PROLOGUE: 'Fighting for Freedom'

For the full interactive experience, visit the Al Jazeera website.

Blue River, BC - As the sun sinks lower on the horizon, Mayuk Manuel rolls a warped tree stump off the road, opening a path that leads to a cluster of tiny houses nestled amid a grove of tall conifers.

The stump and a barrier of plastic orange fencing control entry to the Tiny House Warriors encampment in the community of Blue River, British Columbia (BC). On one of the homes, painted all black with white and red accents, a figure thrusts a spear into the air. On another, a swan spreads its wings next to a majestic mountain range. Signs posted nearby read: "RCMP have no jurisdiction" and "No mountain pipelines".

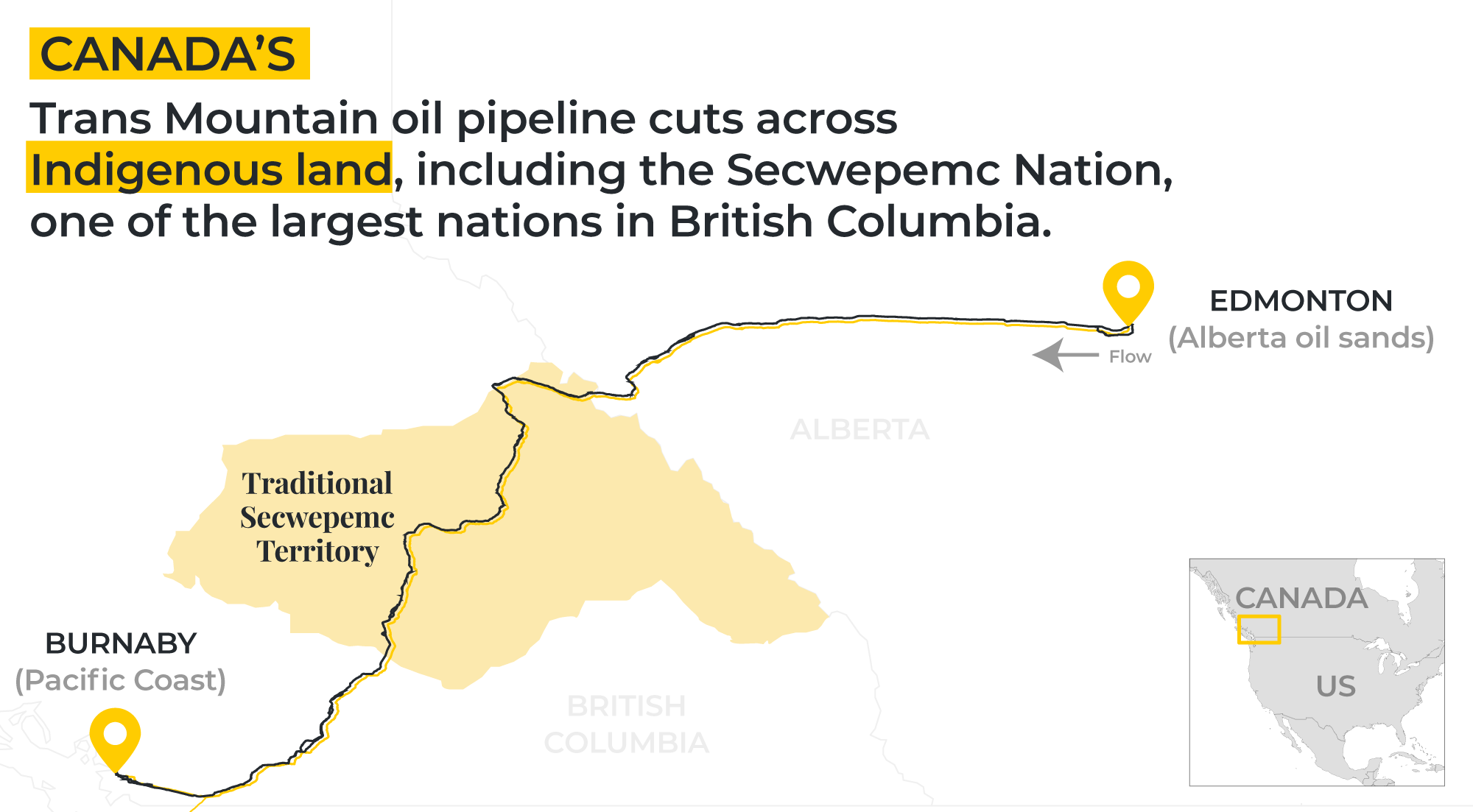

Mayuk and her sister, Kanahus Manuel, are fighting the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion, a $5.6bn ($7.4 billion Canadian) megaproject that would see hundreds of thousands of oil barrels shipped daily from the Canadian province of Alberta to the BC coast, traversing territories that have historically belonged to the Secwepemc peoples in the process.

