Ten years after the Ethiopian famine of 2003, when international food aid rushed in to feed 14 million people, another World Food Program (WFP) tent has been erected on an open field. But this isn’t a scene of food distribution. It is a scene of food purchase.

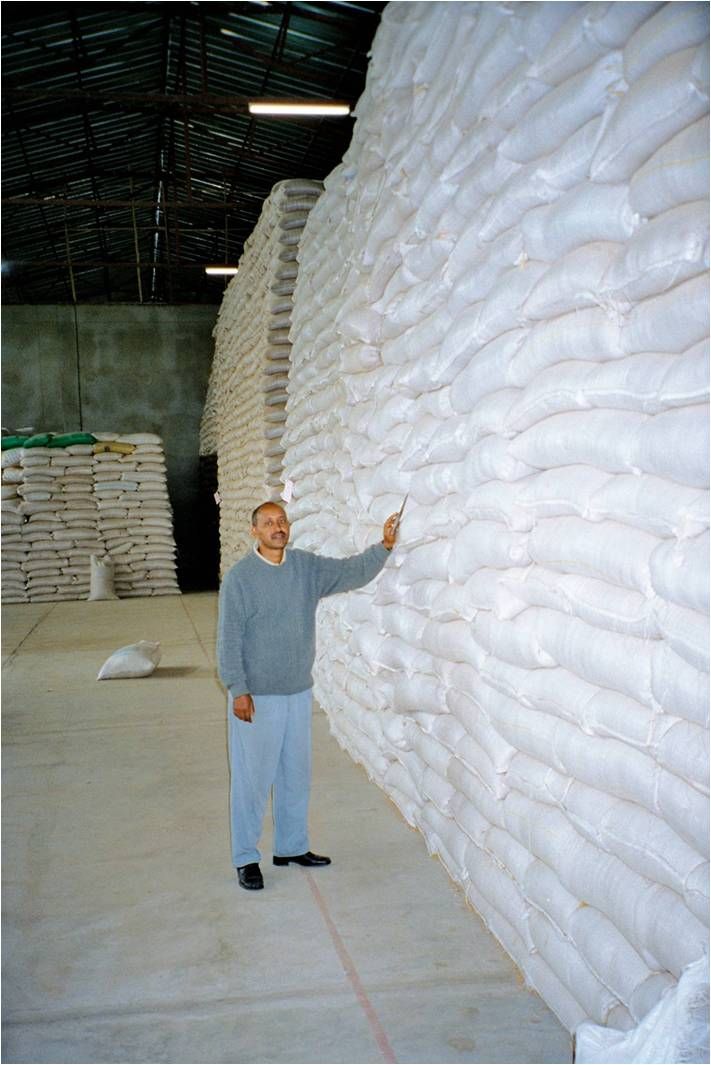

The action happens on the grounds of the Sidama Elto Farmers’ Cooperative Union in Awassa, Ethiopia. Sidama Elto is one of 16 cooperative unions in Ethiopia that have signed forward contracts with the WFP for the purchase of more than 28,000 metric tons of maize grown by their smallholder farmer members. The maize, which is part of 112,000 tons of food the WFP purchased in Ethiopia last year, will be used for WFP relief distributions in the country. Ten years ago, many of those farmers and their families were receiving food aid from the WFP.

One of the major lessons in agricultural development over the past decade is this: Markets Matter. The 2003 famine tragically, and incomprehensibly, followed two years of bumper harvests in Ethiopia. The surplus production overwhelmed the country’s weak and inefficient markets. There were no export channels; the domestic market’s ability to absorb the harvests was crippled by woeful infrastructure. The food piled up on farms and prices collapsed, upwards of 80 percent in some areas. Farmers lost incentive to plant the next year. Then the drought hit, and feast turned to famine. The markets had failed before the weather did.

That gobsmacking turnaround triggered a reversal of the neglect of agricultural development that had set in since the 1980s, as I noted in my TedxChange talk last month. In the past decade, science and research geared toward improving the work of smallholder farmers (who produce the majority of the food grown in the developing world) have been reinvigorated; so too have trade and business efforts accelerated to provide greater market incentives and opportunities for the farmers. Prior to 2003, boosting agricultural production – growing more food — was the primary focus and developing markets was considered to be a “second-generation problem.” Now, markets share top billing with production, as it should; markets provide incentive to produce more.

In Ethiopia, it started with the creation of the Ethiopia Commodity Exchange in the wake of the famine. Now, the mantra spreads, in radio dramas, government pronouncements, business negotiations: If you grow it, someone will buy it.

The WFP’s partnership with Sidama Elto is part of its Purchase for Progress (P4P) program, which uses the WFP’s purchasing power to create markets for smallholder farmers. Supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and implemented in collaboration with the government of Ethiopia through the Agricultural Transformation Agency (ATA), P4P works with the farmers to improve the quality of their crops and the post-harvest handling. Simiret Simeno, deputy manager of Sidama Elto, says that for the first time its 13,000 farmer members see that better quality can bring better prices. And they can also see their contribution to healthier communities, as one of the markets is an expanding network of school feeding programs supplied by locally grown crops rather than food being shipped in from abroad.

The ultimate goal of the WFP purchases is to demonstrate to commercial buyers that smallholder farmers can reliably produce high-quality food worthy of their business. Sustainable success here could also bear witness to the potential impact of President Obama’s proposed food aid reform, which would allow for nearly half of the U.S. food aid budget to be used to buy food nearer to the hunger crises – providing markets for smallholder farmers — rather than shipping it all the way from American farms (as has been the U.S. policy for decades).

These public-private ventures bring both maturity and modernization to markets that hadn’t changed much for centuries. Working with local banks and donor governments, P4P has introduced forward contracts to participating cooperatives and smallholder farmers. The ATA has also been crafting links between farmers and commercial buyers of several crops, like teff, barley, sesame and chickpeas.

Above all, says Khalid Bomba, the chief executive officer of ATA, “Smallholder farmers need confidence that there will be buyers for what they grow.”

And confidence that the misery of 2003 – the misery of failed markets — won’t happen again.