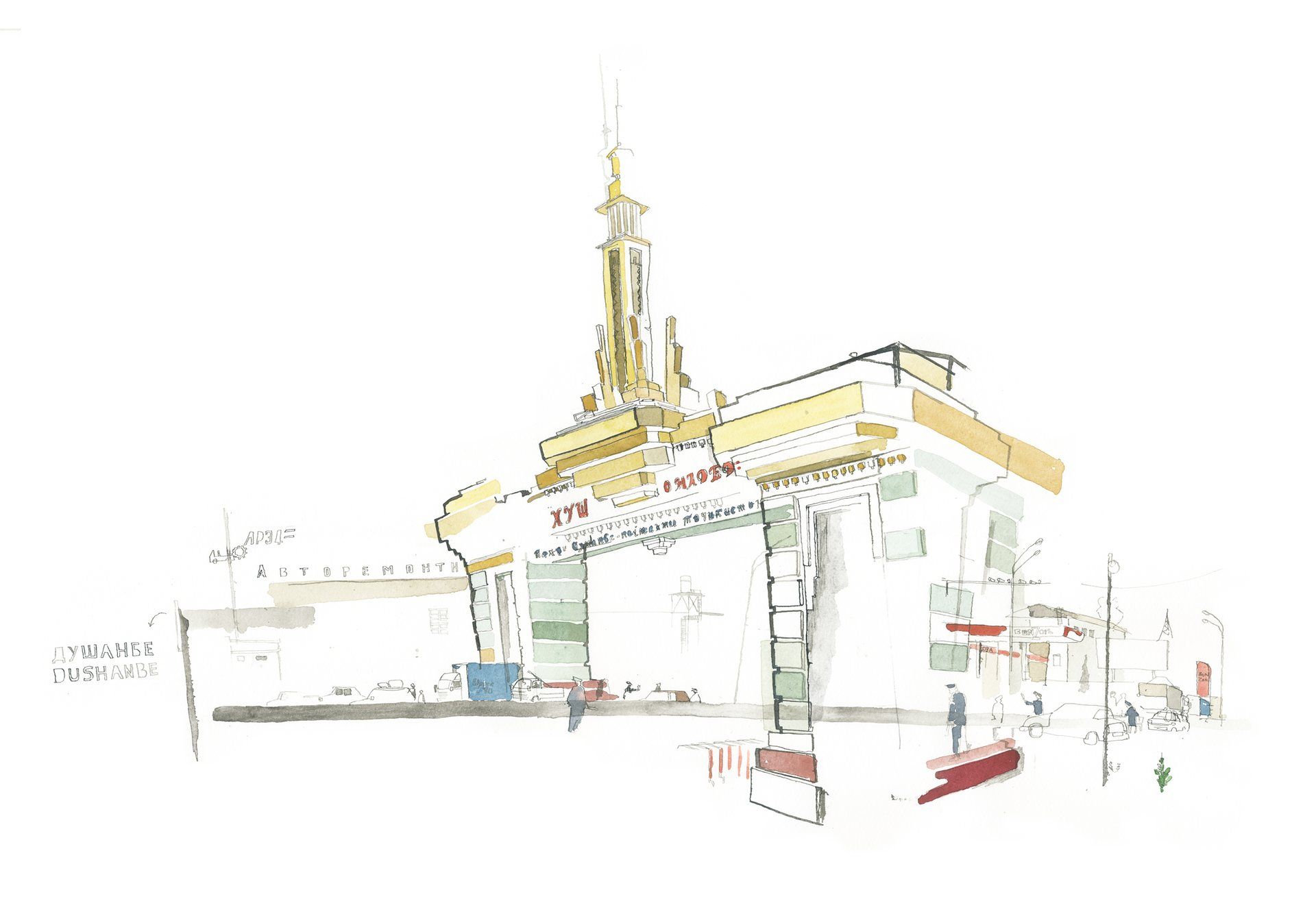

The twice-weekly train ride from Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, to Moscow takes four days and traverses the whole of Central Asia. Tajikistan depends on labour migration more than any other country in the world, and these carriages are full of migrants–nearly all of them men, traveling to Russia for work. They chat about the employment they might find, the state of the Russian economy, the harassment by Russian police that they are almost certain to face. Some talk about Islam, while others, now old hands at this journey, sit quietly, sleep when they can, and wait.