The pipeline expansion has become a flashpoint for a confluence of issues ranging from climate change and Indigenous rights to economic development, territorial land claims and good governance. Whether it will ultimately be completed remains a question.

"We resisted," Mayuk tells Al Jazeera, standing between the tiny homes as the temperature begins to dip.

"We resisted colonisation since the settlers invaded our land, and we're still resisting, and we're not going to give up," she says. "We're not only fighting for our freedom; we're fighting for freedom of all Indigenous peoples."

"We resisted colonisation since the settlers invaded our land, and we're still resisting, and we're not going to give up." - Mayuk Manuel

The tiny homes at the Blue River encampment are on wheels, designed to be driven to areas along the pipeline path to block construction. One structure was moved in October to a new site near Moonbeam Creek, about 60km (37 miles) north of Blue River.

Inside, the structures are equipped with small wood-burning stoves, mattresses, and clothes, blankets and other personal items. The camp has a makeshift kitchen and a trailer that serves as an electricity hub, powering the other tiny homes.

For Mayuk and Kanahus, the Blue River camp is the epicentre of their struggle to protect their traditional Secwepemc territories, which cover approximately 180,000 square kilometres (69,498sq miles) of the BC interior. They have been detained on multiple occasions for their attempts to protest construction activities on this land.

Kanahus was recently stopped by police on the Southern Yellowhead Highway, en route to Blue River to set up a three-day "action camp and bonfire" event expected to draw dozens of activists to the remote site. She was held for a few hours and handed a police document accusing her of intimidation and theft - charges she vehemently denies - and barring her from going within 30 metres of any Trans Mountain facilities.

She has been detained again since then and knows it will likely happen again. "They know that we are causing a lot of risk and uncertainty around economics, and their business ventures here in Canada," she says, adding that the battle will continue regardless.

"We're standing on hard law," Kanahus says. "We're standing on title."

CHAPTER I: Buying a Pipeline

Edmonton, AB - To fully understand the genesis of this small encampment near the Alberta-BC border, it is necessary to travel about 600km (373 miles) northeast to the city of Edmonton, where the Trans Mountain oil pipeline begins.

