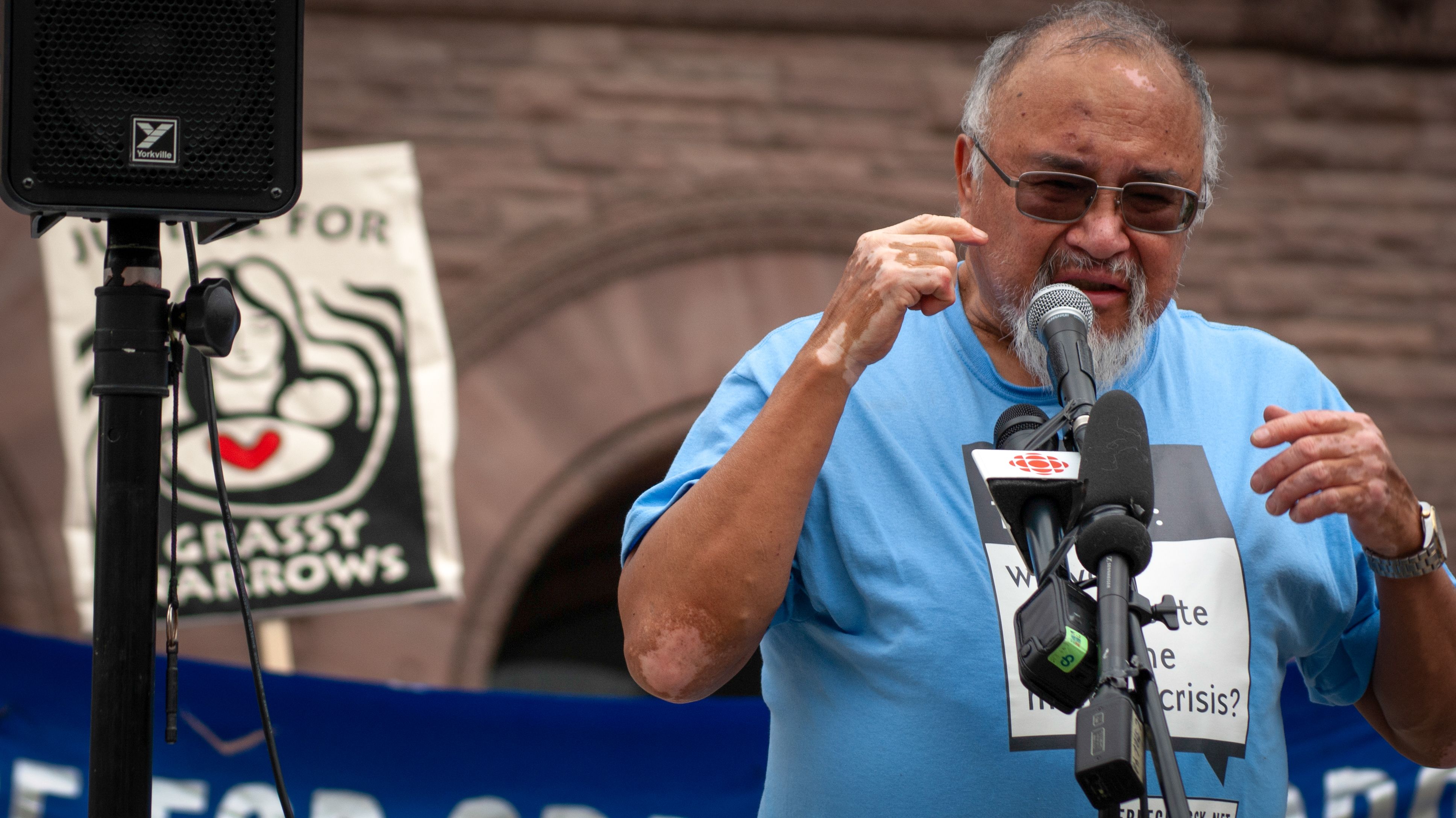

“The pulp and paper mill in Dryden, Ontario, spilled mercury poisoning into our river system and that’s why my ears keep ringing all the time and it makes me sad. It makes me sad. My ears keep ringing all the time; it really makes me sad,” said Grassy Narrows elder Raphael Fobister at a march in Toronto. Together, community members from Grassy Narrows and their supporters marched from Queen’s Park, the home of the Ontario Legislative Building, to the Indigenous Services Office to bring awareness to their cause. With tears in his eyes, Fobister told the crowd of the impact that mercury poisoning has had, and continues to have, on members of his community.

Grassy Narrows First Nation, or the Asubpeeschoseewagong First Nation, is a small First Nations community in northwestern Ontario. For almost 50 years, the river system—a foundational element of the Grassy Narrows culture—-that the community relies on for food and water has been contaminated with mercury as a result of industrial pollution. Today, almost 90 percent of Grassy Narrows community members suffer from symptoms of mercury poisoning.

In the 1960s, the Dryden Chemical Company used mercury in a process to create the materials needed to bleach paper at a paper mill along the English-Wabigoon River, just 320 kilometers upstream from Grassy Narrows. When the company was finished with the mercury cells, it would dump them into the river. Dryden Chemical Company dumped about 10 tonnes of mercury into the river between 1962 and 1970. In recent years, it has been uncovered that the company also buried drums of mercury underground, poisoning the groundwater in the area as well.

“It poisoned our people, and still, today, years later it’s still leaking into the river system that the river people have lived along—you know, hunt and fish everyday. It’s contaminated my children and probably their children too as well unless something is done,” said Jason Kejick, a Grassy Narrows community member, during an interview prior to his community’s march through Toronto.

