Pakistan—a country with more than 170 million people and a deteriorating economy—has been in the eye of the storm since its inception in 1947. Democracy and development are two sham words when one looks at its turbulent history—frequent military coups and violations of basic human rights at the hands of security agencies and armed groups.

Voices of dissent are most often silenced and forgotten in Pakistan’s power corridors, which are dominated by military generals, landed aristocrats, industrialists and religious leaders. Practically, in their view, you have to maintain the ‘status quo.’

First they threaten you, and if you don’t follow the line there is every possibility that you will be abducted and then killed in cold blood. This is especially the case for journalists. You don’t know when your reports annoy a militant or criminal group—or make you the target of security agencies that want to shape the course of history according to their own whims.

The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) reports that 51 journalists and two media workers have been killed in Pakistan since 1992.

The region most affected, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province and Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) along the Pak-Afghan border, is in the grip of unprecedented violence and religious terrorism.

In May 2011 I traveled to Pakistan under a fellowship from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting on a month-long reporting trip. As I reached Peshawar, a colleague informed me that Nasrullah Khan Afridi, a journalist from Khyber tribal agency, had been killed when an explosive device ripped through his car. Afridi was a courageous soul who exposed the brutalities of a militant group on the Pak-Afghan border.

I received the news with deep shock as I knew Afridi as a journalist for the last five years. In 2007 he moved his family to Hayatabad, a posh area in Peshawar, after the militants threatened him. On several occasions he informed his colleagues that a militant commander wanted him either to leave the area or face his wrath. He shifted his family to a relatively safe place but still he was not spared.

From Waziristan to Swat Valley journalists have to make choices about what to report and what topics should be avoided. It becomes more challenging when the two sides of the conflict—the Taliban and the security forces—want their own version of the story and as a journalist you have to uphold journalistic values of objectivity and impartiality. The journalists are not provided the freedom and protection to report on the conflict as it is unfolding—that’s why there is so much confusion and uncertainty in the Pak-Afghan region after a decade-long war against terrorism and the sacrifices of thousands of innocent people.

In 2009 Pakistan deployed 25,000 security forces in Swat Valley to fight against the militants of Taliban commander Fazlullah. About 2.5 million people were displaced by the military operation. However, in a time when it was very important that the public should be informed and updated about the progress of the fighting, all the journalists including me were asked to leave the area. I wondered why, if the Pakistan Army really wanted to eradicate the menace of terrorism, it was so opposed to the presence of journalists in the region. In the early days of the military action Inter Services Public Relations (ISPR) of Pakistan Army was the only source of information on the conflict. It issued press releases about the number of militants killed in the operation with no mention of the civilian casualties and destruction of public property.

This summer when I visited Swat Valley I hoped journalists would be able to report the truth about the emergence of religious militancy and outcomes of the military action:

- When and how Taliban chief Fazlullah escaped when there was military presence in almost every nook and corner of the valley?

- Why the security forces failed to protect the houses and properties of the people when they left their homes on a short notice?

- What hinders the security establishment to expose security personnel responsible for extra-judicial killings in the valley?

- Why the reconstruction and rehabilitation process is so dismally slow and where the aid money is being spent?

- If the military action is a success then why are political activists and civil society workers being killed with impunity?

- What action is being taken against the officials and religious groups who allegedly supported the spread of Talibanization in the valley?

There are so many important questions that need to be addressed.

During my trip I visited office of a daily newspaper to meet some friends. What I witnessed was a shock: a senior military official dictating news to the journalists working there.

I recalled the period before the launch of military operations when statements and interviews of Taliban commanders and so-called spokesmen of Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) were published on the front pages of the local dailies and given much space in news bulletins and talks shows on the TV channels.

At that time a senior journalist in Mingora told me if he failed to give more coverage to Taliban they would dub him as an American spy and would cut his throat.

