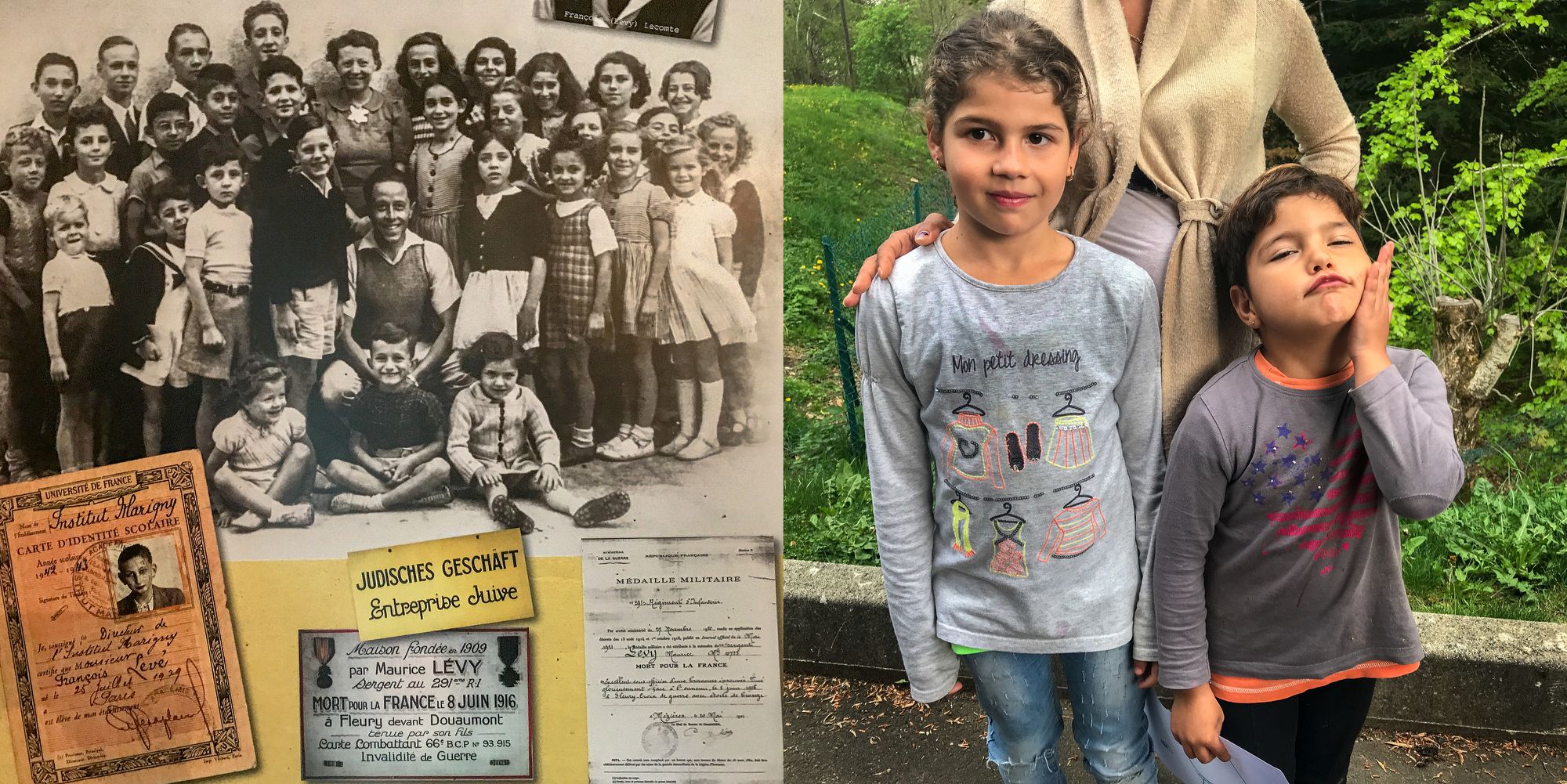

During World War II, the small village of Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, which lies isolated within imposing forests intermixed with vast farmlands on top of a 3,000-foot plateau in Southern France, did something extraordinary. Ordinary farmers and shopkeepers on the plateau became involved with what was later called a “conspiracy of goodness:” as they risked their lives to rescue nearly 3,500 Jews from the Holocaust in the “largest communal effort of its kind.” A villager interviewed said: “We didn’t protect the Jews because we were a moral or heroic people. We helped them because it was the human thing to do.”

Today, as the world turns its back on refugees from such war-torn places as Syria, Iraq, Chechnya, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, this village is welcoming them.

Read more about this story and see more photos in the July/August issue of Smithsonian Magazine.