The Peruvian government announced last month that it would attempt to help and potentially contact an isolated indigenous tribe that lives deep in the Amazon. The tribe has been sighted more and more frequently, and its members have killed two local villagers. But some fear the plan could further jeopardize the group, and on 3 August the government backtracked on the implications of its announcement, insisting that it would not make the first move toward official contact.

The case highlights an ongoing international debate about how to best help emerging tribes, who lack immunity to common diseases and are among the most vulnerable people on the planet (Science, 5 June, p. 1072). "We are extremely worried about this situation and its possible disastrous consequences," says Francisco Estremadoyro, director of Lima-based ProPurus, a nonprofit organization that seeks to protect isolated peoples and the environment in eastern Peru.

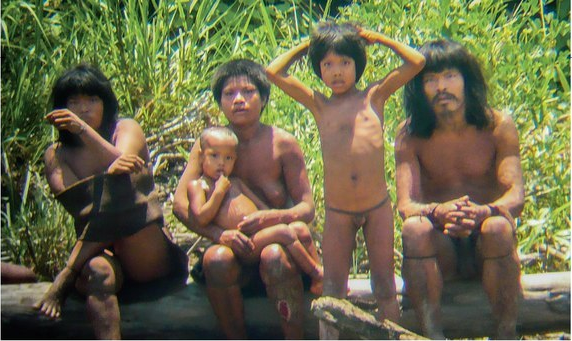

He and others are concerned about 30 members of the Mashco Piro tribe in Manu National Park, a remote forested area bordered by the Madre de Dios River. Peruvian policy is to avoid all contact with such isolated tribes and protect them from intruders on their reserves. But in practice this policy is difficult to carry out.

Anthropologists report more than 100 sightings of these tribespeople since 2014. The Mascho Piro raided a nearby village for machetes and goods and killed two villagers, the most recent in May. In past months they have also repeatedly gestured at, called to, and received goods from local people. Tour operators sell tickets for "human safaris" along the river, and missionaries are reported to have given food and clothing to the group in the past year. "You can see a group on the beaches for hours, waiting for the boats to pass," writes Luis Felipe Torres, and Peruvian ministry anthropologist who has spent time in the area, in an essay published 22 July. "They are especially interested in bananas, cassava, sugarcane, machetes, and pots." Torres concludes that "they are deliberately seeking to interact with people transiting the river."

Given such credible reports, "there are no reasonable grounds to interpret this behavior as a sign that this group wants to remain unconnected to the rest of society," said Patricia Palacios Balbuena, vice minister in Lima's Ministry of Culture that oversees tribal affairs, in a 21 July statement. The ministry subsequently approved a 6-month plan to increase patrols, discourage raids, and make contact with the Mashco Piro "only if they make an appearance and show a willingness for a conversation." But a ministry official also told reporters that the government planned "controlled contact," raising concerns among some nonprofit groups.

When and how to make contact with isolated tribes is a hotly contested issue. Anthropologists Kim Hill of Arizona State University, Phoenix, and Robert Walker of the University of Missouri, Columbia, recently proposed in an editorial (Science, 5 June, p. 1061) that "a well-designed contact can be quite safe," but the nonprofit group Survival International in London accused them of promulgating a "dangerous and misleading" idea. Without medical care, isolated tribes can be all but wiped out by the flu or other diseases.

In the Mashco Piro's case, given the contact already occurring, infection is likely, officials say. In the initial announcement, Balbuena called for "immediate action by the competent authorities to safeguard their health and prevent negative consequences of uncontrolled contact."

But Survival International and ProPurus protested Balbuena's statement and the vague plan, fearing that it could set a dangerous precedent. Rebecca Spooner, campaigns officer at Survival International, insists that the Mashco Piro's conflicting actions leave their desires unclear. Although tribe members may have sought goods, "shooting arrows at people is a clear indication that they do not want contact." Official contact without a request is illegal, she says. She urges Peru to focus on keeping outsiders off the reserves.

Hill counters that "leaving the Mashco Piro alone will ultimately bring a terrible disaster to them," and calls the Peruvian government's intention to act "good news." But he warns that preventing epidemics among the group will require a commitment longer than the planned 6 months. Tribe members "cannot be left alone, even for a few weeks, during the first 2 to 3 years, or the whole population could go down," he says. Estremadoyro agrees, and worries that the government lacks the political and financial support to provide long-term food, shelter, medical help, and other services.

All agree that the situation is now a crisis. The government has "reacted far, far too late," Spooner says. She blames officials for failing to keep loggers, missionaries, and tourists off the Mashco Piro's land, which she says is at the root of the tribe's frequent appearances on the river. The government report suggests that outsiders are poaching animals such as peccary and tapir, which are staple foods for isolated people.

The ministry's August statement promises to patrol the river and train locals to avoid isolated people unless the tribe makes the first move. Assisting the Mashco Piro "is a huge challenge that cannot be postponed," Balbuena says.