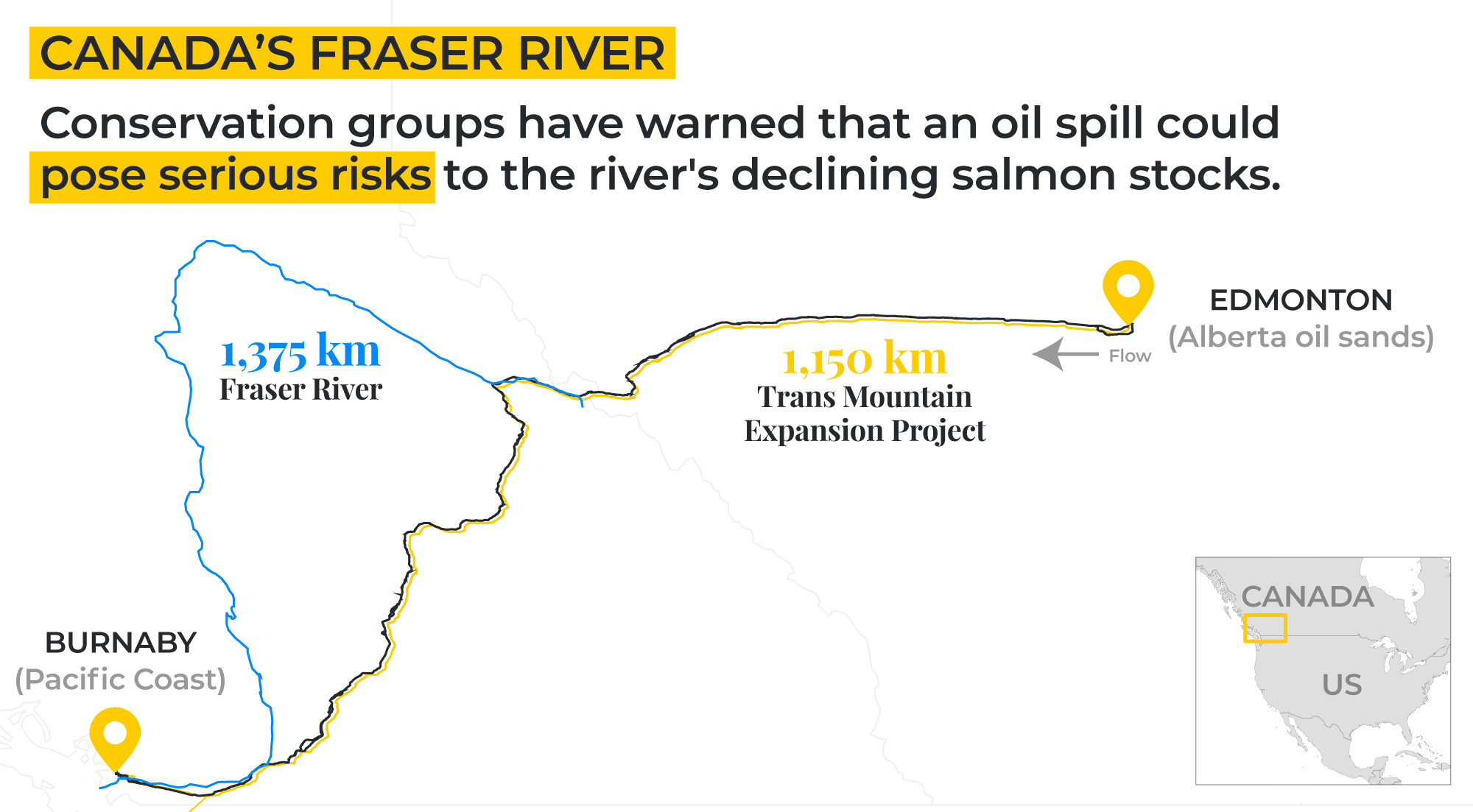

The original pipeline has been in operation since 1953. It carries about 300,000 barrels of oil a day from Alberta's tar sands down a 1,150km (715-mile) route to Canada's west coast for export overseas. The expansion would see a twinned pipeline snake down the same route, nearly tripling the system's capacity to 890,000 barrels a day. A new phase of construction on the second pipeline started on Tuesday.

The pipeline has divided dozens of Indigenous communities whose traditional territory runs along its path and spurred pushback from environmentalists, who point to the risks of a spill on critical waterways and wildlife. This includes Jasper National Park, whose ecosystems the Canadian government acknowledges are "especially fragile", and the Fraser River, whose salmon stocks are already in decline. Since the existing pipeline began operations more than six decades ago, the company has reported about 84 spills.

The expansion was contentious from the start, with protests and legal challenges mounting against the megaproject for years. Despite the opposition, in May 2018, the Canadian government announced plans to purchase the pipeline for $3.4bn ($4.5 billion Canadian) from Kinder Morgan Canada Limited, the Canadian subsidiary of Texas-based oil giant Kinder Morgan.

"Make no mistake," Finance Minister Bill Morneau said at the time, "this is an investment in Canada's future."

Although the pipeline fuelled controversy during Canada's recent election campaign, with the Green and New Democratic parties pushing to cancel the expansion, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau - whose majority Liberal government was reduced to a minority in the October vote - insists the project will move ahead.

"Albertans and people in Saskatchewan have faced very difficult years … because of the global commodity prices, because of the challenges they are facing," Trudeau told a news conference two days after the vote. "For a long time, they weren't able to get their resources to markets other than the United States. We are moving forward to solve those challenges."

On Tuesday, Trans Mountain and the federal government hailed the start of construction on a 50-km (31-mile) section of the twinned pipeline that runs from the Edmonton terminal west to Acheson, Alberta.

"Getting shovels in the ground in Alberta and kicking off pipeline construction is a pivotal moment for Trans Mountain," said Trans Mountain President and CEO Ian Anderson in a statement.

"It's a good day for Canada," added Seamus O'Regan, the Canadian minister of natural resources, who said the expansion project "is supporting workers and will keep our energy sector strong".