According to a fact sheet released by the community, local fish caught in the 1970s were determined to contain dangerous levels of mercury. The Canadian government shut down those local fisheries. Then, the community began to notice the effects of mercury poisoning.

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency, neurological symptoms of mercury poisoning include ataxia (a degenerative disease of the nervous system), numbness in the hands and feet, general muscle weakness, and damage to hearing and speech. Continued exposure to mercury can lead to permanent brain and kidney damage and, often, early death. Grassy Narrows and its community members are no stranger to loss.

“Today, in 2019, the life expectancy of our people is low,” said Chrissy Isaacs, a Grassy Narrows community member and proud activist, in an interview following her community’s march through Toronto.

The results of a government-funded study released in 2018 show that, compared to other First Nations communities, Grassy Narrows has significantly fewer elders. According to a summary of the report, the lack of elders in Grassy Narrows is representative of lower life expectancy and has potential to lead to a loss of traditional values.

In addition to the effects on the health of the people, the mercury in their water system has all but eliminated Grassy Narrows ability to financially sustain itself. Besides using the fish found in the water for sustenance for the community, the fish also provided life to both booming tourism and fishing industries. When the poisoning was discovered, both industries declined.

“Our livelihood was taken away. One of the main things that our people did, had to do with the river and that was taken away from our people,” Isaacs said. “We need clean water. We need to be able to sustain ourselves again.”

Grassy Narrow’s fight for clean water began almost immediately after the discovery of mercury in the water. For almost 50 years, the people of Grassy Narrows have fought to make the government aware of their crisis. In addition to protesting their government, the community turned to more traditional means as well.

“I am a believer of honesty and I believe in praying. I do my prayers everyday. And I do my prayers for my people. And I do my prayers for the water in Grassy Narrows,” said Gloria Fobister, a Grassy Narrows elder and first cousin of Steve Fobister, one of the leading voices in Grassy Narrows fight for justice, who passed away in 2018.

The relationship between Canada and the people of the First Nations has always been touched by conflict. More than 10,000 years ago, the first conflict with the government of Canada began shortly after colonization. Besides taking Indigenous land, colonizers also worked to develop programs of assimilation meant to erase the culture of the First Nations.

The most widely known of these programs was the formation of a federal residential school system. Meant as a means of assimilation, residential schools separated Indigenous children from their communities and culture. A number of schools instituted abusive policies to fulfill their goals.

In addition to the residential schools, the First Nations communities were also faced with a practice referred to as the ‘60s Scoop.’ During the 1960s, children were “scooped up” from their communities and then taken to foster homes or put up for adoption. According to Chief Turtle, prior to the mercury poisoning, the people of Grassy Narrows faced both of these policies.

“We’ve been hit with a lot of things. We’ve been hit with mercury, we’ve been hit with residential school, we’ve been hit with the reservation system, we’ve been hit with relocation. All these things have hit my community,” said Grassy Narrows Chief Rudy Turtle, describing his community’s historical relationship with Canada.

Though the Canadian government’s policies on Indigenous people have been abusive historically, the resilience and fight of Grassy Narrows seemingly won out. After years of fighting to be heard, in December 2017, then-Indigenous Services Minister Jane Philpott promised the community that the federal government would pay for the construction and operation of a treatment center in Grassy Narrows. In addition to this promise of federal support, the provincial government of Ontario secured an $85 million trust to aid in the cleanup of the land and water.

Since that time, little has come of either of these promises.

The following January, Philpott was removed from her position as Indigenous Services Minister and was replaced by Seamus O’Regan. Since taking the position, O’Regan has visited the community once. In May 2019, O’Regan visited Grassy Narrows to sign an agreement on the construction and operation of a health facility in the community. The agreement proposed by O’Regan was not legally binding and Grassy Narrows community members were dissatisfied with the proposed agreement, finding it to be an unreliable promise.

Thus, it was not signed.

According to Chief Turtle, the government official that the community most wants the eyes and ears of is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. The community has invited him to visit their land and speak with community members many times, but the invitation has never been accepted. It’s become a source of great frustration for Chief Rudy Turtle and his community.

“The one thing we’ve been asking the Prime Minister to [do, is] come to our community and I keep mentioning that over and over again and I was very disappointed. His excuse is always that, ‘My schedule is very tight. I can’t put you in my schedule.’ And yet, when the Toronto Raptors win a championship he can change his schedule and go sit with all those people and yet he can't sit and put his foot down in Grassy Narrows. It shows where his priorities are,” said Chief Turtle.

Now, more than ever, the attention of Trudeau and his government is crucial. Canada’s federal elections must occur on or before October 21, 2019.

It was while the Liberal Party of Canada was in power that these promises were made to the Grassy Narrows community. If Trudeau’s Liberal Party loses their parliamentary majority, a new government will be formed.

The promise that Trudeau’s government gave to Grassy Narrows, the money required for the building and upkeep of a mercury care home in the community, could mean nothing to a new government and the money could be reallocated. Fearing this outcome, the people of Grassy Narrows are asking the government to put the money they were promised in a trust to ensure that it remains theirs.

“This government said that they were going to give us this mercury home and now that a new election is coming up, there hasn't been anything to even begin building the home,” Chrissy said.

Still the community fights.

“No matter what they hit us with, we always come back up again,” Chief Turtle ensures the crowd in Toronto. “And, no matter what they hit us with in the future, we will come back up again. We are not going away.”