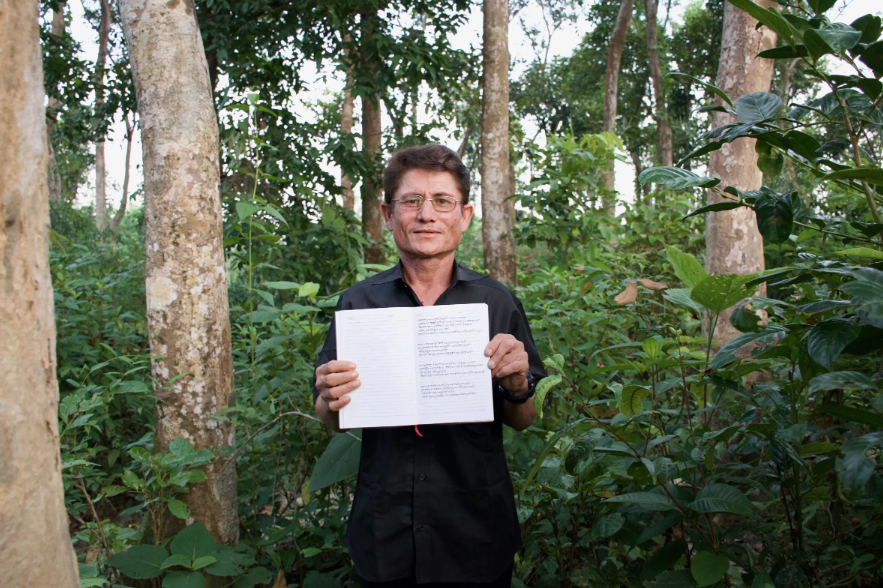

Abdul Mozid carries a notebook filled with songs, his verses written neatly with a fine-tipped pen.

He never went to school, and learned to read and write as an adult. When he was a boy, Mozid says, he had to sell chickens and beg for food.

That’s because his father was one of thousands of Rohingyas in Myanmar who were forced into labor by the government in the 1970s. Mozid was about ten years old then. His father’s absence left no adults around to maintain the family’s clothing shop, so it closed down.

“We survived on hardships,” Mozid says.

One day, his father was attacked while working for the government. It’s unclear who attacked him or what injuries he suffered. But Mozid says the wounds contributed to his death years later, after they reached Bangladesh as refugees.

It was 1992, and the government of Bangladesh had signed an agreement with Myanmar to repatriate Rohingya refugees who had fled forced labor and other atrocities, including sexual assault and extrajudicial killing. The pact meant that thousands of Rohingyas at the border with Bangladesh were turned away, and thousands of people living in Bangladesh’s refugee camps were sent back to Myanmar against their will.

In protest of repatriation, Mozid’s father went on a hunger strike in his refugee camp. After several days of not eating, Mozid watched his father grow weak and die.

“I have this sad feeling inside because my father had to die for this oppression,” Mozid says.

Today he makes “true music,” songs that allow him to express his sorrows: over not having a homeland, Rohingya women who were raped by security forces, and other topics.

Mozid began to make music after an organization inside his refugee camp hosted a competition. “Sometimes when I’m in the mood, I get vibes to write. Maybe at night, if it’s quiet, I get the feeling.”

Because Rohingya kids were often bullied in Rakhine state, along the western coast of Myanmar, Mozid never went to school. He learned to read and write in Bangladesh with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees.

And among his most prized songs is one he wrote about his father. It’s not something he sings publicly — the one time Mozid sang it to a big crowd, he says he made a lot of mistakes. Mozid vows to never perform it again until the song is just right.