Research-intensive assignments need a thematic frame, shaping a narrative line for readers to readily grasp. My work for GlobalPost and the National Catholic Reporter on the standoff between the Leadership Conference of Women Religion (LCWR) and the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (C.D.F.) came down to the headline: “A New Inquisition.”

Finding it was not a knee-jerk response nor an easy peg.

Before he became Pope Benedict, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger had been prefect of the C.D.F. under John Paul II. For nearly 25 years Ratzinger oversaw disciplinary proceedings against theologians and religious figures on birth control, Liberation Theology and other issues. The core dispute was obedience to the pope, through the C.D.F., or the magisterium, as the teaching office is known in Latin.

To many people the very idea is archaic: that sacred truth is defined by a single pope, through an office of doctrinal policemen, for a billion believers, most of whom have no interest in intellectual battles. But papal control of sacred truth is central to the orthodox consensus. Many orthodox Catholics take comfort in the idea of overarching truth. To them, too many nuns had left the ranch, gone liberal, become too feminist.

Before my trip to Rome, in two days of interviews with Sister Pat Farrell, the LCWR president, in Dubuque, Iowa, I saw the pressures of secrecy the system imposes. She and her colleagues would not speak against the process; they wanted to negotiate a solution.

To me, the story turned on the nature of that system.

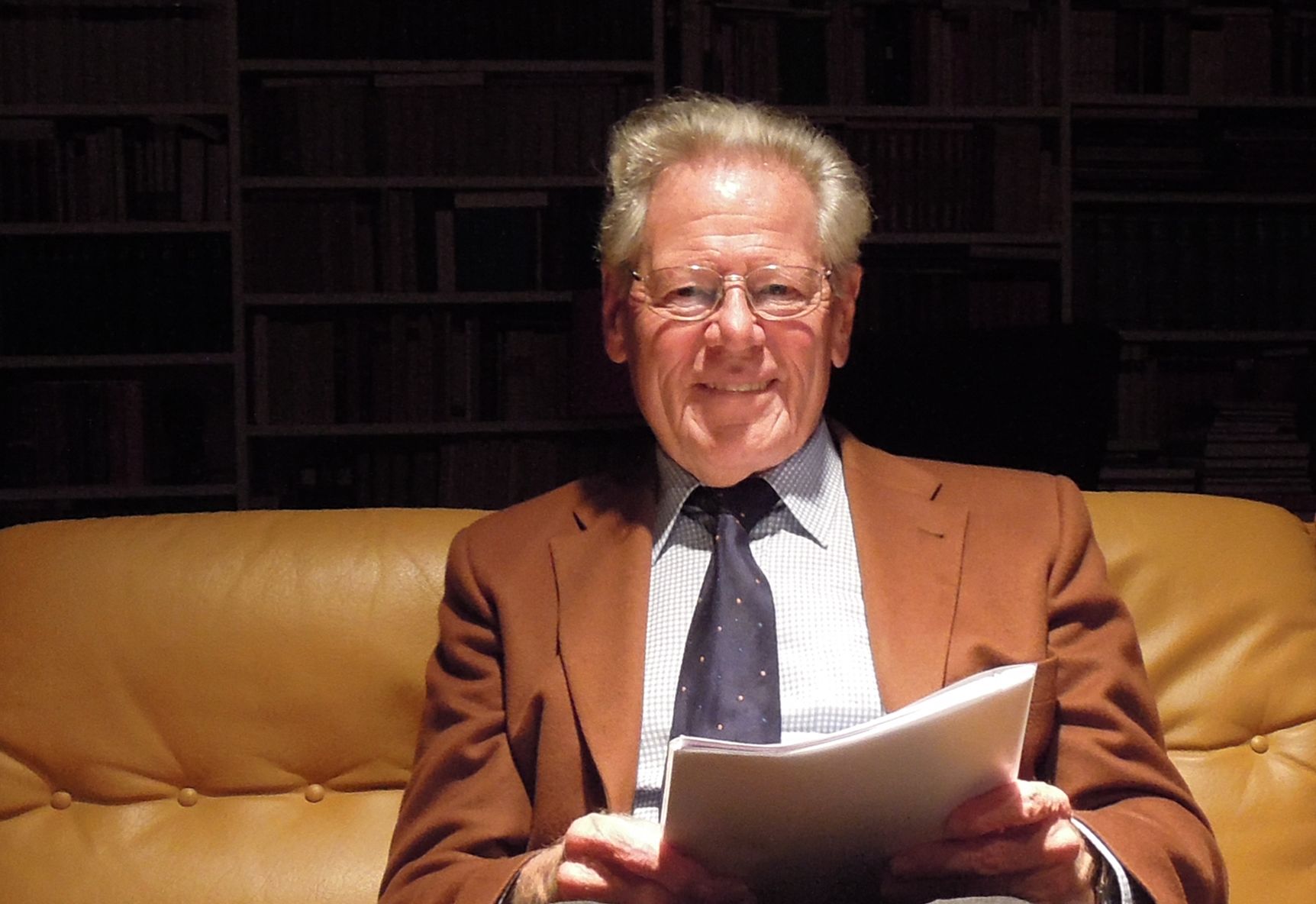

I cast lines for an interview with Professor Hans Küng at University of Tübingen, long a high-profile critic of the Vatican, curious about his view of the investigation. A prolific theologian and liberal thinker, Küng and the young Ratzinger had been faculty colleagues and theological advisers at the Second Vatican Council [1962-65]. As they split on divergent theological paths, Küng lost his teaching license under Ratzinger’s rule at the C.D.F. for challenging papal infallibility.

