The Oro family has lived on farms in the Cordillera Blanca mountains para siempre, forever. The land is so ingrained in their existence that Clinton Oro, the son of Gabino Raúl Oro Chávez and Dorotea Cirilo Milla, can find his family’s adobe home—a one-hour uphill hike from the nearest town of Santa Ana—even after the sun hides behind the mountains and the only light he uses to guide him comes from the moon.

Andean farmers like Gabino have a bird’s eye view of the nearby valley city of Santa Ana. From their land, they gaze at gravel-colored mountain peaks that once had snow, plots of dusty soil, and smoke weaving in and out of patches of eucalyptus trees as farmers burn their land for a new season of crops. The agricultural technique quickly and cheaply clears excess vegetation for a new farming season, but even when contained, the practice is problematic—it releases carbon into the atmosphere and contributes to the very crisis the same group suffers from but often doesn’t name: climate change.

“When I was a child,” Gabino said, “there was plenty of water and more glaciers.” A frequent observation among rural farmers and city-dwellers alike is that hot weather is getting hotter and cold weather is getting colder. Changing water cycles is causing drought and flooding; Gabino said that “harvests are in chaos.”

The absence of the term cambio climático, climate change, in Gabino’s description of the phenomenon does not signify that families like the Oros do not grasp what the term means. They know it intimately—they live its effects. When speaking to Gabino and Dorotea, they unequivocally describe climate change through lived observations rather than through theory. This is a product of limited education, language barriers (many rural Peruvians like Dorotea speak Indigenous languages like Quechua), and little political power.

Peru’s legislative landscape is difficult to navigate—the country is comprised of 25 regions, each divided into provinces with even smaller districts. The Oros live in a village called Yungay Pampa within the Santa Cruz district and inside the Huayas province, which is one of 20 provinces of the Ancash region. Often, the local government is most familiar with the obstacles for which constituents lack the political power and financial recourses to fix.

Local official Jorge Almarchaz Paulino is the Technical Secretary of Risk Management and Disaster Control in the Santa Cruz District—which was declared an emergency zone in 2011 after a lake flooded, killing livestock, destroying powerlines and roadways, and isolating rural communities for weeks. Santa Cruz has maintained this emergency classification ever since.

Jorge noted that his municipality has requested funds from the regional government, but there is always “great delay.” What’s more, the majority of Ancash representatives focus their careers on the priorities of coastal areas—rather than to the needs mountainous regions—which comprise a greater proportion of their constituents.

Jorge said that unreliable canals and sources of potable water in the district mean that “some days there is water, some days there is not.” Sand and debris can prevent water from flowing from the river outlets, leaving people downstream without it. Some communities who live above man-made canals rely on rain to sustain themselves and their crops. But irregular rain patterns, a consequence of climate change, mean that families can easily “lose it all.” Gabino said that it used to rain six months out of the year, whereas now it “rains only three months at the most.”

As Gabino flipped through a large record keeping book, the wicker stitching in his chair let out quiet creaks. He stopped at a page, his finger running along a pencil-written sequence of dates and notes. Looking up, Gabino recalled a government-sponsored initiative to build canals to homes and villages in the region. Consulting his book again, Gabino said that the work began in 2011, progressed for six months and then ended, unfinished.

According to Gabino, officials at Huascaran National Park, the entity overseeing the project, suspended the development because the construction would block a central road on the mountain where families like the Oros live. Gabino was told that there was “bureaucratic holdup.” When I brought up this case from eight years ago to Willian Martínez Finquin, the director of Huascarán National Park phoned his secretary to search for records of this development in Gabino’s mountain village. While she searched through the archives, Willian and I spoke about the park’s role in development, such as the canal about which Gabino had spoken.

What I realized is that the original question I posed to Willian about the Park’s involvement in the canal project was fundamentally flawed—the Park does not have the power to physically construct any project. Instead, they authorize other government agencies or local communities to do so. No records were found of the canal development, and there’s no easy way to track down what happened and who caused the collapse of the initiative.

Gabino’s understanding of the onus of failed or incomplete government initiatives in his village illustrates how disorganized agencies create a system of misinformation and ultimately force the responsibilities of adoptive strategies on individual families. In the following installments of this project, I will further explore this clash between formalized agencies and local communities.

In an attempt to salvage their plot of grain, the Oros built a raised reservorio (reservoir) to capture glacial water. At the base of the open stone tank is a valve that Gabino opens when there’s a water shortage. Reservoirs are only for the corto plazo, the short term. Once glacial ice melts completely, there will be no water source to later store.

Due to this geographical disconnection between lawmakers and the people they represent, there is also a dispute over the definition of “disaster.”

