Check back on the Nature website for regular updates to this diary.

17 DECEMBER 2014: TERRIBLE REALITY

When Ebola first hit Sierra Leone, 21-year-old Mohammed Nao didn’t believe that it was real. There were so many rumours — that the epidemic was a hoax designed to get international donor money, or to kill off members of rival political factions. “Have you ever seen an Ebola patient?” he would ask his friends.

That changed in September, after a friend’s grandfather got sick. Nao helped to care for the man as his condition deteriorated, and he began vomiting, having diarrhea and hiccuping. Friends and neighbours suggested that the man might have Ebola, but his wife refused to allow her husband to be taken to the hospital. Instead, she called an herbalist, a traditional healer who told the family that the man had been shot by a witch gun — a spiritual weapon that rains calamity on the victim.

The healer extracted some small stones from the grandfather, which he said were bullets from the witch gun. He told the man’s family that he couldn’t remove all the bullets and would come back later that night.

That would be too late: the man died a few hours later. Nao helped to prepare the body for burial. A few days later, Nao, his girlfriend and their one-month-old son began to feel unwell, along with five others. By then, no one denied that Ebola might be the cause of their illness.

Nao and his girlfriend checked themselves into a holding centre in Freetown — a facility where patients wait for Ebola test results. They were lying in beds next to the dead man’s wife when she died.

Nao was transferred to a hospital, where the other patients called him “Chairman,” because he advocated on their behalf: “I say, doctor, we are not having enough food, enough water, enough medication,” he remembers.

He and his girlfriend survived, and they left a treatment centre in Freetown on 5 October. Nao credits his survival to reporting early to the hospital, good food and medicine, and prayers from his family. But his baby son, along with four others from his girlfriend’s house, died of Ebola.

Now, sitting on the front porch of his uncle’s house, where he lives on a hillside in Freetown, Nao wears a shirt with an Ebola prevention message. There is no question of whether he believes Ebola is real any more.

17 DECEMBER 2014: CULTURAL CHALLENGES

Nature reporter Erika Check Hayden travels to Sierra Leone to meet the officials fighting the spread of Ebola.

Read Erika's print story in the 18-25 December issue of Nature: Inside the cultural struggle to stamp out Ebola. From the story:

Yeli Sanda, a village just a few kilometres outside the district’s capital city of Makeni, was the first place to be hit. Over the following months, more than 40 people in the settlement of about 700 became infected; 22 died. In November, the virus infected a woman in Tambiama, about 11 km up the road. A friend who visited her acquired the virus and carried it another 1.5 km to the village of Mayata. She and at least five others there have died.

But just a few hundred metres from Yeli Sanda, the village of Yoni has not seen a single case of Ebola. As soon as the village chief learned that Ebola had struck, he forbade his citizens from visiting Yeli Sanda or attending burials of its residents. His swift action has kept the 100 people of Yoni healthy while other communities have been devastated.

11 DECEMBER 2014: FAR TO GO

Red dust billows up under a United Nations helicopter as a pilot lowers the craft to a field in Bo, in central Sierra Leone. Moments after the chopper touches down, Alie Brime Tia from the country’s ministry of health disembarks with precious cargo: 17 patient samples for Ebola testing, packed into red coolers sealed with tape.

Moments later, epidemiologist Dianna Blau of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) loads the coolers into a waiting sport-utility vehicle, then whisks them away to a makeshift laboratory. The Bo facility one of six that have been set up in Sierra Leone by foreign groups to perform tests to diagnose Ebola; three more should be coming on line in the next few days.

The tests determine whether patients suspected of having Ebola — who wait in holding centres until they are tested – are sent back home, or onward to a treatment centre. Time is of the essence: if a patient tests negative for Ebola, staying in a holding centre increases her risk of becoming infected; if she tests positive, she needs care. That’s why the CDC is using a helicopter to fly in samples from faraway cities that lack their own labs.

“With Ebola, a one day delay can kill you,” says Nick Wagar, a molecular biologist with the CDC who is coordinating countrywide diagnostic testing in Sierra Leone.

The helicopter began the day’s journey in Freetown, in the west. The landscape changes from flat rivers and marshes to mountains, jungle and hills the farther north and east we go. Tin roofs on the houses glint in the sun as we fly over the occasional village. We’re heading to places that are hundreds of miles from the nearest diagnostic lab. On days when the helicopter doesn’t come to these sites, samples are driven out by ambulance to Bo — an hours-long journey over pothole-filled roads.

A day's journey

Our first stop is Makeni, on the same day that Public Health England is opening a lab in the district that will soon take over testing here.

Next is a tiny village in Koinadugu, where the helicopter lands by a cluster of tents on a field hacked out from the jungle. The outbreak here has been subsiding in recent weeks, and when we touch down, a doctor with the aid group Medicos del Mundo says that only one patient remains in the village’s community-care centre.

“It’s good,” he says with a sweaty smile. “We’re happy.” With the local outbreak waning, there may not be a need for these helicopter flights much longer.

