See the full multimedia presentation on Mashable.com

In the 1840s, the Canadian government established the Indian Residential School system, a network of church-run boarding schools created to forcibly assimilate indigenous children into the dominant culture of Canada.

The children who attended these facilities — coming from First Nations, Métis and Inuit communities — were punished for speaking their native languages or observing indigenous traditions. They were routinely physically and sexually abused, both by the teachers who ran the schools and by older students who had typically been assaulted themselves. In some extreme instances, students were subjected to medical experimentation and sterilization by teachers and school administrators.

The last residential school didn’t close until 1996. The Canadian government issued its first formal apology in 2008.

Still, the lasting impact on Canada's indigenous populations is immeasurable. At least 4,000 children died while in the system — so many that it became common for residential schools to have their own cemeteries.

Those who did survive, deprived of their families and their own cultural identities, became part of a series of lost generations. Languages died out; sacred ceremonies were suppressed and even criminalized. First Nations elders have called the residential school system’s practices a cultural genocide.

In the fall of 2014, I spent a month documenting the school system’s terrible legacy through photography. Much of this project focuses on the literal impact of what it means to lose one’s identity. A disproportionate number of residential school survivors and their immediate families struggle with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and substance abuse. First Nations peoples are also excessively marginalized in the public health system, and at least 1,200 aboriginal women have been reported missing or murdered over the past 30 years, further highlighting the well-being gap between indigenous and non-indigenous people.

The social injustices that continue to affect Canada’s native populations need to be recorded and shared in order to prompt change.

