Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – When she gave birth on Dec. 16, 2015, Fabiane Lopes named the youngest of her three daughters Valentina Vitoria.

“Valentina because she is brave,” Lopes explains, “and Vitoria for victory.”

The description could apply to the mother, too, for she chose to keep the baby — born with birth defects related to the Zika virus — against her husband’s wishes.

Lopes lives with Valentina, a son and two other daughters in a tiny apartment behind a furniture plant in Duque de Caxias, a suburb of Rio de Janeiro. Between the second and third months of pregnancy, she fell ill with the Zika virus, which is mainly spread by mosquitoes. For a week, she suffered fever, headaches and pain. She felt very weak.

But the hardest blow was still to come. At the ultrasound, four to five months into her pregnancy, the doctor said the baby had microcephaly, a birth defect linked to Zika and marked by an abnormally small head and underdeveloped brain.

News of the baby’s condition upset her husband, whose name Fabiane declines to give. Shortly before Valentina’s birth, the two parents exchanged text messages:

“Maybe it would be necessary to take the baby before it’s time,” Lopes texted.

“To abort,” he replied.

“No, to make a treatment outside in another place.”

“Fabiane,” the husband texted back, “you know what I think about this child. So what do you want from me?”

“Then the thing you want the most,” Lopes wrote, “is that she dies.”

“Yes,” he replied.

He left before Valentina’s birth and has not returned.

***

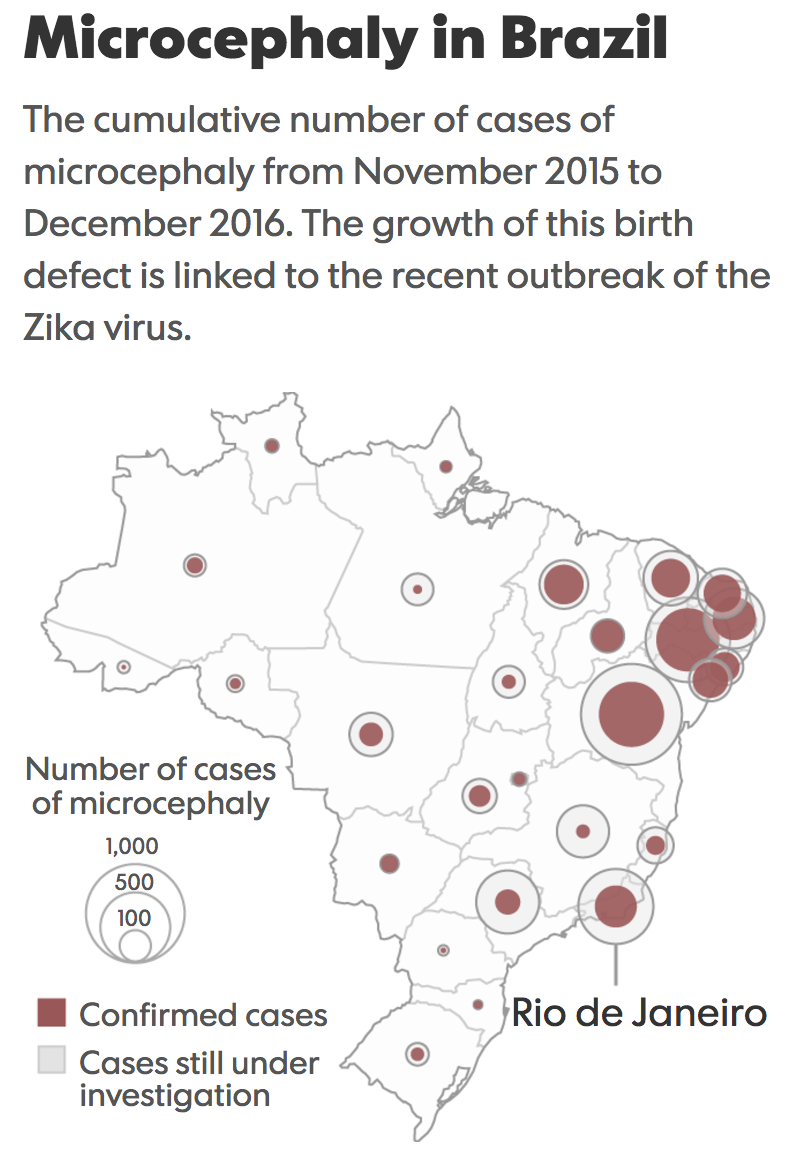

Valentina is one of 2,366 babies with microcephaly born in Brazil between November 2015 and December 2016.

While Zika remains a problem in Brazil, it has slowed significantly. According to Ana Bispo, a virologist at the Oswaldo Cruz Foundation in Rio de Janeiro, there were 4,900 reported Zika cases in Brazil during the first 12 weeks of 2017, a huge drop from the same period in 2016, when the nation saw more than 142,000 Zika cases.

While Zika remains a problem, Brazil recently declared it no longer a public health emergency, following a significant mosquito eradication program.

In the United States, there have been more than 5,200 Zika cases reported since Jan. 1, 2015, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. There have been 58 infants born since 2016 with birth defects possibly caused by Zika.

The Zika virus interrupts formation of the brain during a critical stage of fetal development.