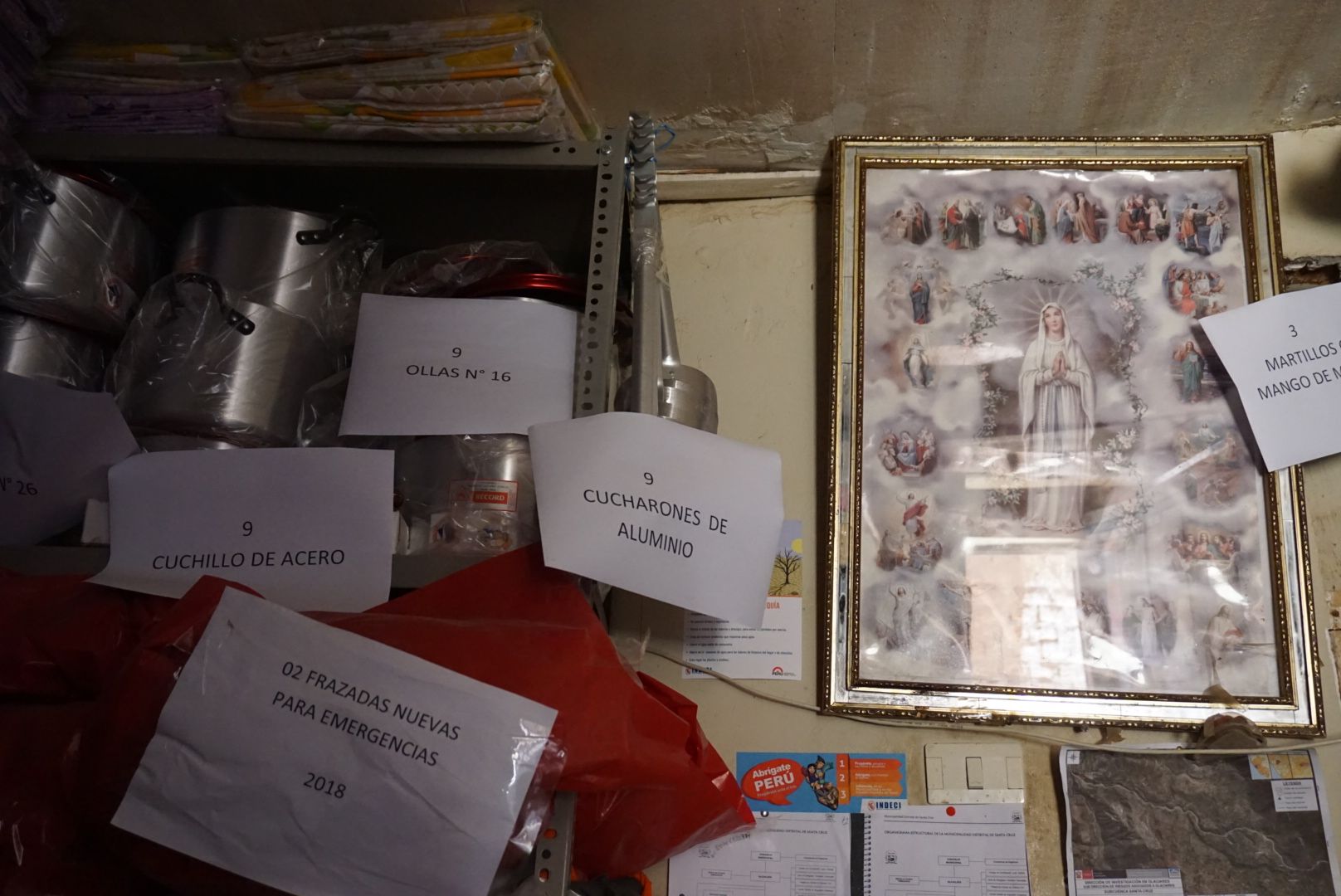

Jorge said that regional representatives “tell [them,] ‘there must be a disaster for you to hand out any aid ... this is not a disaster.’” The government’s version of disaster translates into a skewed version of prevention. They aim to act once a disaster like a flood strikes—once it’s too late. “They should invest in prevention,” Jorge said.

But people who live the effects of climate change experience the symptoms of current and future disaster. Recalling the cold temperatures that Gabino cited, Jorge said that children, especially those from families of few means, are suffering health consequences. “We requested a package of warm clothes [coats], and we have not received a response. Animals die, harvests are meager or non-existent.”

For families like the Oros, climate change is exacerbating their financial challenges and, while they need potable water, they also need resources like blankets for increasingly colder temperatures. There’s a constant battle between allocating resources for long-term prevention and securing resources for today, or tonight.

The Oros are intent on preserving their livelihoods with the resources they have. Clinton and Gabino built a small reservoir on an upper section of their land to capture glacial water so that their diminishing trigo (wheat) production could at least have a water source. Gabino knows that while he and his family see the effects of climate change in their daily lives, people in the cities and towns of the valley feel the consequences as well: “We are all affected.” Cities like Huaraz are sustained with food products from the countryside, and Gabino stressed that “if the countryside does not produce, you cannot function, no matter how much money you have.”

In addition to smaller harvests, more extreme temperatures are breeding stronger strains of pests which require the use of pesticides and fungicides. In an attempt to resurrect their diminishing harvests, 20 years ago, the Oro family started to use these chemicals after seeing that their “neighbors were getting better harvests.” Pests grow immune, however and “nowadays, the results are not as positive as before.”

“When I was a child,” Gabino said, “we could harvest without the use of fertilizers.” Not only are people and animals getting ill from the use of these harsh chemicals, but people like Gabino’s grandmother who did not use “poison to cultivate her land” are becoming ill from the chemicals in processed foods that are replacing the once-organic Andean diet. “Now [people] get cancer, gastritis … a result of drinking soda. We are aging more quickly, not like it was before.”

It sounds like a disaster.