The team's third stop is Bo. There, CDC virologists Aridth Gibbons and Christin Goodman duck into a wood-framed shack with white-tarped walls and change into protective gear, including gowns, gloves, and respirators. They spend the next two hours transferring blood samples from the patients in Makeni and the Koinadugu village into test tubes containing chemicals that rendering any viruses harmless. It’s hot and sweaty work, done outside in tropical heat and full protective equipment.

Other scientists then extract RNA — the genetic material that the Ebola virus uses to make more copies of itself — from the processed blood samples. The workers then perform a test called polymerase chain reaction, amplifying the genetic material in the samples and looking for genes that are part of the Ebola virus. CDC scientists check for two separate Ebola genes; if they find them, the sample is positive for Ebola.

This lab has tested more than 7,000 samples since August. Only a small portion of each sample is used for testing; the rest is stored in a freezer, which is connected to a generator. Scientists elsewhere have been clamoring for access to samples like these, and they may soon get it.

Blau’s team hopes to send the samples to CDC headquarters in Atlanta, Georgia, on 12 December, via a chartered flight.From there, the samples could be used for research — for instance, on further analyses of the genetic changes that are accumulating in the Ebola Zaire species of the virus that is causing this outbreak.

But for now, there is plenty of work to be done here to help stop this outbreak. On this day, the CDC team here will test 132 patient samples. Virologist Mike Flint points to the tile floor of the lab in Bo: “For us, the priority is this,” he says.

7 DECEMBER 2014: IN QUARANTINE

When we arrive at the school in the village of Tambiama, a few people stand in a dirt yard behind a strip of red and white quarantine tape.

Then, as a policeman and a soldier call to the rest, men, women, and children slowly file out — more than 40 people altogether. We’re here, in northern Sierra Leone, to meet with the friends and neighbours of a woman from Tambiama who died from Ebola on 14 November.

Today, when a local priest asks them how they feel, the villagers all say that they are fine; a few even break into a spontaneous dance to prove how healthy they are. If all goes well, they will be released from quarantine in a matter of days.

But for the moment, they have little to do. Asked how they feel about being in quarantine, the villagers murmur with dissatisfaction. James Koroma, a former teacher at the primary school, gestures to the village outside the quarantine tape, where people’s own houses are now off limits to them. Though I don’t speak his language, his meaning is clear: we don’t like being stuck in here.

Shekub Mansary, whose job is to trace contacts of people infected with Ebola, translates for Koroma: “They are not feeling good,” Mansary says. “They are not feeling good at all — there [is] no free movement for them.”

Quarantines have been a widely deployed tool in this outbreak, but they are a crude one, and it’s not clear how effective they have been.

Checkpoints line the road from the capital of Sierra Leone, Freetown, to Makeni, the big city near Tambiama. At every one, workers examine travellers for fevers.

Bombali district, which includes Tambiama, has been under quarantine since September. Only vehicles with special permissions can enter and leave. But there have been 877 Ebola cases reported here over the course of the outbreak, and one recent day — 6 December — saw 11 new cases.

And though 1 million Sierra Leoneans now live in quarantined districts, that hasn’t stopped Ebola from traveling down roads and highways to infect new areas. People resent the quarantines, and sometimes resist them: residents of a village down the road from Tambiama fought off quarantine officers with machetes a few weeks ago.

Catherine Bolten, an anthropologist at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, who has studied the ethnic history of the area, says it’s not hard to understand why people resist the quarantines — especially since there were problems early on guaranteeing that quarantined families got enough to eat.

“That’s a reasonable response under those conditions,” Bolten says. “You might or might not get Ebola, but you’d definitely know if you’re starving to death.”

3 DECEMBER: CLOSE TO HOME

“From the back, from the back!” shouts Halima Shyllon, the nurse matron of a newly opened Ebola treatment centre in Makeni. She and two workers are supervising doctor Moges Tadesse as he removes the hooded Tyvek suit that he’s been wearing to treat sick patients for the past hour.

Tadesse, standing in a bucket of bleach, pulls off the suit; his green scrubs underneath are drenched in sweat. Shyllon murmurs approval: “Good,” she says.

When it opened on 24 November, this treatment centre became the district’s first. Before, patients were sent elsewhere in the country, wherever there was a bed available. The prospect of being sent far away from their families — to cities such as Kenema, roughly 150 kilometres away — dissuaded people from reporting for treatment. The fear was well-founded: families often never saw or heard from such patients again, since many died in remote care facilities.

Now, families can follow the ambulance as it delivers the sick here. It’s hoped that this will convince more of those infected with Ebola to report for care earlier, while they have a better chance of surviving.

This centre is run by the African Union and largely staffed by Africans: Shyllon works for Sierra Leone’s Ministry of Health, Tadesse is Ethiopian. There are Ugandan doctors on site and Nigerians arriving soon. There are 54 patients here today and room for 46 more.

