There’s a four-bedroom house for sale in Moorhead, Minnesota. “Perfect location,” the listing says. There’s a golf course next door and a shopping center across the street complete with bank, salon, hotel, and fast food. For this 160 acres, the United States paid the eastern bands of the Dakota, the Indigenous people of the region, approximately $3.78 cents for title. The land was later granted to the state of Mississippi to fund Alcorn State University and Mississippi State University. In total, the two land-grant universities raised $143.50 from those 160 acres, a return of 38-to-1 for every dollar spent to acquire the land from the Dakota.

This is how the land-grant university system began in the US. The Morrill Act of 1862 granted expropriated Indigenous land to states in order to fund universities. Indigenous territory acquired through lopsided treaties and outright seizures was funneled through the act to make advanced agricultural and mechanical education more widely accessible.

The lands were usually sold quickly to raise money for college endowments, but in some cases, they remain in the possession of the states and continue to produce revenue for their associated universities. In all, the act redistributed 10.7 million acres of land from more than 250 tribal nations for the benefit of 52 colleges — an area approximately the size of Denmark.

Nearly 160 years after the signing of the Morrill Act, a team consisting of a historian, cartographer, photographer, fact-checkers, web designer, coder, and reporters, investigated the impact of this landmark legislation on tribal nations and universities. In partnership with the Fund for Investigative Journalism and the Pulitzer Center, the Land-Grab Universities investigation was published by High Country News, a nonprofit news organization covering the western US.

From the first explorers to colonial settlers, newcomers to what is currently the United States have killed or removed Indigenous people from the continent, resulting in the deaths of tens of millions — actions that meet international definitions of genocide. With the elimination of Indigenous communities, land was opened for settlers. The US and its citizens have been loath to refer to those actions as genocide, but our investigation provides a window into the process by revealing one set of institutions that directly benefited from the act: land-grant universities.

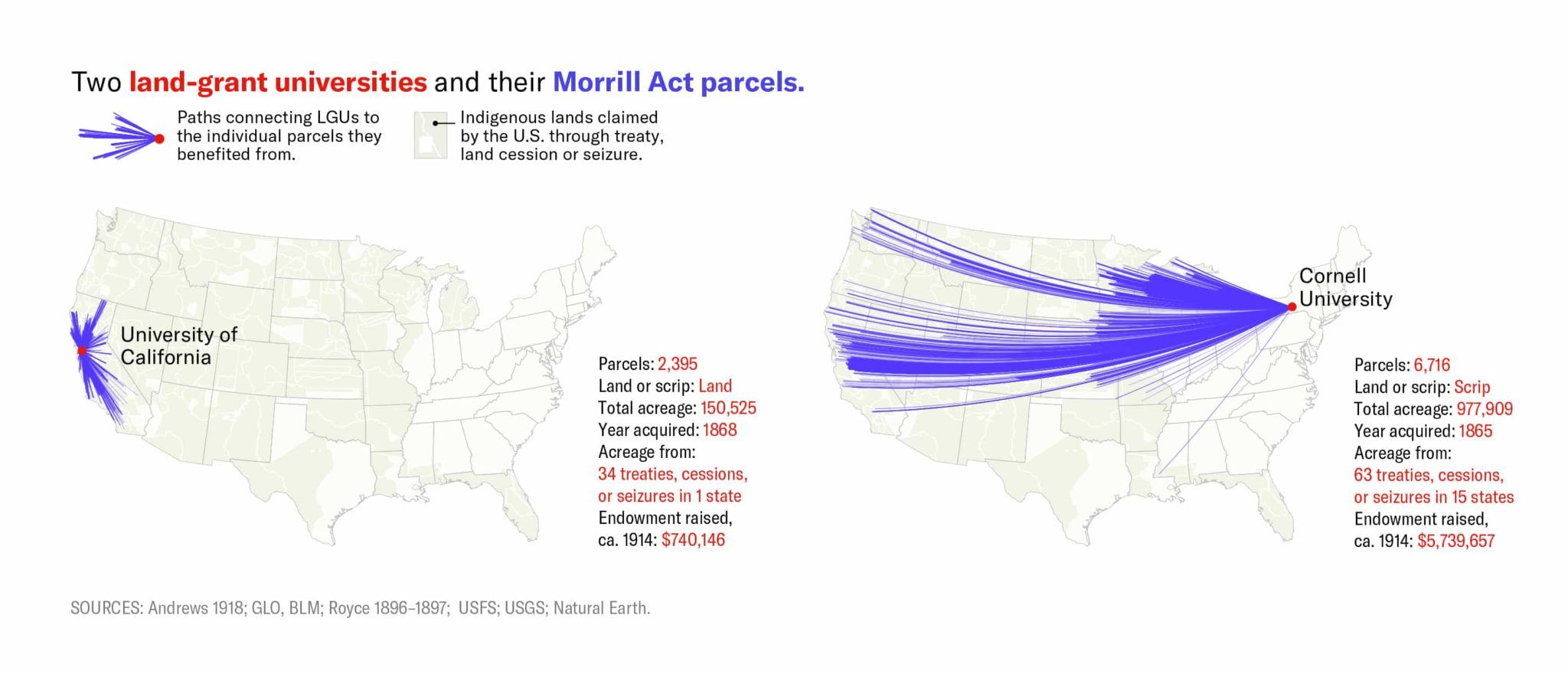

Nowadays land-grant universities enroll more than a million students and perform cutting-edge research, but they offer little acknowledgment that the foundation for their success lies in the dispossession of Indigenous land and eradication of Indigenous people. From Cornell University to the University of California, land-grant universities are some of the most prestigious colleges in the US. Only now are we beginning to see the links between higher education and colonialism through data.

