Samira is the oldest of her sisters. She lives in Najaf, the world's third holiest Islamic city. Samira's faith is in Allah's word, the Quran.

Najaf's streets were busy and beautiful. Men in gowns called dishdashis and women in black and blue abayas walked to and from fruit carts, stores, restaurants and taxis. All the women in Najaf wear abayas because Imam Ali ibn Abi Talib, Prophet Mohammad's cousin, is buried in the city. The women I'd seen in Baghdad and Erbil wore jeans, blouses, skirts, dresses, wedged heels or sandals.

Rasul stopped at a nearby restaurant to pick up Iraqi-style kabob and grilled whole tomatoes before our visit to the Imam Ali.

Unlike Baba, I'm not a very spiritual person. I stopped believing in Allah the summer leading to eighth grade. My grandfather in Iraq was very sick that summer and Baba had finally saved enough money to reunite with his family.

Overhearing my grandfather's health issues at dinner, I decided to pray for him before bed.

I remember getting out of bed, opening the curtains and peering out at the moon. I started praying like Baba had taught me. At the end of my prayer, I read a dua, prayer of request, asking for my grandfather's recovery. The next morning, Baba got a call from Iraq saying that his father died in his sleep.

"I want to visit jido (grandpa)," I told Samira and Rasul while we ate kabab.

Rasul, with a kabab wrapped with pita in one hand, stopped and looked at Samira.

"How did you know he was buried here?" Rasul said.

"Is he?" I asked.

"Yes, he is," Rasul said smiling.

"I want to visit him then," I said.

"Okay, we'll go before we see Imam Ali," Rasul said, then took a bite of his pita.

My first time wearing an abaya was in Samira's room.

First, I wrapped a hijab around my head. It was the first time I'd worn it outside of the airport. Then I peeked my face through the front hole and slipped my arms through the side openings and wrapped the cloak around me like a blanket.

With my body respectfully covered and my stomach filled with soul food, I went to reunite with my grandfather.

5 Million Graves

Najaf is home to the world's largest cemetery, Wadi-us-Salaam, which means land of peace in English. There are more than 5 million graves resting there.

The sun was starting to set as we pulled in. After driving by thousands of graves, Rasul was able to find a parking spot.

"If you come early enough the burial groundskeepers can point you to any grave you're looking for," Samira said.

On foot, we passed families sitting in wagons pulled by motorcycles. They carried empty plastic gallons in their hands on the way back from visiting loved ones. Their eyes followed us as we made our way through.

"It's rose water," Samira said. "It's tradition to wash the grave with it when you visit."

We didn't have rose water, but Samira remembered to grab a bottle of water from Rasul's car.

"It's somewhere over here," Rasul said leading us through the cemetery's crooks.

The cemetery sits on 1,485 acres of land. Graves are stacked on top of one another with mausoleums in between. Murals depicting loved ones are everywhere.

Rasul pointed at a grave.

"I went to school with that guy," Rasul said.

"How did he die?" I asked.

"He was shot," Rasul said using his hands to imitate a gun.

It was my first time visiting family at a cemetery.

"There it is," Rasul said triumphally.

He climbed over the graves and started to read off the names of buried Sibte family members. Sibte is my father's last name and the name of his family's tribe.

"Jido's first wife is buried over here next to him," Rasul said pointing at different graves. "And his father is buried here. We don't know who this person is, though."

Rasul pointed at a grave that was buried beneath the ground, not above it like the rest. The inscription on the grave was too worn to read.

The grave may remain a mystery.

"We'll probably put a grave on top of it," Rasul said.

'We Brought you a Flower'

Samira opened the bottle of water and spilled it over my grandfather's grave while reciting a prayer to wake him.