How long the government of Canada will retain ownership of the pipeline, however, remains an open question. Dozens of Indigenous groups along the pipeline route have reached "mutual benefit agreements" with Trans Mountain, a federal Crown corporation, to pave the way for construction - and some are looking for an ownership stake. The government says it is currently undertaking an engagement process with Indigenous groups to explore such possibilities, which could include an outright sale.

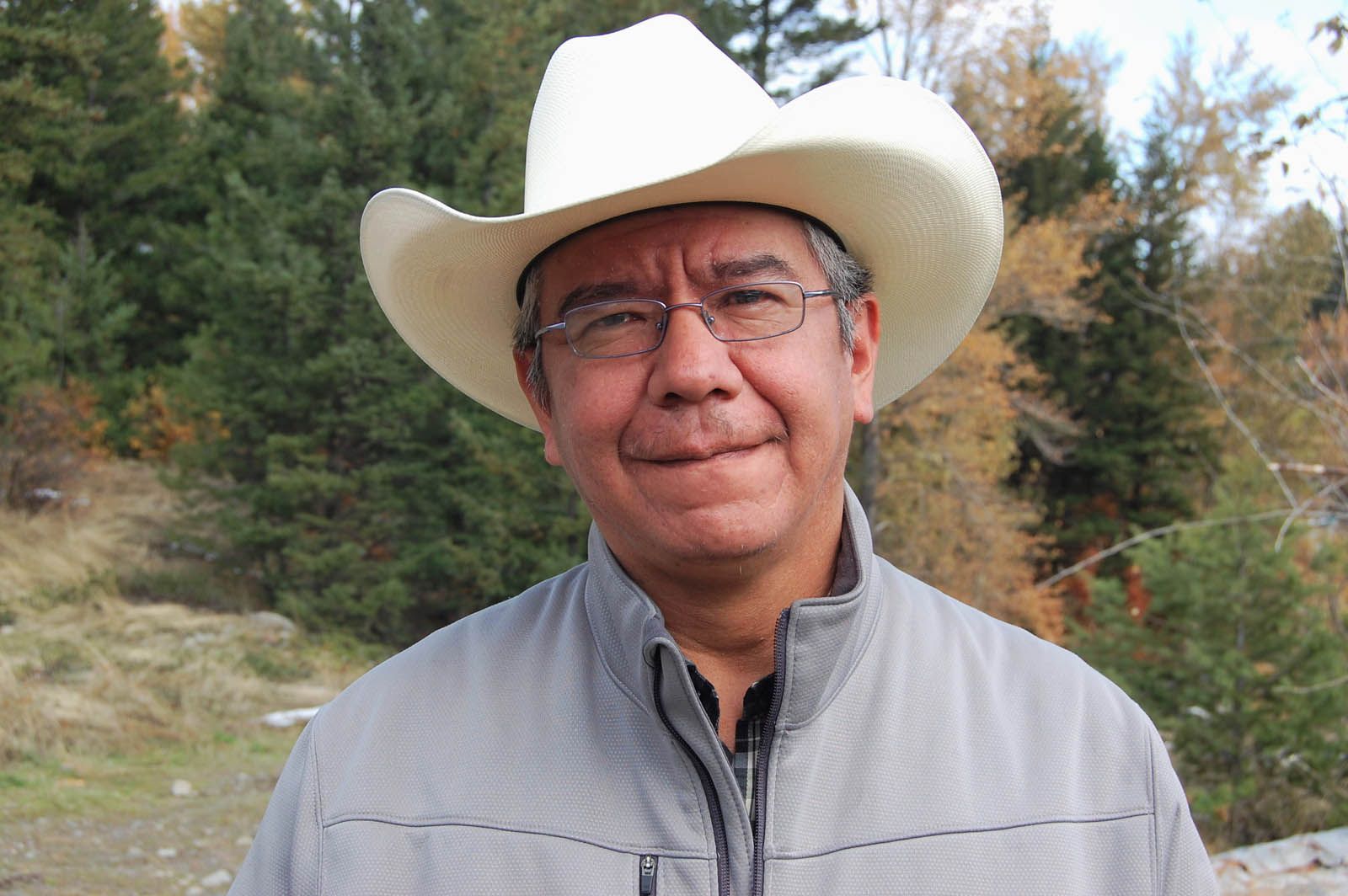

Chief Mike LeBourdais, leader of the Western Indigenous Pipeline Group, a collection of Indigenous leaders along the pipeline path, says he believes all it would take for his group to acquire the Trans Mountain project is "a big fat cheque".