Investigating Untold Histories

At the core of our investigation was the development of a custom geodatabase that reconstructs the Morrill Act’s enormous, scattered footprint. Our data maps approximately 80,000 individual land parcels, spread out over 24 states. For each parcel, we identified the Indigenous cessions through which the US claimed the land and contrasted the price paid for Indigenous title, if anything, to money raised for university endowments — money that remains on the books today.

With this data on hand, we could overlay the land grants on existing maps of Indigenous land cessions and identify, for the first time, the connections between university beneficiaries and the land’s original owners and caretakers. To gain a sense of how the Morrill Act redistributed wealth, we researched payments made to tribal nations for the land that supplied the grants, as well as money raised for universities from land sales, and distributed them across the dataset.

Drawing on the data surveys, we told the story of the intertwined histories of the dispossession of tribal nations and the growth of fledgling land-grant universities. We dispatched photographer Kalen Goodluck to the actual land parcels to document how the land was being used today. His travels took him from Minnesota down through Nebraska, as well as Nevada, California, and Washington state.

Using the geodata to guide his photography, we were able to put a “face” to the story through old-fashioned shoe-leather reporting: it was through Goodluck’s time on the land that we were able to establish that the Directors Guild of America in Los Angeles, California, was built on a parcel of land taken from nearly a dozen tribal nations and granted to the University of California. Marrying that location with payment information we collected, we could show that the US paid nothing for that land, despite signing a legal agreement with those tribes, while the University collected $786.74 from its sale.

An accompanying website enables readers to sift through the database themselves and find places like the 160-acre tract in Moorhead, Minnesota. By making all our data available to explore through interactive maps and tables, or for download, the project invites newsrooms, researchers, tribal governments, and universities to reconsider the foundations — and responsibilities — of the land-grant system.

Building the Geodatabase

There is neither a single source of Morrill Act land parcels nor a comprehensive accounting of how many acres were distributed through the Morrill Act. To compile a directory as complete as possible, we created a master list of Morrill Act parcels state by state. We identified the land parcels from a range of digital and archival repositories and extracted most of our data digitally, pulling tens of thousands of land patents that were tagged as issued under the legal authority of the Morrill Act, from the US Bureau of Land Management’s General Land Office database.

To fill the significant gaps that remained, we went to the National Archives in Washington, DC, where we photographed Morrill Act parcel selection lists compiled by states. Brittle and often tied up in twine, many of these documents appeared to have been untouched since being archived.

We completed our search by consulting printed lists of agricultural college land offered for sale. Some were available digitally, while others were located at special collections at colleges — like the University of Missouri, Columbia — as well as state selection lists available on microfilm and microfiche. While we were usually able to pull data on acres, locations, and beneficiaries from the BLM database, corresponding information from archival and print sources had to be transcribed by hand. In many cases, illegible or missing records created undercounts.

Our search yielded a database of 79,461 Morrill Act land parcels that had to be mapped. Using their public land survey descriptions, we created polygons for all the parcels using online maping tool ArcGIS. We were able to draw precise polygons for roughly 97% of the parcels, and locate nearly all the rest to within one square mile or less. A negligible portion — less than one-tenth of 1% — could not be mapped due to incomplete or illegible location descriptions.

With these locations identified, we could now use spatial analysis to specify Indigenous sources of the grants. To establish Indigenous land cessions we relied on maps created for the Smithsonian, a museum and research institution managed by the US federal government, in the late 19th century by cartographer Charles Royce, a standard used by courts and historians throughout the 20th century and now publicly available as shapefiles. We spatially joined these shapefiles to our Morrill Act parcels to establish “original ownership.”

It’s important to note that while the Royce maps represent who the US entered into legal agreements with, they are not entirely accurate, particularly from Indigenous perspectives: The maps often leave out tribal nations living in the same areas who may have resisted US expansion and been forcibly removed, exterminated, or excluded from negotiating treaties with the federal government. Those legal agreements made by the US have still not been honored or enforced to this day.

Tracing the Money

After connecting university beneficiaries to Indigenous land sources, we conducted research on treaty payment histories, endowment principal raised from the Morrill Act grants, and the value of unsold grant land in an effort to shed light on the Morrill Act’s function as an Indigenous wealth transfer. This required consulting copious legal documents, federal accounting reports, and compilations of land-grant college statistics.

Our research revealed that by the early 20th century, the grants were worth about $22.8 million in endowment principal and unsold land, or about half-a-billion dollars when adjusted to current values. By contrast, we found that the US paid just $400,000 dollars for Indigenous title to the same land, although much of it was simply seized. Not a single dollar was paid for more than a quarter of the parcels that supplied the grants.

The funds raised through the Morrill Act are still on the books generating income for their beneficiaries. And as we discovered during the reporting process, over a half million acres of Indigenous land redistributed through this law are still owned by states for their respective universities.

Holdings of so-called “mineral acres” — land that contains oil, natural gas, or other extractable minerals — are even more extensive. Unlike the parcel sold in Moorhead, Minnesota, these retained surface and mineral acres continue to generate sizable incomes — at least $8.6 million in fiscal year 2019 alone — for their associated universities and leave lots of opportunities for reporters to ask questions of institutions and report on the ongoing impact of the 1862 law.

The investigation was published as the full force of the COVID-19 pandemic hit the US, and so far, university response has been muted. However, the project continues to receive recognition and spark conversation. At multiple universities, we have learned that students and professors have begun using the data to advocate for tuition reform for Indigenous students, to fund Indigenous faculty positions, create accurate curriculum for land grant students to learn the factual history of their institutions, and even discuss the possibility of establishing land buy-back programs to restore traditional homelands for tribal nations. As well, with COVID-19 coverage leveling off, many newsrooms are beginning to dig into the data in order to localize stories and focus on their local universities and associated tribal nations, while follow-up stories continue to be reported.