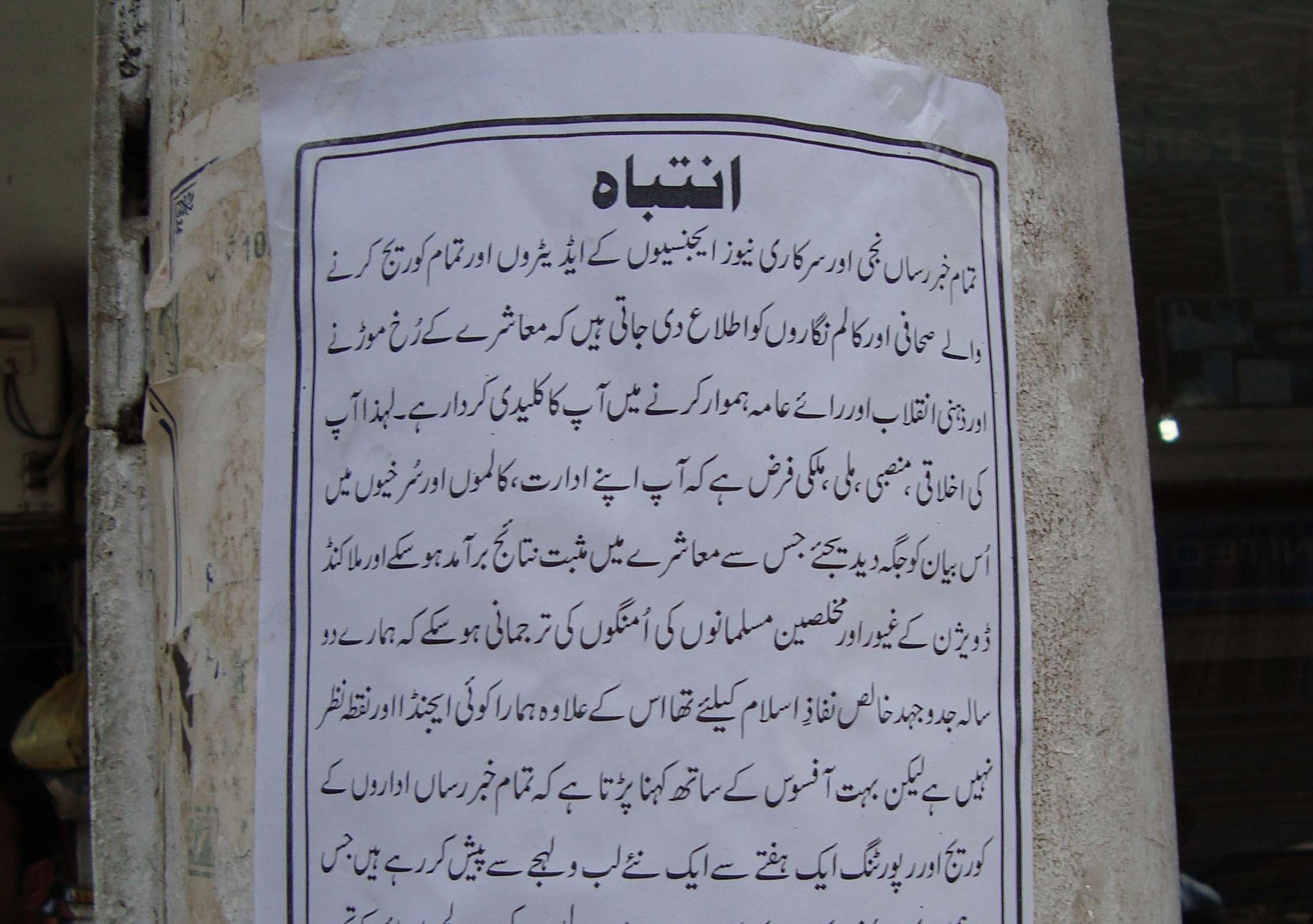

Where are the public voices? Where are the stories of the people who lost everything that they had in this conflict? Where does our journalism stand? And what a serious dilemma is this when free flow of information has become a crime? When I walked out of the office I saw a poster commemorating the sacrifices of journalists who laid their lives in the line of duty during the conflict. I saw the photo of my friend Qari Shoib, who was killed in 2008 –in the view of many, by security forces—while returning in his car from a local hospital with his ailing daughter.

I also spot the photo of Musa Khankhel a journalist for a private TV channel who was killed by armed men in 2009 when he was covering a peace rally organized by chief of the movement for the enforcement of Shariah (TNSM) in Matta town of Upper Swat. There are journalists who were killed in bomb attacks and there is one journalist Abdul Aziz Shaheen who was abducted by Taliban and later on killed in military shelling when the Army targeted a Taliban hideout where he was kept.

During my stay in Pakistan a suicide bomber attacked a restaurant frequented by journalists close to the military cantonment in Peshawar killing 34 people including two journalists—Asfandyar Khan and Shafiullah Khan. Local journalists say that on several occasions militants from the nearby Bara area of Khyber Agency visited the place and threatened journalists for not reporting in their favor.

The attacks continue.

This June journalist Saleem Shehzad was abducted, tortured and allegedly killed by Pakistan Inter Services Intelligence (ISI). Journalist groups held protest demonstrations across the country expressing their shock and anger over his killing.

The government has constituted a commission to probe the murder but history shows scant cause for confidence that those guilty will be punished. Such commissions seldom even release their reports—and when they do, no action is taken to bring the people responsible to justice.

(Shaheen Buneri reported from Pakistan as a Pulitzer Center Miel Fellow.)