At first glance, César Portocarrero’s home office looked like the epitome of a researcher’s work space. Books covered two of his walls, framed certificates hung along another, and a first-floor window barred with thin iron columns looked out onto a busy street in Huaraz, Perú. After speaking with César, however, it was clear that his office did not belong to any ordinary researcher.

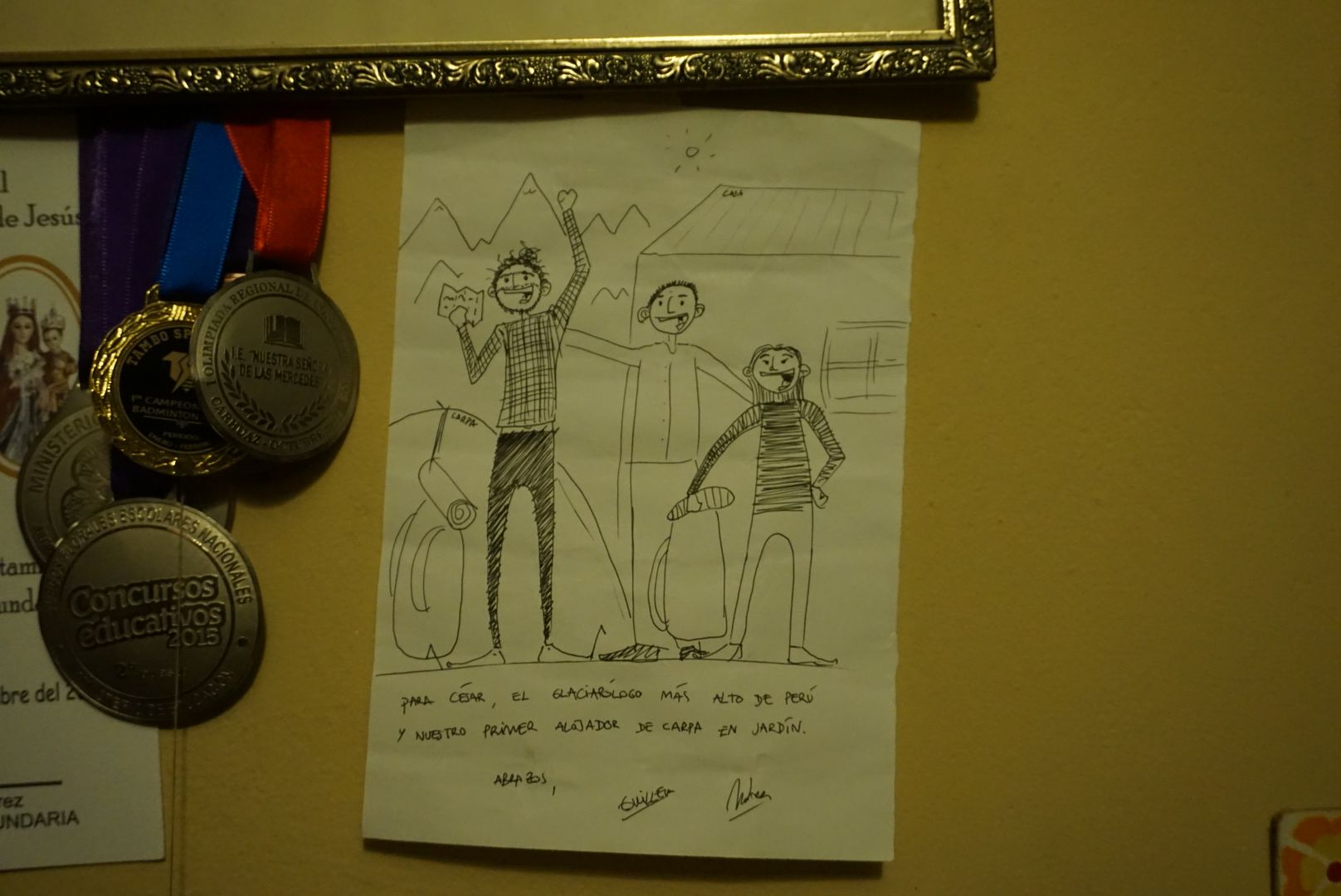

Catching me examining medals displayed on his wall of accolades, César pointed to the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal and explained that he was awarded the medal in 2016 to recognize his lifelong work in mitigating flood risks in the Andes and Himalayas. César didn’t mention that the medal is the world’s most prestigious award for mountain advocacy. Since the early 1970s, the glaciologist and engineer has worked on protecting countless mountains, people and wildlife all over the world.

I met with César on my second night in Huaraz. With the assistance of a cane, he welcomed me at the gate outside his garden. Despite his fluency in English and Spanish, before I began recording our conversation, César smiled, prompting wrinkles that looked like river tributaries to appear around his eyes. He told me that we should do the interview in Spanish so that I could practice. I imagined we would spend most of our time discussing Lake Palcacocha, the glacial lake, and flood risk that lies above Huaraz, the center of my reporting in Perú—or so I thought.

A major driver of climate change, rising global temperature is causing glacial ice to thaw more quickly than it usually does during the warmer parts of the year. In turn, glacial water is staying in its liquid form, expanding mountain lakes and increasing the chances of glacial pieces falling into the bodies of water that they feed. “Glaciers are disappearing,” César said. “In many areas of the Andes, they’ve disappeared completely.” Should a large block of ice looming beside the lake break from the glacier and fall into the water, the inhabitants of Huaraz would only have 30 minutes to evacuate the city before it was flooded.

César was clear that, while drainage pipes were installed to prevent the lake from expanding, Lake Palcacocha’s water level is too high. Lake Palcacocha “needs to be lowered by 20 meters.” Motioning to a paper scroll on top of the bookshelf behind me, he said, “I have a complete project to [lower the lake]...with maps and everything...but the authorities didn’t accept this.” Despite his globally-acknowledged expertise, César’s power has its limits.

