The first time I went to the Agbogblushie Market area of Accra, the taxi driver did two things. He started by charging me three times the real price. Ghana had been my home for nearly two years at that point (this was last September), but I had spent most of my time living cheaply as a Peace Corps Volunteer in the rural north, with little exposure to the comparatively bustling and expensive capital city. I hardly knew where Agbogblushie was, let alone how much the cab fare should be. After a few weak attempts at bargaining, I agreed to the price and got in the car.

The driver's next move, on the ride over, was to warn me that I shouldn't be going to Agbogblushie at all. "It's a bad place," he said. "All the women are prostitutes, and all the men are thieves." He seemed genuinely worried about my safety, and uncomfortable at the thought of having to drive into the place himself. He referred to it as Sodomandgomorrah, which I didn't quite catch at first - in fact, it took me a few days of hearing what I thought was an African word before I realized people were saying Sodom and Gomorrah. Infamous for its supposed sins, the sprawling shantytown around Agbogblushie has been nicknamed after the fabled cities that, according to both the Bible and the Koran, God destroyed after warning the inhabitants to give up their wicked ways.

The driver slowed to a stop on the main road. I paid him and got out. It was getting dark and people were everywhere, but I didn't see the people who had agreed to meet me. I was nervous.

I've learned a few things since that first trip. A taxi ride across town should cost three cedis, not ten; some taxi drivers have an interesting definition of the word "thief"; and, finally, while it may be the nature of myths to have some truth to them, it is unwise to rely on them completely if one wants to get to know a place, or its people.

The people of Sodomandgomorrah (that's how it's spoken, so I'll continue to spell it as such) are predominantly from Ghana's north, that is, the Northern Region, Upper West Region, and Upper East Region - people of the Dagomba, Dagaati, Gonja, Sisali, Konkomba, Mamprusi, and Kusasi tribes, to name just a few. They come south for many reasons, but the root cause is always the same: to escape the barren upper-third of the country and a life of unemployment and meager subsistence farming. Most of them work as laborers in some capacity – young men roam the streets of Accra foraging for scrap metal to sell, while women and girls carry heavy loads of goods on their heads across the city's markets. These porters, or Kayayo as they are called, make up the bulk of the workforce inhabiting Sodomandgomorrah. I won't deny that crime and vice are present there, but I would argue that, contrary to what outsiders believe, most of the people inside are merely trying to make a living, and in some cases a home.

I learned a lot during my time as a Peace Corps Volunteer in a northern village, called Wantugu. Looking back, two things seem most important. I think I "knew" both of them beforehand, but it took the intimacy of living in that setting to truly "learn" them.

The first is that poverty is like a whirlpool, one that is multifaceted and nearly impossible to swim out of. Poor infrastructure and education, lack of access to health care, a harsh climate, long-standing cultural traditions, governmental indifference – all of these factors link together to create a situation from which few can escape, and those who try face a long and difficult road.

For example - there are schools in Wantugu. About half of the teachers were from Tamale, the nearest city, and were expected to commute, or to stay in Wantugu during the week and return to their families on the weekend. However, they were underpaid, their accommodations were minimal, and the road from the city is unpaved and, in some places, can hardly be considered a road. On top of that, there is only a brief rainy season during which northern villagers can farm, providing their food supply and income for the entire year. Once the rains begin to fall, the classrooms clear out, as most of the children are too busy helping their families on the farm. The teachers assigned to Wantugu's schools arrived dedicated; then they started appearing only a day or two each week; finally, they disappeared completely. A good education can lead to a decent job in the city, and allow a person to climb up a rung on the income ladder, but the internal and external factors of poverty deny most of Wantugu's would-be students that chance.

The second thing I've taken away from my experiences is much more heartening – it's a belief that the ways we measure "development" are often inaccurate. People here may live shorter lives and own fewer material goods, but as a whole, my friends in the village seemed to smile more than the average American, and to worry less. While it's common for people in Ghana to ask me to bring them back to the United States, they often change their mind when we get to the details. Once, a man asked me the price of a house in the states, and his eyes widened when I answered. "I'd rather be here," he said. "Here, when I want to build a house, I dig up the earth. When I want water, I walk to the dam. It's much easier."