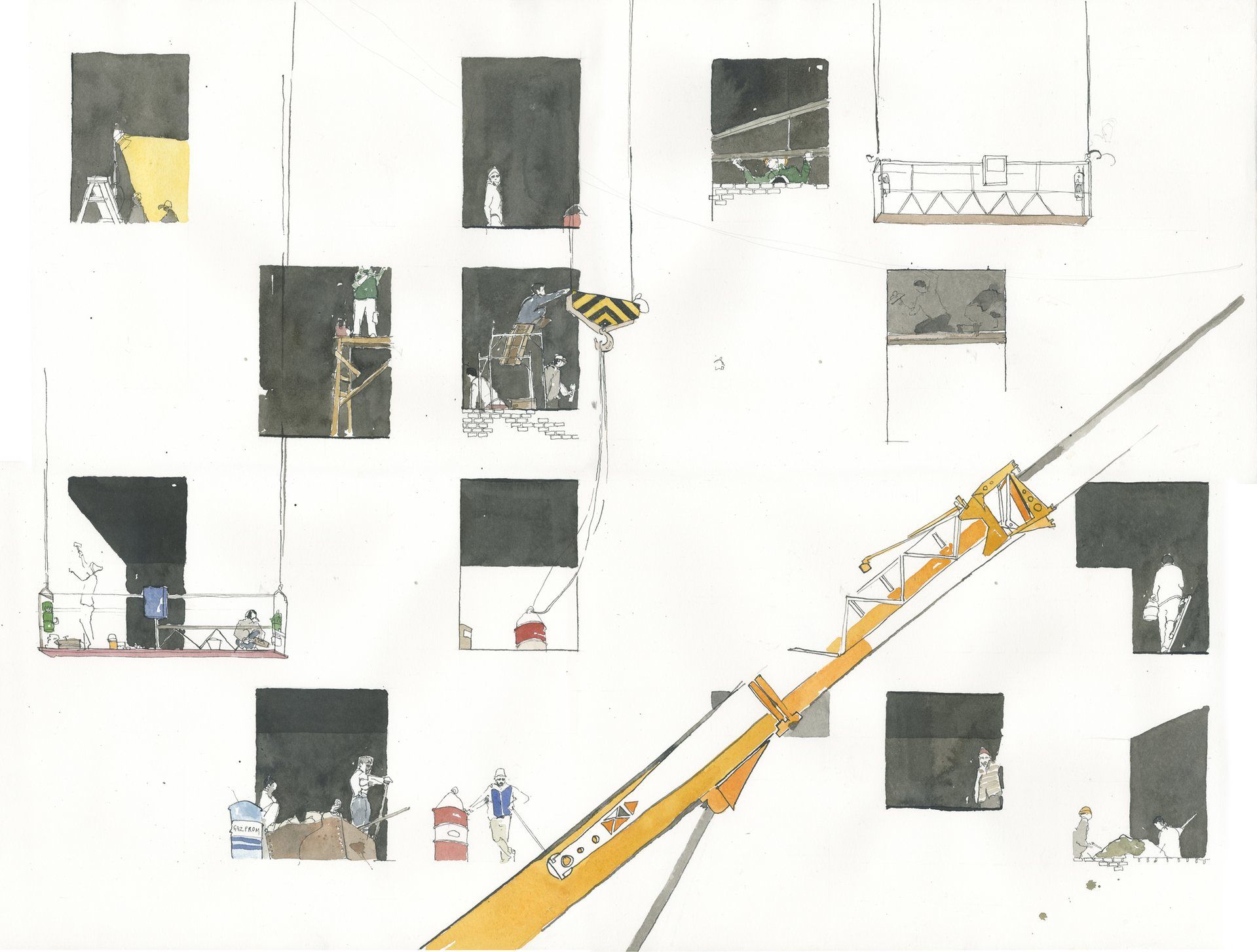

For this project, we spent three weeks documenting the realities of rural Tajikistan, the journey to Russia, and the situations the migrants find themselves in when they finally arrive. In the past year, global oil prices have fallen and the Russian economy has suffered. New visa regulations have also suddenly made many migrants vulnerable to deportation. For the men on the train, their new lives will be precarious and filled with menace, but at least there is the chance of a job…