In preparation I re-read Paul Collins’s "{From Inquisition to Freedom" (2001) on seven cases of people who faced C.D.F. punitive charges under Ratzinger, including Küng and Collins himself. “Fundamentally,” writes Collins, “the C.D.F. lives in a time warp: despite attempts to tart it up in modern dress, it is essentially a creature of the sixteenth century whose methods have survived to the present day.”

I interviewed Collins in New York in 2002, after he clashed with the C.D.F. over his short paperback, “Papal Power” (1997), a historical analysis of how papal supremacy, without an internal give-and-take over the nature of justice, set the stage for the sex abuse crisis then beginning to surface. (The book had no U.S. edition; I paid $35 on Amazon and it was worth every penny.) Collins was not a theologian; but because he was in a religious order, Ratzinger wanted him to retract sections of a work of analytical history. Collins took all the “secret” correspondence, posted it on the web and after 33 years a priest, quit religious life.

Küng had been criticizing the process since the 1980s.

The story of the two priests, Ratzinger and Küng is an almost cinematic narrative. The charismatic Küng ends up losing his license to teach theology for challenging papal power, under Ratzinger, the shy, bookish cardinal, his one-time-friend. Now, as Küng the outlier nears retirement at 84, with an international reputation as an ethicist, Benedict, 85, has a papacy swamped in the abuse scandal. His own butler is in jail for leaking papal documents to a journalist.

When Küng set the interview date in emails, he asked if I’d like to read his forthcoming book, “Can the Catholic Church Be Saved?” The English translation was not yet done; I jumped at his offer of the French edition. Much of the book dwells on the revived methods of the Roman Inquisition which made heretics of church intellectuals at odds with the papal bureaucracy—Galileo, most famously, convicted in 1633 for (accurate) claims on astronomy. Küng treats Dostoevsky’s take on a soulless church in criticizing the Roman Curia for intellectual deceit. Küng uses metaphors of “sickness” and “exhaustion” and “moral cancer” in tracing the history of church scandals caused by denial of reality.

As in previous works, he compares Ratzinger to the Grand Inquisitor in “The Brothers Karamazov,” the cardinal persecuting heretics even as he himself has lost his faith.

In an October 5, 2012, profile by Kate Connolly in The Guardian, Küng upped the rhetorical ante: “The unconditional obedience demanded of bishops who swear their allegiance to the pope when they make their holy oath is almost as extreme as that of the German generals who were forced to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler.”

Benedict “has developed a peculiar pomposity that doesn’t fit the man I and others knew,” he told Connolly. “Now he’s frequently to be seen wrapped in golden splendour and swank...and has even had the garments of the Medici pope Leo X remade for him.”

When I arrived at his two-story home office, Küng courteously invited me to have coffee. But before we sat down he began questioning me about my reporting on the Vatican mishandling of the notorious pedophile, Father Marcial Maciel. It was an odd sensation, being grilled by a scholar famously critical of Vatican interrogations about articles, a book and documentary I had done. But Professor Küng is not a man lacking in charm. He wore a hearing aid, had a penetrating gaze and listened very carefully. “So,” he said finally, “let us take our seats,” and showed me to a couch next a table at the level of the knees, with napkins, small spoons, and cookies. He made an odd request as we began: I could quote him however I wished in the reporting, but not run a q-and-a transcript. I offered to let him read the taped transcript. “That is what I wish to avoid,” he sighed. “It would be a boring affair.”

The easy part was drawing out his view of the nuns’ investigation as a new Inquistion. He surrounded the idea, offering examples of the Curia’s persecutorial mindset. In due course I challenged him on the remark to Connolly in The Guardian, likening the bishops to Nazi generals with loyalty oaths – was it not too explosive, too extreme?

“I think the metaphor is appropriate,” he said in his ever courtly way. “No one has the courage to speak out. The oath of the bishops [to papal loyalty] is in a certain sense even more serious than the oath to the Fuhrer.” Because obedience imposed limits, he continued, it meant “you can cover everything.”

“Is this justice?” he resumed, warming to his topic.

“That’s absurd. The question of truth comes first.”

And then, for my purposes, he gave the line that speaks volumes about the crisis of the church today: “Is it one boss who has the truth, and not much justice?”