The story begins innocently enough. Fertile soil attracts labor from far and wide. Factories provide employment, farmland is plentiful, and for a time the economy of Ivory Coast booms as a much-desired commodity – cocoa – is exported across the globe.

But the story of cocoa has never been an innocent one. So valuable in the Aztec court that it was used as currency, blood has been shed over cocoa profits since Europeans first developed a taste for chocolate. Over the past two centuries, farming and production have moved from country to country, from the Caribbean to West Africa, always dependent on rich farmland and cheap labor.

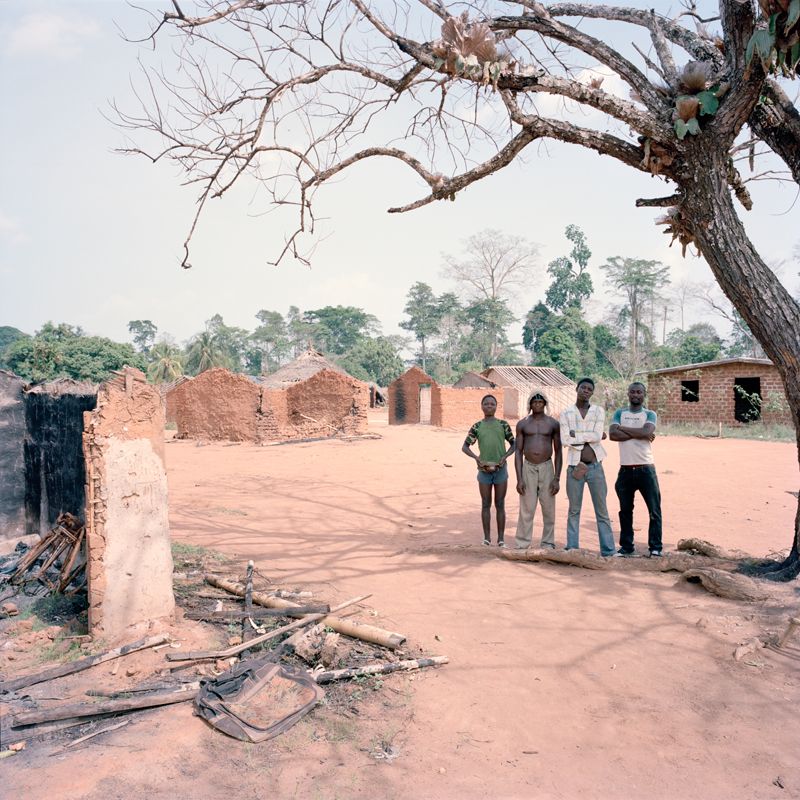

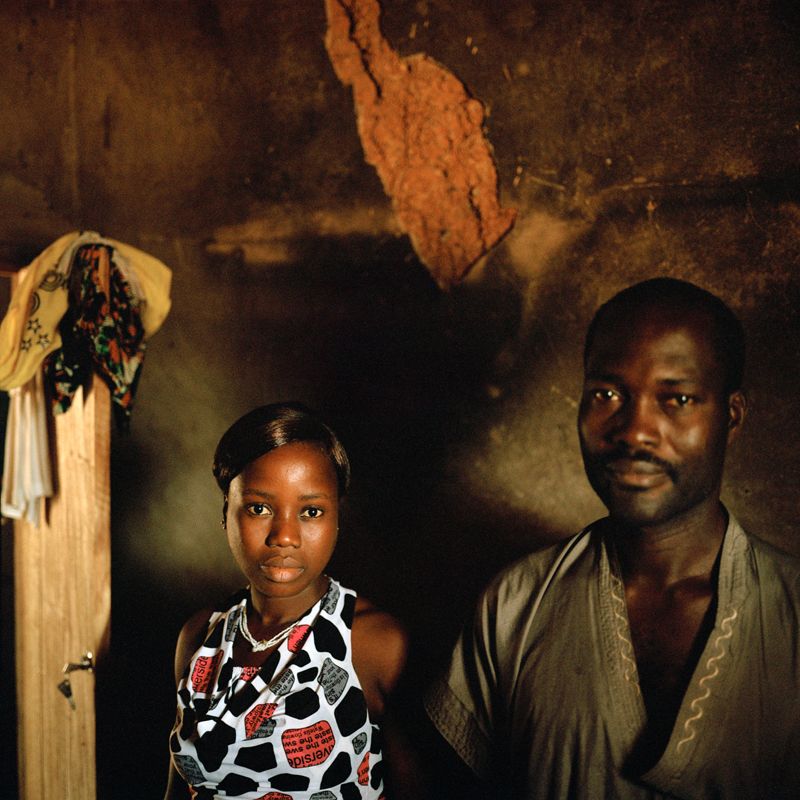

Ivory Coast’s ethnic strife is the most recent chapter in cocoa’s troubled history. Initially migrant workers from across West Africa were invited to the country to share in its farmland, helping Ivory Coast become the world's top producer. (Today it provides some 40 percent of the world's crop.) But once the economy went sour in the 1980s, cocoa profits were more jealously guarded. Land disputes erupted, sparking xenophobic violence that became a 10-year civil war.

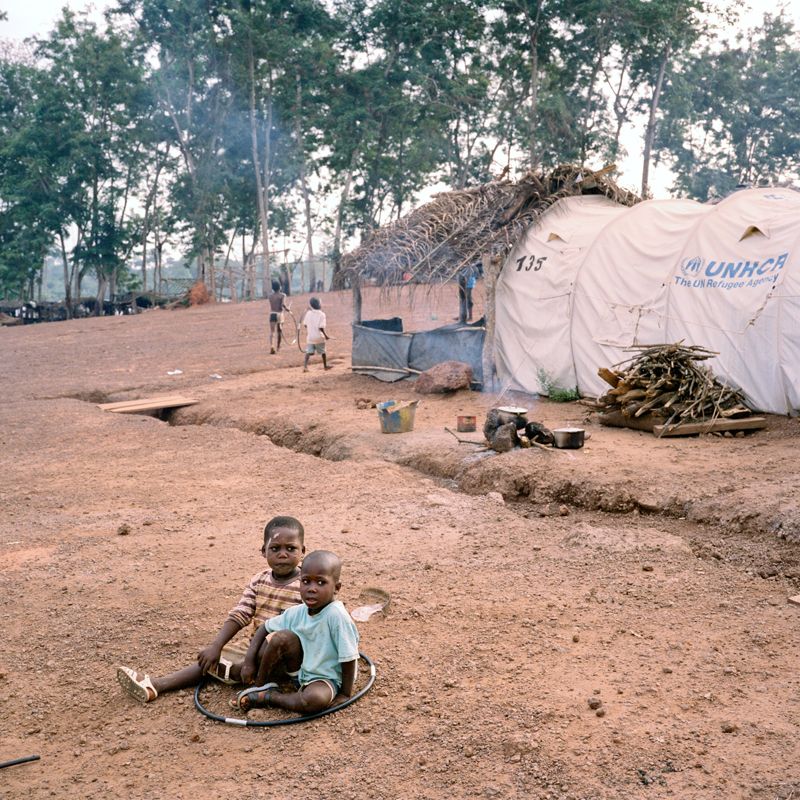

With the cessation of post-election violence last year and the ascendance of a new government, the war is supposedly over. But new attacks are still carried out between rival factions; thousands of people still live in refugee camps; and those who return to their destroyed homes swear vengeance. As always, cocoa production continues through the strife — but reconciliation and a true end to conflict may still be a long way off.