In South Florida’s Haitian-American community, a simple, self-testing kit for cervical cancer is increasing the percentage of women being screened for the disease — and overcoming cultural and access barriers that traditionally have made the population hard to reach.

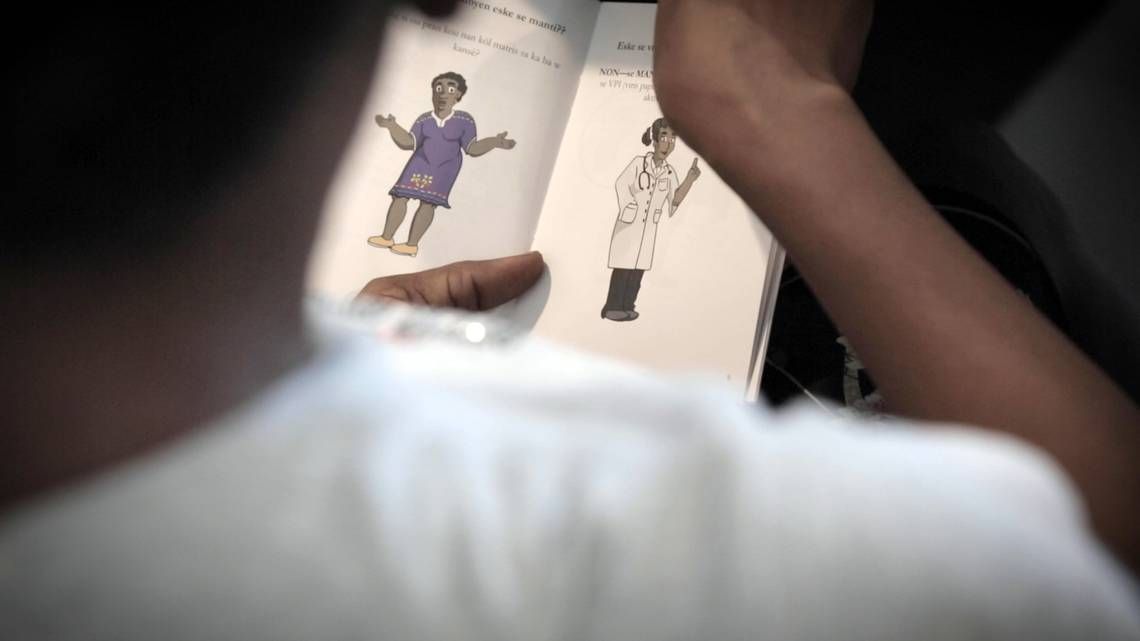

The kit is basically an oversized Q-tip with diagrams showing how to use it before the sample is sent for testing. It is also used 700 miles away in Haiti, a country where deaths from the preventable disease are a growing national problem — and the obstacles to screenings are also similar.

“It’s cultural, it’s financial, and it’s women not being too comfortable with [the Pap smear] exam,” said Gepsie Metellus, a Haitian community activist who has long been concerned about the “alarmingly high cervical cancer rate” among Haitian women. “For many women, the idea of having to see a male doctor is already very concerning, and if not provided a choice to see a female physician, they will double-down and not go.”

The kit addresses both cultural and access issues, and it’s being offered in a mobile clinic from the University of Miami’s Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center. The clinic is known as the “Game Changer” and travels to four medically underserved communities, including Miami’s Little Haiti.

“Anybody who interacts with the Game Changer in Little Haiti, or Hialeah, or South Dade... gets access to a screening technology that’s low-cost, easy to use, and was actually inspired by the work that was started in Little Haiti 14 years ago,” said Erin Kobetz, associate director for population science and cancer disparity at Sylvester.

Back in 2006, Kobetz, a Miami native and medical researcher, tested the theory that self-sampling might be more acceptable to Haitian women than Pap smears, which have long been considered the gold standard for cervical cancer screening in the developed world but had been resisted by many Haitians.

She did a field test in Little Haiti and then in Haiti’s Central Plateau, where she worked with Zanmi Lasante, the sister organization to Boston-based Partners In Health, to see if women in Haiti would also use the kit. They did, and Kobetz took the lessons learned in Haiti back to Miami, she said.

As a newly recruited UM researcher, Kobetz had wondered why an area of Northeast Miami-Dade County had an unusually high rate of cervical cancer. That pocket of Miami turned out to be Little Haiti, where 38 women out of every 100,000 had the disease. The rate was more than four times that of women in other parts of Florida and the United States. In Haiti, cancer rates are difficult to track and vary widely. But the World Health Organization says cervical cancer is the second most common cancer in women there and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in women, after breast cancer.

Kobetz reached out to Metellus and other Haitian community leaders for help in understanding what was going on. It turned out that while most publicly available data suggested that black women got screened for the cancer through Pap smears in equal numbers to their white counterparts, that was not the case among Haitian women. They didn’t like the test and held several negative perceptions about it, including fears that their partners would not approve of it.

“We’re getting lumped into this broader category of black and it’s distracting from an understanding on what our needs are, the challenges we have in accessing prevention,” Kobetz recalled female community leaders telling her.

Kobetz knew she had to come up with a strategy for prevention that fit into Haitian women’s cultural framework. The new approach should not require physician involvement or a pelvic exam that compromised notions of modesty but work as well as a Pap test.

One of her medical school students, she said, suggested using a self-sampler that until then had only been used in a clinical setting.

Kobetz decided to pair Creole-speaking community health workers with the kit to see if female Haitian immigrants, many of them recent arrivals, would agree to collect their own vaginal cells in the privacy of their homes.

“Any time a community health worker would show up at the home of a woman whom she had previously set an appointment with, that woman had her aunt, her cousin, her sister ... there. Everyone wanted to do it,” Kobetz said.

Women were taught how to use the swab, similar to a tampon, and then dip it into a solution that is shipped to a lab. The specimen is tested for the human papillomavirus (HPV), the principal cause of cervical cancer.

If the test came back positive, they would need further care. Self-collecting, which has since been studied in Haiti by others, eliminated barriers of a pelvic exam.

“It puts the power of screening in the hands of the woman,” Kobetz said. “[And] it doesn’t require access to the formal healthcare system in order to participate in a cervical cancer screening.”

Haitian-American leaders said the self-sampler has allowed more women to get screened, and Kobetz’s research in the past 12 years has raised awareness of cervical cancer in the community. She is now investigating the reasons behind Little Haiti’s increased cervical cancer rates.

“Initially, the women were skeptical because they really didn’t believe it was possible,” said Marleine Bastien, a Haitian community activist whose Family Action Network Movement organization has been a longtime collaborator with Kobetz. “As the research progressed, they understood they had the power in their hands as women to make sure they are healthy.”

Still, getting Haitian women to be proactive in preventing a disease that doesn’t need to reach an untreatable stage remains a challenge, Bastien said. “There’s still outreach to do.”

Kobetz said over the past 12 years, the number of Haitian women getting regular screenings has increased from 44 percent to 60-70 percent. She believes her research in the Haitian diaspora has influenced screening initiatives in Haiti, where she’s working with Haiti sans Cervical Cancer, a consortium of U.S.-based providers, to create a cervical cancer registry. Some of her educational materials are also being used by the health nonprofit, Innovating Health International, in its HPV screening program in Haitian factories, where many women work.

“We can say that more women are aware of cervical cancer and the importance of earlier detection of disease,” Kobetz said of Miami’s Haitian community. “We alone have screened thousands of women who otherwise would not have benefited from early detection of disease and built important bridges for many of them to access cancer prevention.”