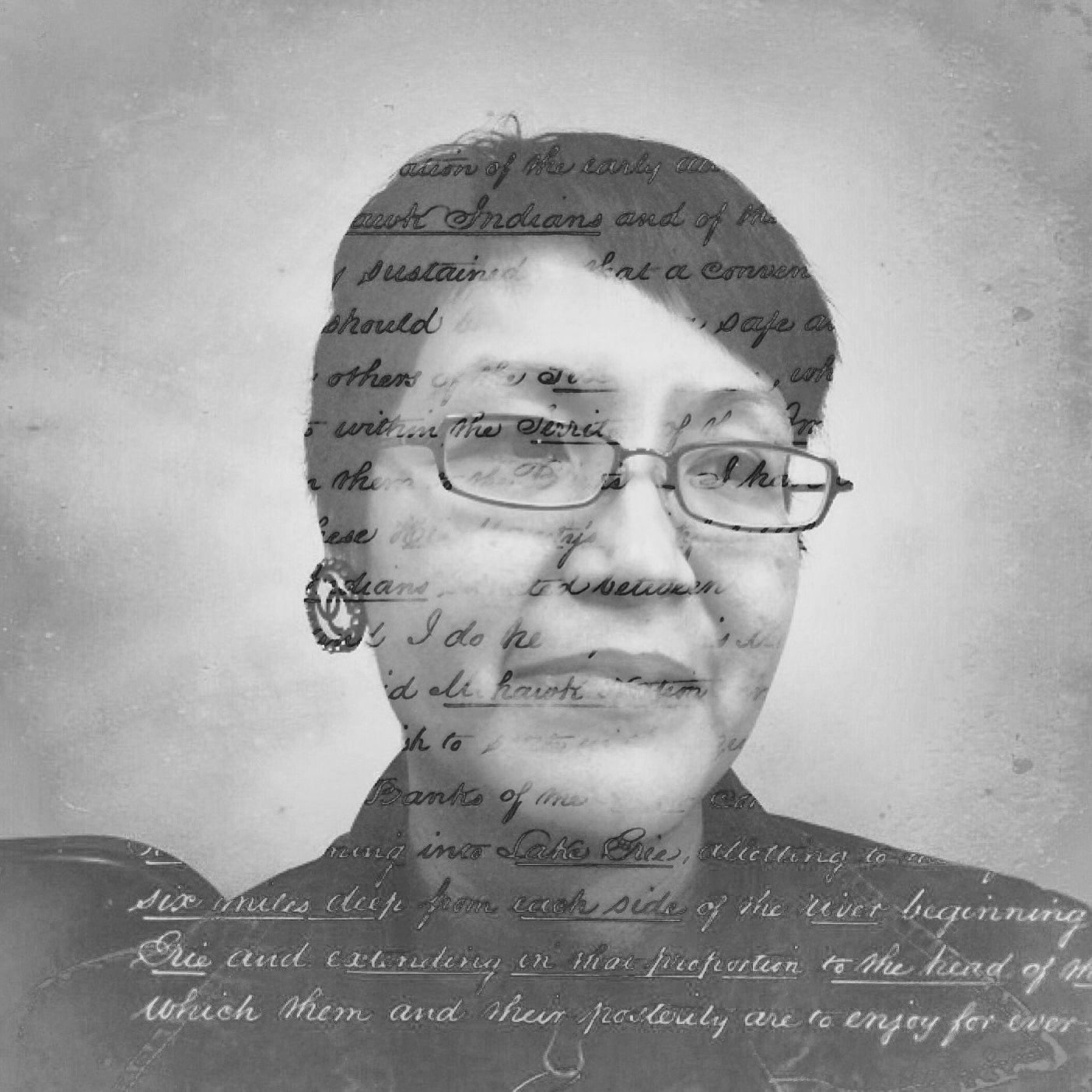

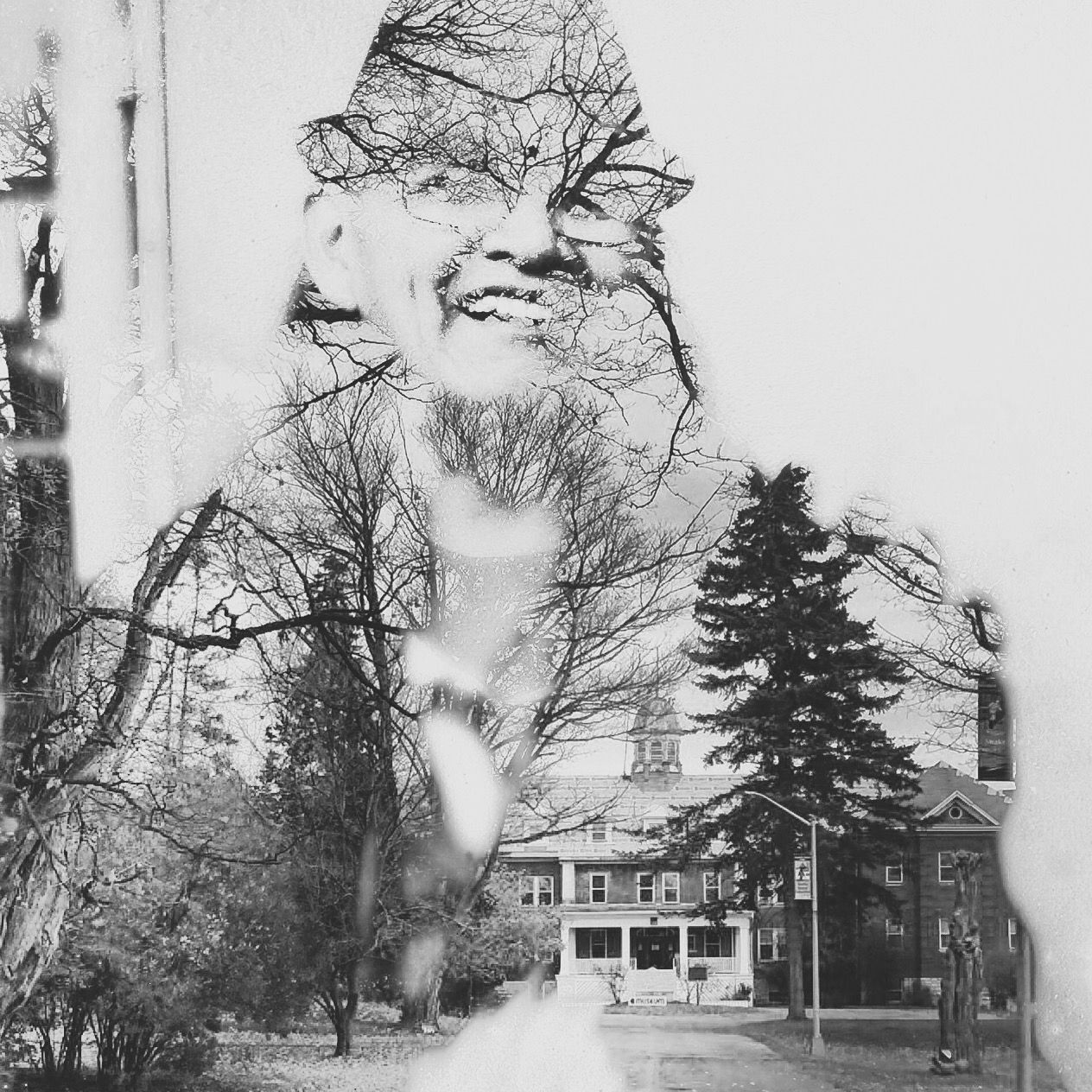

But one of the many problems with images depicting drug use, alcoholism and poverty is that they can do more to shame and stigmatize the subjects than shed light on the sources of their suffering. In an attempt to overcome that challenge, I created multiple-exposure portraits to look at the causes, rather than the effects.

I paired individuals with sites where residential schools once stood, government documents that enforced strategic assimilation and places where First Nations peoples now struggle to persevere. Each double exposure contains an echo of trauma, which lingers even during the healing process, as languages and traditions return.

Most importantly, these images are meant to not only reveal the past, but also to look to the future — one in which Canada's indigenous peoples can hopefully find peace.