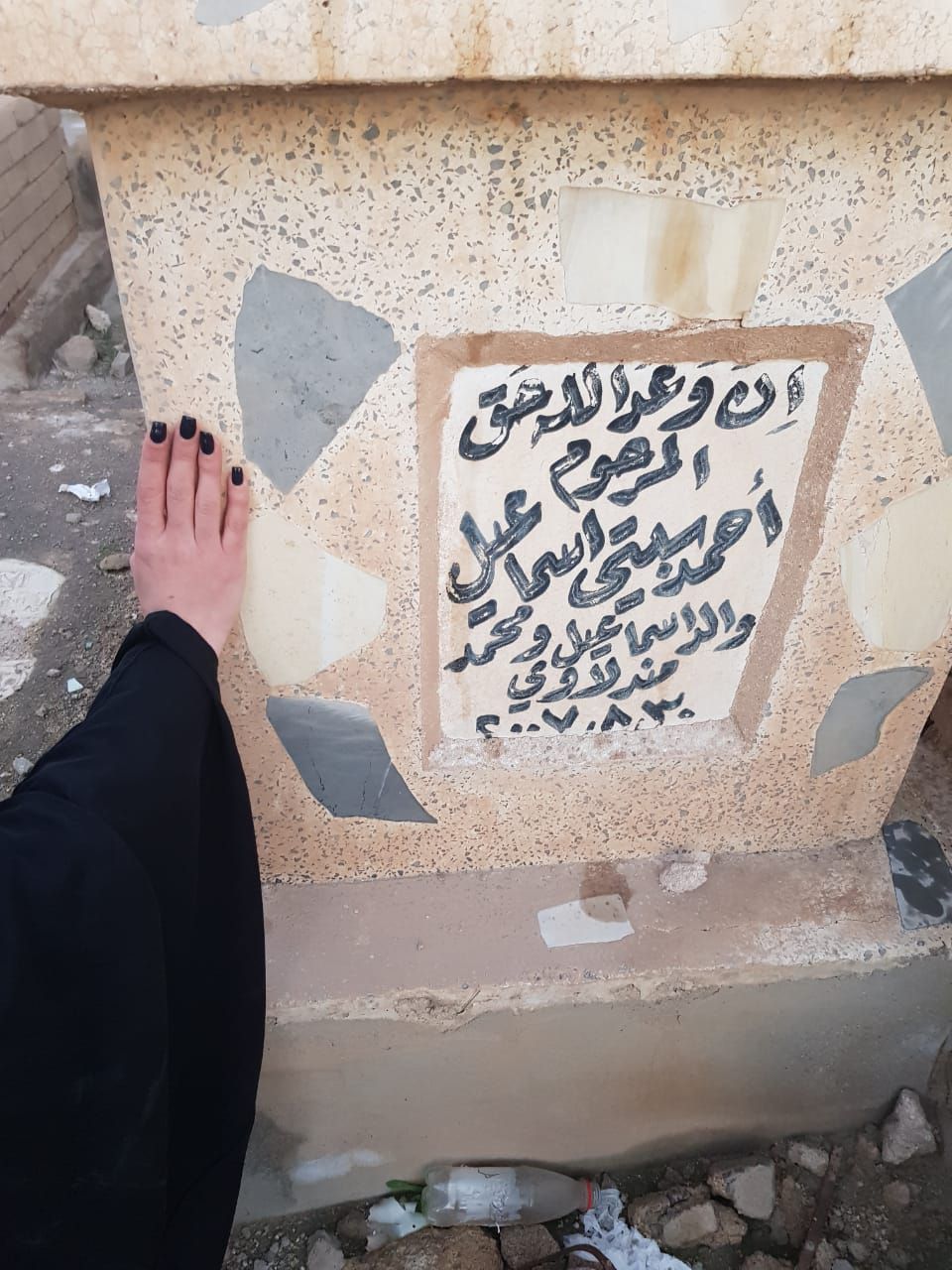

Painted on the front of his grave was his full name, Ahmad Sibte, the date he was born, 1921, and died, 2007, as well as the Sibte tribe he belongs to. Tribalism is still strong in Iraqi culture.

Kneeling on one leg, I placed my hand on the front of my grandfather's grave. Letting out a deep breath, I closed my eyes and introduced myself.

"I am Mohammad's oldest child," I said. "I'm sorry it took me so long to get here."

Samira and Rasul began weeping.

"We brought you a flower today," Rasul said, his hands on his father's grave.

Rasul sobbed heavily. He was out of town when my grandfather passed away. Being unable to say goodbye still weighs on him, Samira said.