One of those patients, Usman Fofanah, was so sick when he arrived here a few days ago that he doesn’t remember the journey from Port Loko, about 80 kilometres away. He had diarrhea, vomiting and pain in his feet and knees. He has lost his grandmother, an aunt and two sisters to Ebola. Still, today, Fofanah is smiling and feels much better — well enough to walk around the “dry” section of the treatment centre. And yesterday, he was able to speak by phone to his mother, who had feared that he had died.

If Fofanah continues to improve, Shyllon and her staff will test his blood to find out whether it is free of Ebola virus; only then will Fofanah know if he’s been cured.

2 DECEMBER 2014: THE TREATMENT GAP

In some ways life goes on as usual in northern Sierra Leone, despite the Ebola crisis. People in roadside villages between Freetown and Makeni, two current focal points of the epidemic, continue to gather around village water pumps, braid each other’s hair, wash their clothes in the river and hang them out to dry in front of mud-walled houses.

But it’s impossible to avoid the fact of the outbreak for long. Every few miles police or soldiers stop traffic at checkpoints and take each traveller’s temperature. People file out of minibuses, line up for officials wielding thermometers, and reboard their vehicles on the other side of the cordon. Posters describing the signs and symptoms of Ebola are pasted up on buildings and houses; schools are empty, their gates closed and classes cancelled.

Then there are the clusters of white tents that rise at certain points along the road. Some, surrounded by mud walls, are community care centres — holding places for those suspected of having Ebola. Others, set farther apart from the villages, along large gravel roads, are treatment centres enclosed by chain-link fences.

One treatment facility, outside the city of Lunsar, sits near a fork in the road; the western branch leads to Port Loko, where Ebola transmission “remains persistent and intense”, the World Health Organization said on 26 November. (Seventy-two new Ebola cases were reported in Port Loko during the week ending on 23 November, according to the WHO.)

The treatment centre near Lunsar is run by the International Medical Corps and opened just two days ago; yesterday, six patients arrived. But there still are not enough treatment facilities for everyone who needs them in Sierra Leone. Although foreign governments, including the United Kingdom and China, have committed to construct new treatment centres in the country, progress is slow. Just 11 of the 700 additional treatment beds pledged by the United Kingdom in September were operational as of 27 November, the charity Médecins Sans Frontières reported today.

Tomorrow, I’ll be visiting a town hit hard by Ebola to see how communities are coping with this lack of resources.

1 DECEMBER 2014: MIXED SIGNALS

Arriving at an Ebola treatment centre outside Sierra Leone’s capital, Freetown, I heard celebratory voices singing and clapping: three survivors of the disease were preparing to leave. Staff at the centre in Kerry Town, which is run by the non-profit group Save the Children, presented the survivors with laminated certificates documenting their Ebola-free status. The patients looked wearied by their fight with Ebola, but they were going home.

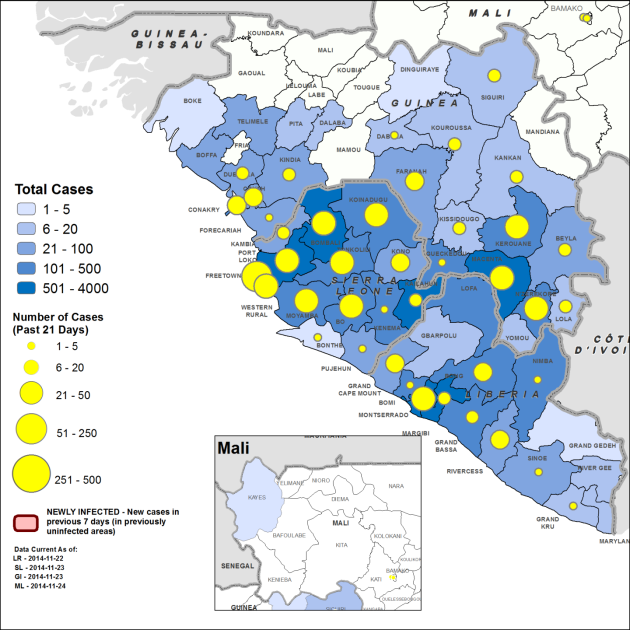

As the ongoing Ebola outbreak approaches the one-year mark, there are signs of hope — such as these survivors. And the epidemic, which has claimed upwards of 5,600 lives, is finally stabilizing in Guinea, Liberia and parts of Sierra Leone, according to the World Health Organization. Health officials are congratulating themselves: “The global response has successfully turned this crisis around,” Anthony Banbury, head of the United Nations Mission for Emergency Ebola Response, told a press conference in Freetown today.

But the number of cases is still rising in some areas in Sierra Leone, including Freetown, and there are still not enough treatment beds for everyone who needs them in this country. Sierra Leone is still seeing hundreds of new cases a week; 385 were reported in the week ending 23 November, WHO says. And although the three survivors left the treatment centre in Kerry Town today, 20 Ebola patients stayed behind.

There’s no one reason why the epidemic is still growing in parts of Sierra Leone, but a contributing factor is the difficulty of convincing people who have never experienced the disease to change the way that they live their lives, care for the sick and bury the dead.

I’ve traveled to Sierra Leone to see how these factors are playing out on the ground — and what that means for the broader Ebola response.