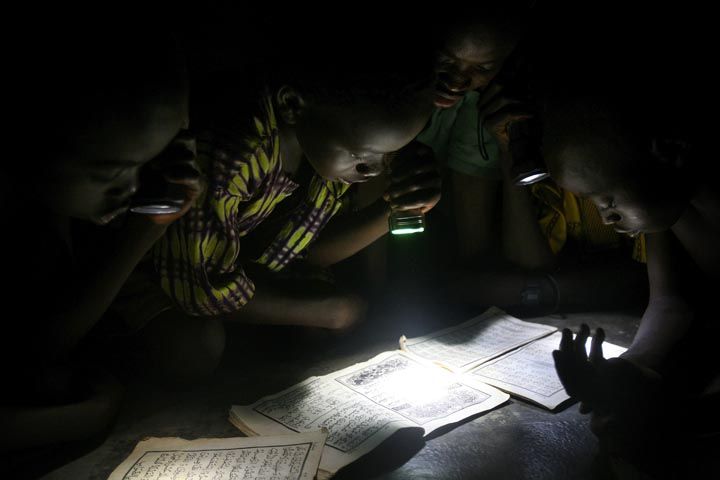

Telling the story of the Kayayo women and girls seemed to be the best way to summarize my experiences in Ghana for an audience. Their place is held fast at the center of poverty's whirlpool. In the north, girls begin working at a young age, cleaning the family compound, fetching water from the dam, and looking after younger siblings. Accurate statistics are hard to come by, but poking your head in any classroom will reveal far more male students than female, especially at higher levels of education. Many feel that Kayayo is their only available option, but their situation improves only marginally, if at all. In Sodomandgomorrah, ten or twenty of them crowd into small rooms to sleep at night, while a young man next-door may enjoy the same size room for himself. They work laboriously for long hours, and make only a few dollars a day, part of which is immediately spent on food and shelter.

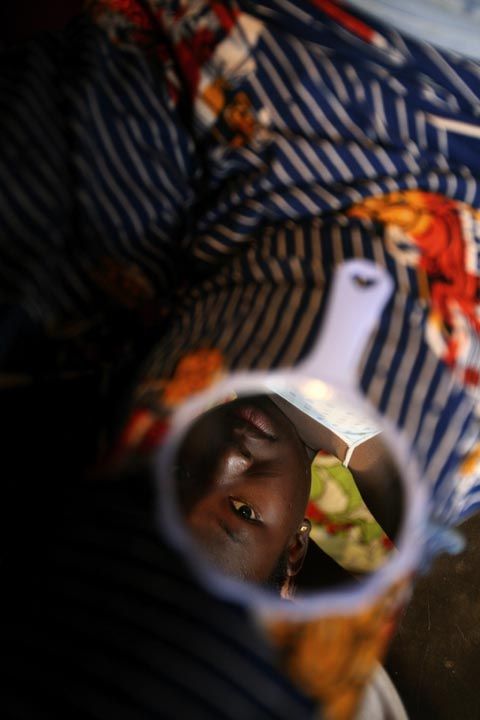

And yet, many seem to relish their new-found freedom. Sodomandgomorrah is a lively place, and the girls' rooms are often filled with laughter. On Sundays, the market doesn't open, and they have the day off to relax with their friends. Those who I've spoken to so far say that they miss their families, but prefer living in the city – they have work there, they say, and opportunities. Some plan to make the little money they can and then return home, to marry or attend school, whereas others have ill-defined plans of staying on in the city and carving out a permanent existence.

In the coming weeks, I will invite some of the Kayayo to tell their stories, finding out their individual reasons for leaving home as well as their future hopes and plans. I will also travel to northern Ghana, and meet with girls who have worked as Kayayo but, in the end, decided to return home. Through this project, I hope to illuminate some of poverty's causes and effects, and to finally put a satisfactory close on a personal chapter in my own life.