“The virus crosses the placenta and infects the neurons,” Bispo says. “It blocks the development of the brain. The brain itself, it does not grow.”

Once a pregnant mother learns her baby has microcephaly, there is nothing she can do.

“There is no medication for Zika,” Bispo says. “There is nothing.”

***

When she saw the ultrasound of her baby, Lopes did not understand what microcephaly was. The doctor told her that the head was smaller. She could see the feet were not right either; the baby had the deformity known as clubfoot.

The doctor was not even sure the baby would survive.

It wasn’t until a week before the birth that Lopes gained a fuller understanding of her baby’s condition. She was on Facebook and saw a picture of a baby with microcephaly.

The condition is linked to seizures, hearing loss, vision problems, intellectual disability and problems with balance and movement. Scientists say more studies will need to be done to determine the long-term effects of Zika-related microcephaly.

Lopes gave birth to Valentina at 37 weeks, a little earlier than the normal 40. And for at least a moment, it didn’t matter that the baby looked different.

“I felt so happy,” Lopes says, speaking through an interpreter. “I felt love when I had the baby in my arms.”

Soon after, the doctor asked if she wanted a tubal ligation to ensure that she would not have any more children. Lopes said yes.

Without a husband to help her, she knew motherhood would be difficult. She asked God for wisdom.

Today, 16 months after her baby’s birth, she has a better appreciation of what it means to raise a child with microcephaly.

Valentina is in almost constant pain, which means Lopes goes nights without sleep. “It’s not easy, but I will not give up,” she says.

The mother has faced difficult times before. Her daughter, Julia, now 4, was born with microcrania, a condition marked by a smaller-than-normal cranium.

“People said she would not walk. She would not talk,” Lopes says. “Now she talks. She sings. She dances.”

Julia’s progress gives her hope for the baby.

Valentina’s pain has meant a slew of medications, which drain the family’s finances every month.

Lopes receives 934 reais (about $300) in assistance from the federal government each month. But the costs of Valentina’s medicines alone add up quickly. Depakene, a medication used to treat seizure disorders, costs about $6 for each box, and she goes through four boxes each month. Another anti-seizure medicine, Vidmax topiramato, costs $25 to $28 for each box. There are other medications, too.

Paying is a struggle without her husband, who had a steady job at a beer factory. Her own mother is dead, and she has no other extended family. Lopes and her family must depend on support from neighbors and friends.

She takes Valentina to see the doctor as often as she can, but it is difficult to reach the hospital on time. Lopes misses appointments either because she can’t afford bus fare or the bus gets caught in rush hour traffic.

Valentina looks younger than 16 months. She is a little smaller than normal for her age. Because she cannot eat with her mouth, she requires a feeding tube.

Valentina was also born with a scar near her eye. Lopes says it is unclear how much she can see, if at all. “I have to wait for her timing and God’s timing, but I hope that her sight will normalize,” Lopes says. “Her sight is very fragile.”

When Lopes takes her baby daughter out in public, “people look a lot (at Valentina),” she says. “When someone starts looking too much, I start kissing her to show love.”

She imagines her daughter saying, “My mom loves me so much that she doesn’t even see that my head is smaller.”

When Valentina cries out, which is often, the other children come running to hold her and kiss her. The older girl, Eduarda, 9, helps a great deal, feeding Valentina, changing her and holding her.

“I taught them to love Valentina as I do,” Lopes says.

Valentina loves the stimulation provided by music and toys, and does exercises to help her feet. The physical therapy is important, says Fernanda Daniel Fialho, a doctor in Rio de Janeiro, specializing in pediatric intensive care.

Fialho says it is not clear yet whether the babies affected by Zika will ever learn to walk and talk. “We don’t know if they will grow up healthy. We don’t know the disease.”

In the absence of answers, Lopes provides the one thing she can: a mother’s devotion.

“Everything I do, I do for her,” the mother says, her brown eyes widening as she talks about Valentina.

“I do everything I can. If God does take Valentina, at least I will know I did all of my best for her. I did everything I could. I could do no more."

Zika

Virus first found in Uganda in 1947.

Transmission

Mosquito bite from two species, aedes aegypti and aedes albopictus. Zika can be passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus, leading in some cases to the birth defect microcephaly. The virus can also be transmitted sexually, and may be capable of spreading through blood transfusion.

Geographic Regions

The World Health Organization says 84 countries, territories and subnational areas have shown evidence of mosquito-borne Zika.

Symptoms

Most experience mild symptoms. These may include fever, rash, red eyes, headache, joint and muscle pain.

Severe Symptoms

Zika infection during pregnancy can lead to microcephaly and other brain defects. The virus has also been linked to the nervous system illness Guillain-Barré Syndrome.

Cases and Death

The World Health Organization has no solid numbers of worldwide Zika cases or deaths attributed to the virus.

In the U.S.

Through May 3, there have been 5,274 cases of Zika reported in the U.S., most from travelers, but about 224 acquired from local mosquitoes in Florida and Texas. About 1,793 pregnant women in the U.S. have shown lab evidence of the Zika virus.

Treatment

No antiviral drug. Doctors treat dehydration and kidney and liver failure.

Source: World Health Organization