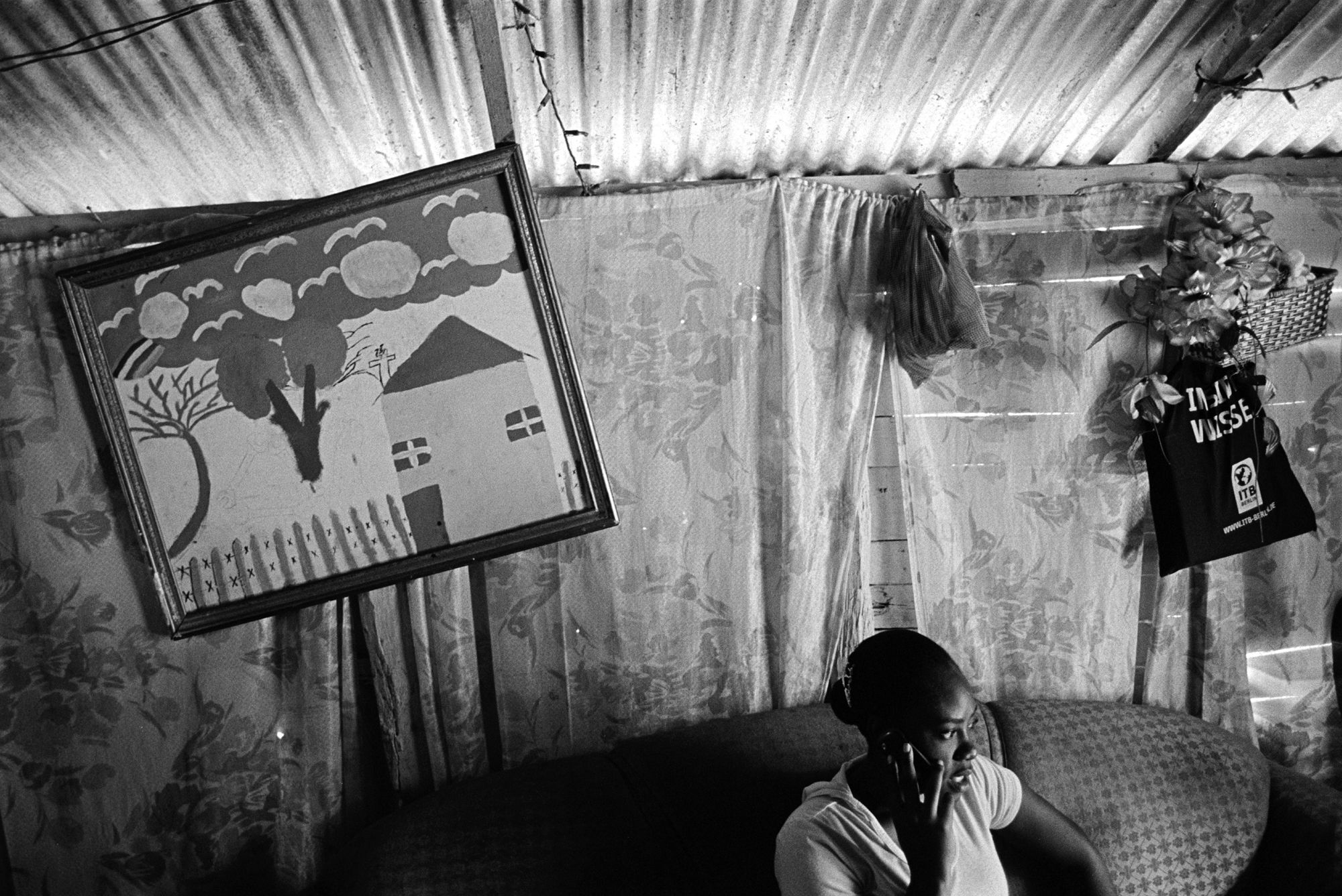

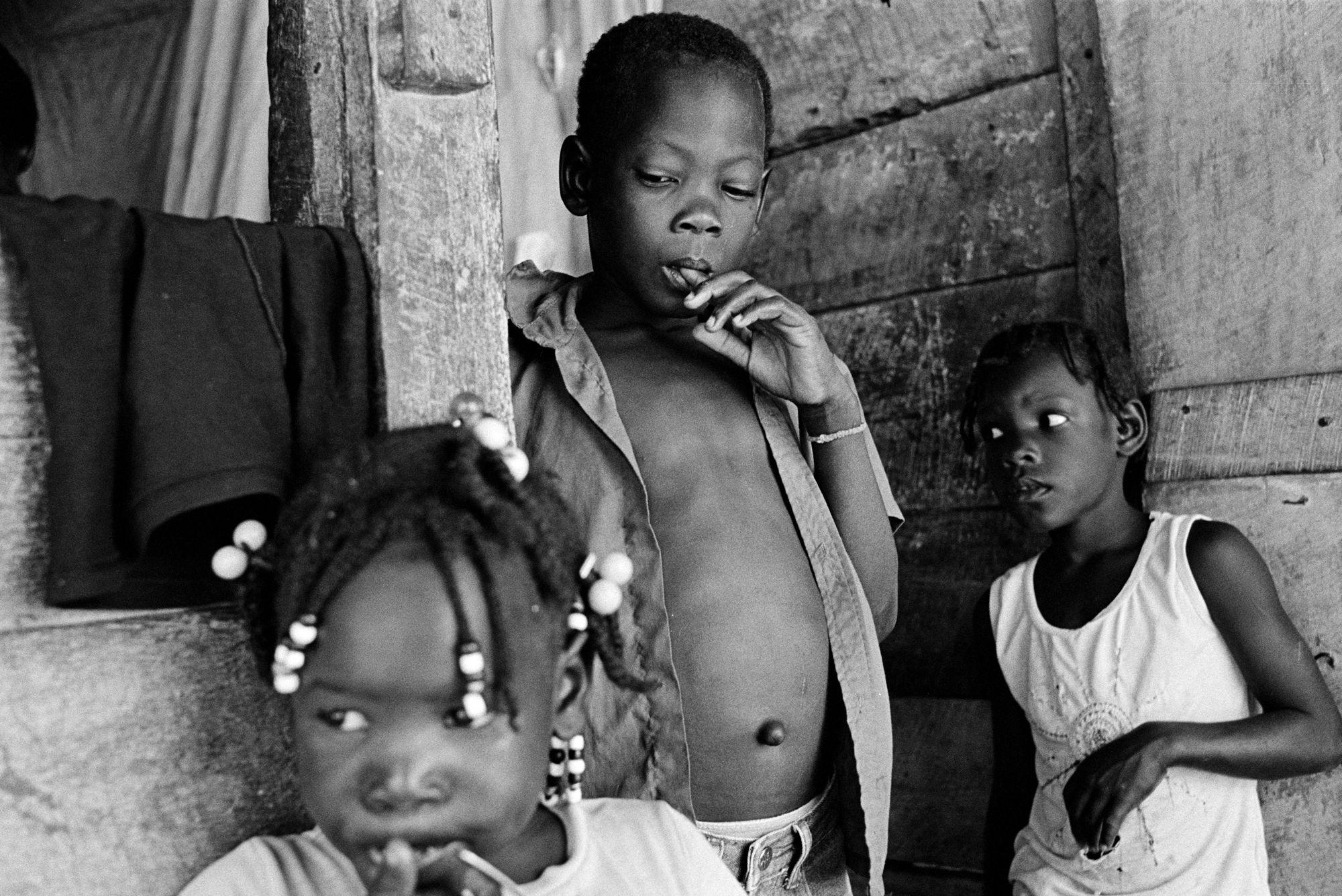

Ethnic Haitians have played a vital role in the development of the Dominican Republic. Haitians have been the backbone of the sugar industry, working as braceros or cane-cutters, and in recent years they have made invaluable contributions to the construction and service industry. But deep-rooted racism and discrimination towards people of Haitian origin have been a part of society in the Dominican Republic since the late 1920s.

It is estimated that between 500,000 and one million people of Haitian ancestry currently live in the Dominican Republic, including tens of thousands of children and young adults who were born in the country. Yet changes to migration laws in 2004, governmental directives in 2007, and a change in the Constitution of the Dominican Republic in 2010 have denied or retroactively stripped Dominican citizenship away from tens of thousands of Dominico-Haitian youth. Human rights groups see these legal and policy changes as specifically targeting those of Haitian descent. As a result, these residents find themselves unable to access opportunities afforded to other Dominican citizens, such as legal employment, access to social services, or the right continue their education and to legally marry.

While the situation in the Dominican Republic has now gained the attention of the Inter-American courts and international human rights organizations, it remains the largest case of statelessness in the Western hemisphere.

This slideshow was also featured on The Atlantic