César said that some politicians understand the dangers of Lake Palcacocha and climate change as a whole, while others completely disregard it. In both cases however, politicians rarely act to mitigate and prevent consequences. Lack of action isn’t unique to the Peruvian government; César cited Nathaniel Rich’s narrative in The New York Times Magazine about the United States government’s knowledge of the dangers of climate change in the 1980s and its subsequent inaction.

Specific dynamics in Perú, however, complicate the government’s complacency when it comes to climate change. Huaraz is part of the Ancash region, of which the majority of the population lives on the coast. Thus, it is this same population that elects representatives who cater to their coastal constituents rather than to people like César. While the regional government might recruit César to assess risk and share his research, there is political pushback: “It doesn’t interest [the government] to work on this...they have the last say,” he says.

The Peruvian government “wants tangible things like [other governments do] in every part of the world.” Authorities view the threat of a flood, rather than the presence of one, as too abstract and long-term. César’s plans outline strategies for Disaster Risk Management, most notably, how to lower the level of Lake Palcacocha so that should a chunk of ice crash into it, the city of Huaraz would be safe.

César added that while Lake Palcacocha is dangerous in isolation, the lake is also representative of a host of water-related threats to the region: “In reality, the biggest problem for humanity will be decreasing water sources.” César’s eyes scanned the bookshelf closest to his desk and reached for a book that chronicles “how civilizations all over the world disappeared because of lack of water.” César continued, “we have and are going to have a water crisis.”

A global water cycle altered by climate change will bring drought in addition to flood. There will be more illnesses, less crop production, more use of insecticides and pesticides, just to name a few of the devastating consequences. César again swiped a book from his shelf. He held up James Hansen’s Storms of My Grandchildren, saying, “if we don’t act, we are going to pass on huge problems...and this is immoral.”

Ultimately, “the term climate change is soft.” César says, “we need to make people worry...to call it a climate emergency...a climate crisis.”

“No hay mucho tiempo.” There isn’t much time.