Dharavi looms ever larger in the popular consciousness of Mumbai. Once a tiny fishing village on the edge of the city, it is now home to upwards of one million people seeking the economic opportunities promised by life in the heart of India’s financial capital.

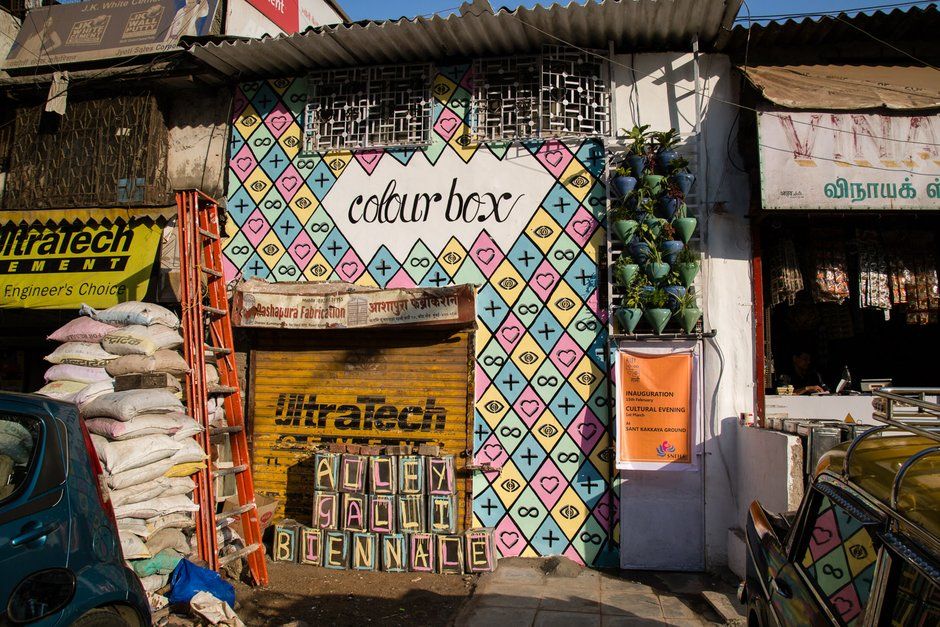

More recently, Dharavi is also trying to shed its image, so often reinforced by depictions in media and films such as Slumdog Millionaire, as a downtrodden slum. The second edition of the ambitious Dharavi Biennale is catalyzing such efforts through art, design, and performance.

Organized by the Society for Nutrition, Education and Health Action, and running through March 7*, the Dharavi Biennale is largely driven by engagement with locals. Organizers are trying to buck the trend of many biennials around the world that largely ignore connections to surrounding communities. Architects Prakriti Shukla and Venkat Ashok, who constructed furniture for their installation by salvaging or “upcycling” found materials, worked with Dharavi craftsmen for over a month leading up to its opening on February 15.

“We were always interested and amazed in the way Dharavi functions as a unit. It’s a self-sufficient community,” says Ashok. “We interacted with Dharavi in terms of trying to reconstruct, rebuild, and better understand the situation that is Dharavi.”

About 80 percent of Mumbai’s plastic waste passes through Dharavi. Recycling, along with a number of cottage industries, contributes an estimated $650 million annually to the local economy. Both architects emphasize that Mumbai would quickly end up buried under its own waste if it wasn’t for Dharavi.

Three event locations house much of the art scattered amid the labyrinthine streets of Dharavi, but emphasis is also being placed on performances, workshops, and screenings delving into a range of topics such as sexuality, sustainability, domestic violence, sanitation, and social justice. Artist Hetal Shukla devised a tryptic of sculptures to celebrate the “genius” of Dharavi.

“The whole concept of Dharavi is growing in people’s mind,” he says. “People used to be a little snobbish about traveling this way. From a slum category it’s shifting into a kind of cool thing. This is a really important type of event because it’s brought two classes together that you otherwise don’t find.”

All good intentions aside, SNEHA is still concerned with how to measure the qualitative impact of these artistic activities throughout the biennial. Dharavi struggles to sustain sanitation and safety improvements despite longterm engagement with welfare organizations. The improvised nature of housing and industries in the area does not lend itself very well to outside interventions or rehabilitation efforts.

Organizers hope that the biennial can serve as inspiration for creative interventions and empower more residents to take greater personal stakes in improving their community. Otherwise, Dharavi risks succumbing to the same fate as other central slums in Mumbai, where developers are bidding to bulldoze entire neighborhoods in order to capitalize on skyrocketing land values. There's a sense that dynamic Dharavi stands a better chance than most of avoiding being subsumed by an increasingly homogenized urban fabric of high-rises.

CORRECTION FROM CITYLAB: This story originally stated that the Dharavi Biennale runs through March 1. While the last scheduled event is March 1, the Biennale exhibitions are actually open through March 7.