In the Americas, the arrival of Europeans brought disease, war, and slavery to many indigenous peoples. Can some of the world’s last isolated groups avoid those fates as they make contact in the 21st century?

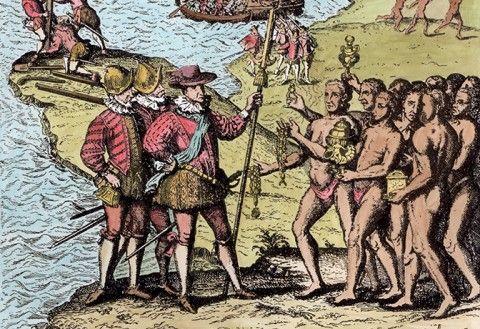

When the Taino gathered on the shores of San Salvador Island to welcome a small party of foreign sailors on 12 October 1492, they had little idea what lay in store. They laid down their weapons willingly and brought the foreign sailors—Christopher Columbus and his crewmen—tokens of friendship: parrots, bits of cotton thread, and other presents. Columbus later wrote that the Taino “remained so much our friends that it was a marvel.”

A year later, Columbus built his first town on the nearby island of Hispaniola, where the Taino numbered at least 60,000 and possibly as many as 8 million, according to some estimates. But by 1548, the Taino population there had plummeted to less than 500. Lacking immunity to Old World pathogens carried by the Spanish, Hispaniola’s indigenous inhabitants fell victim to terrible plagues of smallpox, influenza, and other viruses.

Epidemics soon became a common consequence of contact. In April 1520, Spanish forces landed in what is now Veracruz, Mexico, unwittingly bringing along an African slave infected with smallpox. Two months later, Spanish troops entered the capital of the Aztec Empire, Tenochtitlán (shown above), and by mid-October the virus was sweeping through the city (depicted above in images from the Florentine codex, a document written by a 16th century Spanish friar), killing nearly half of the population, which scholars today estimate at 50,000 to 300,000 people. The dead included the Aztec ruler, Cuitláhuac, and many of his senior advisers. By the time Hernán Cortés and his troops began their final assault on Tenochtitlán, bodies lay scattered over the city, allowing the small Spanish force to overwhelm the shocked defenders.

But not all indigenous groups suffered such a grim fate. The smallpox virus spread more easily in densely populated Tenochtitláan than it did in sparsely inhabited regions, such as the Great Plains of the United States. There migratory hunter-gatherers followed the great bison herds, and disease outbreaks were sometimes contained in single bands. During the smallpox epidemic of 1837 to 1838 along the Upper Missouri River, for example, some Blackfoot bands suffered heavy losses, while neighboring Gros Ventre people escaped nearly unscathed. The Gros Ventre were ultimately forced to live on reservations, where some left beautiful “ledger art” (see above), drawing and preserving details of their dress and way of life in ledgers provided by Bureau of Indian Affairs agents. Contact with Europeans also brought one major benefit to Plains populations: the horse, which made following and hunting bison herds easier.

In remote parts of the Americas such as the Amazon, resource extraction has driven many contacts with indigenous groups. During the late 1880s, European and American industries producing gaskets, electrical insulators, bicycle tires, and other goods created an immense demand for rubber. Amazon forests were rich in rubber-producing trees: All that was lacking, it seemed, was a local workforce to tap them. Unscrupulous rubber merchants eventually enslaved “hundreds of thousands of Indians” from isolated Amazonian tribes to work as rubber tappers, according to a 1988 study by the International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. To evade capture, many isolated tribes fled into ever more remote regions of the rainforest, where a few remain isolated even today. In 1914, new rubber plantations in Asia and Africa supplanted Amazonian rubber.

At the turn of the 20th century, projects such as the construction of telegraph lines and highways began pushing into the Brazilian Amazon, often cutting through territories inhabited by isolated tribes. To lure nomadic hunter-gatherers out of the forests and into settled communities, government representatives used a technique known as the “attraction front” for many decades. Leaving out gifts of metal tools in gardens or tied to ropes in a forest clearing, they wooed isolated groups into contact, and later forced them to work for consumer goods they had come to depend on. But contact on these fronts often led to the transmission of diseases, until the Brazil government adopted an official “no contact” policy in 1988 and phased out these practices.

During the late 1950s and 1960s, a group of Yanomami living near the Venezuelan border were nearly wiped out by measles and another contagious disease after they made contact with the outside world. Nearly 40 years later, a surviving child, Davi Kopenawa, described how contact happened. Along the Araçá River, Kopenawa’s grandparents and others met white people for the first time and spotted their metal tools. “They longed for them,” Kopenawa recalled, and occasionally visited these strangers to get a machete or ax. They then shared the tools freely among their community. Today, after contact, the Yanomami number around 32,000, and Kopenawa is an important advocate for his people.

2011 aerial footage of an uncontacted tribe near the border of Brazil and Peru.

In 2007, the president of Peru, Alan García, declared publicly that there were no isolated groups remaining in Peru’s Amazon forests. Environmentalists, he claimed, had invented “the figure of the uncontacted native jungle dweller” in order to stop oil and gas development in the Amazon. Many anthropologists strongly disputed this. In Brazil, the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) has confirmed the existence of 26 isolated groups and has found indications that as many as 78 additional groups may be in hiding or on the run. To monitor Brazil’s isolated tribes and protect their territories, FUNAI employees conduct periodic flyovers of remote forest villages. This video above was taken during a 2011 flyover in the Envira River region along the border of Brazil and Peru.

Today contacts—sometimes initiated by isolated groups themselves—appear to be on the rise in both Brazil and Peru, perhaps as tribespeople flee illegal logging or drug trafficking. In August 2013, forest rangers in the Peruvian Amazon videotaped the appearance of 100 members of an isolated group known as the Mashco Piro near the community of Monte Salvado. The tribespeople, armed with weapons, seemed to threaten the onlookers. Just over a year later, 100 Mashco Piro men descended on Monte Salvado while most of the inhabitants were away voting. The tribesmen broke windows, killed the villagers’ dogs and chickens, and chased away four community members. Some in the area now think the attack was motivated by hunger. One species of Amazon peccary has become rare in the region, and turtle eggs, a dry-season staple, were in short supply in 2014 due to earlier flooding.

In 2014, FUNAI officials made contact with three isolated groups in Brazil. In late June, one of these groups, now called the Xinane, emerged from the forest near the village of Simpatia. The young tribesmen eventually entered the village, pilfering some clothes and metal tools, but they were mainly peaceful. It was their first official contact with the outside world. A day later, FUNAI team members noticed that the Xinane were coughing and looked sick. When a doctor finally flew in 6 days later, he treated them for what turned out to be a relatively mild virus, and the tribesmen recovered. FUNAI officials say that to avoid repeating the tragic history of epidemics, they need the resources for competent and skilled interventions.