I stopped reciting the only prayers I knew to catch my deceased grandfather up on the last two decades. For the first time, I was able to describe to him the tolerant and compassionate man he'd raised, Baba, and my younger siblings. Our conversation ended with the promise that I would bring my siblings to meet him.

Finished, I wiped the tears from my eyes and wished my grandfather a good night. Opening my eyes, I'd noticed the sun had set and it had gotten dark out.

Holding my head up, I looked at the sky. There was a perfect half-moon right above my grandfather's grave.

Am I Broken?

A large golden Dubba, or dome, in between two tall golden minarets marked Imam Ali's tomb. The dome is made of 7,777 gold-plated bricks. Handmade deep-sea blue, turquoise and white ceramic tiles piece together Quran verses lining the mosque's walls. Gold-plated domed archways were our gateways into the mosque.

The courtyard inside was crowded with people of all ages walking, talking or sitting down with their families. About 8 million people make the pilgrimage to the Imam Ali's mosque. Imam Ali's influence extends beyond Islam, however.

The United Nations declared Imam Ali the fairest governor in all of human history in 2002. He was Prophet Mohammad's cousin and is documented to have been a model of good governance. In its declaration, the U.N. cites six examples of a good governor as written by Imam Ali in a letter to Malik Ashtar who he appointed as Egypt's ruler in 656 A.D.

A good leader is modest, fair, accepting of religious beliefs aside from their own, surrounds themselves with virtuous, honest people, seeks company of the wise, continually educates themselves, remains undeterred by difficulties and develops land rather than collects taxes.

"There are Muslims that will go their whole lives without visiting the Imams," Samira said.

Samira and I stood in line with our shoes and phones in our hands. We weren't allowed to have them inside. The man at the window I approached ushered at the top of my forehead.

"Sister, your hair is peeking out. You're visiting the Imam," the man said.

He was the second person in the span of 15 minutes to point out the hair peeking from my hijab.

"I'm wearing a hijab and an abaya. How much more covered up can I be?" I replied holding my shoes up.

The man rolled his eyes at me but took the shoes regardless.

Rasul told Samira and I to meet him in the center of the courtyard once we finished our visitations. Women and men had separate spaces leading to their area of visitation. Holding my abaya around me like a blanket, I walked beside Samira toward Imam Ali's tomb. Opened giant wooden doors encased in hard plastic guided us into the women's visitation area. Samira kissed the door before we entered and told me to do the same.

Inside, hundreds of women in black abayas surrounded the tomb. Some sat down with opened Qurans in their laps and prayer beads in their hands as they recited verses with their eyes closed. Others had their prayer rugs rolled out while they stood with their palms toward the sky. They were reciting dua, prayers requesting their families and loved ones good health, relief of illness or well fortune.

"Hold my hand," Samira said as we approached the golden gates encasing Imam Ali's tomb.

Women standing on chairs waved green feather-ended sticks to direct the crowd of visitors.

It took nearly an hour to reach the golden gates guarding Imam Ali. Old women, young mothers holding babies and children were elbowing each other aggressively toward the gate. Nearly all of them were crying while reciting duas aloud.

"Let her get to the front, it's her first time visiting," Samira yelled at the woman pushing her body in front of mine.

Once my fingers touched the gates of Imam Ali's tomb, I quickly paid my respects and tore myself away. I didn't feel anything. In that moment I felt ashamed for being unable to feel something.

The ride to Samira's house was quiet. My eyes were glazed over.

My younger brother, Ali, was named after the Imam Ali and I was named after his wife, Fatima Zahra. Baba, a Shi'ite, believes Imam Ali is the rightful successor of the Prophet Mohammad.

Both of my parents are Muslim, but Baba is a devout believer. Allah, the Prophet Mohammad and the Imams have always seen Baba through. Speaking as his daughter, I think religion is a pillar of unconditional support for Baba. My visit to the Imam Ali was a show of support toward a core part of Baba's life. Religion was something I wanted to share with him.

Once we'd gotten back, I decided to take a moment to myself in Samira's room.

Sitting on her bed, I pulled my phone out and called Baba.

"How do you feel after visiting the Imam?" Baba asked.

I broke down, sobbing on the phone.

"It's OK," Baba reassured me. "It's good to cry. Sometimes you need to cry."