental organizations and the elders of various communities are looking to proactively solve problems.

Hassan says that his leadership is organizing ways for people to try helping themselves by educating them to combine the traditional ways of livestock farming with some modern farming systems.

Also, Hassan and his council have worked to sensitize the community to deforestation. Through better management of resources, conflict can be reduced, Hassan says.

In the same vein, councils have formed to help resolve conflict.

"The council wants to return to the traditional ways of conflict resolution," Hassan says.

Such traditional ways of conflict resolution involve elders from groups in conflict holding meetings to determine what punishment should be meted out to or what fines should be paid by people who start or instigate conflict, Hassan says. The leaders also discuss ways of preventing future conflicts, he adds.

While the pastoral communities try to adapt to the changes forced on them, they can only wait and see if the wealthy nations that largely created the climate crisis will take actions to reverse the situation.

But the rich world should read the writing on the wall: what is transpiring here may befall them in a few years, Aklilu says.

"What is happening in Africa today is a warning to the world. We do not have to ask whether climate change is happening," Aklilu says. "Climate change is real."