Wearing a white cowboy hat and jeans, LeBourdais speaks intensely - quick, defensive, and not mincing words - as he outlines his group's bid, suggesting they could obtain the requisite billions of dollars by presenting a strong case to the bank.

"Everything's for sale ... The pipeline's going to get sold, and if they don't sell it to the First Nations, they're going to piss off all the First Nations, and so we think we're uniquely structured," he tells Al Jazeera, noting that such a purchase would be a "game-changer" for Indigenous communities.

"Everything's for sale ... The pipeline's going to get sold." - Chief Mike LeBourdais

"You get revenue and environmental oversight, two things we don't have now," LeBourdais says.

Considering the vehement opposition to the project in some Indigenous communities, LeBourdais says he would plan to adjust the pipeline route to avoid those areas, which could result in a more circuitous - and more expensive - path. "If they don't like it, fine, let's go somewhere else," he says. "It's a pipe, it's not a cathedral ... If I owned it, I would move it. It's that simple."

Stephen Buffalo, the president and CEO of the Indian Resource Council, which advocates for dozens of oil- and gas-producing First Nations across Canada, says the pipeline expansion would provide a crucial source of revenue for cash-strapped communities. Federal money received under the Indian Act, the statute that lays out government control over Indigenous communities, is "simply not enough", Buffalo tells Al Jazeera.

At the end of the day, he says, "this is our land, and we want to not only protect it, but we want to benefit from it ourselves, and we want to provide something safe for future generations - but the only way we can do that is if we're part of the ownership, if we're part of the talks, we're part of the decisions that are made.

"When we fight against each other, we're going to be losing the battle."

A strong majority of Albertans support Trans Mountain, and members of various First Nations in the province have come out in favour of the expansion project. Paul First Nation signed an agreement with Kinder Morgan back in 2014, just months after the company filed an application for permission to build with the National Energy Board, an independent agency tasked with regulating major resource projects in Canada. Last year, Enoch Cree Nation Chief Billy Morin said Indigenous groups should seize the economic opportunities generated by the pipeline. And Chief Tony Alexis, who leads the Alexis Nakota Sioux Nation, heads another group, the Iron Coalition, that is aiming to purchase it.

None of these three western Alberta First Nations granted Al Jazeera's repeated requests for interviews. Other Indigenous groups whose leaders have expressed support or reached agreements with Trans Mountain, including the Metis Nation British Columbia, the Metis Nation of Alberta, Simpcw First Nation and Yale First Nation, also declined to be interviewed or did not respond to repeated requests.

"When I signed this deal, I felt a lot of shame," Yale First Nation Chief Ken Hansen told APTN News last year, noting that his band only signed a deal with Trans Mountain because it had no other financial options.

Edson, AB - About 150km (93 miles) west of Paul First Nation, in Edson, Alberta, rows of pipeline segments are already stacked, three pipes high, in a massive site just off the Yellowhead Highway. Cars and trucks whiz by the stockpile, which sits behind a fence equipped with surveillance cameras. Billboards for roadside hotels and restaurants dot this stretch of highway near the town of about 8,000 people.

Valerie Findlay, who is Metis and the director of the Edson Friendship Centre, says the pipeline expansion "hasn't caused controversy, because of a lot of the businesses … rely on it''. Still, she says she is concerned about the potential risks of the expansion project. "If there's a break in the pipeline, it does damage our land, and our soil, and our waterways … There is a huge risk by putting the pipeline in."

There is a huge risk by putting the pipeline in." - Valerie Findlay

CHAPTER II: Who Owns the Land?

Vancouver, BC - As the existing pipeline weaves its way from Alberta through BC, perceptions of the expansion project's benefits - and costs - shift dramatically.

On the fourth floor of a bright, shared office building in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside, a red stop sign greets visitors to the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs (UBCIC), a group that works for the recognition of Aboriginal title and rights in the province.

"Stop Kinder Morgan Pipeline," the sign reads. Stretched across a wall inside the lobby is a black-and-white group photo of Indigenous chiefs from a landmark meeting in 1969, the year UBCIC was founded.

The organisation has been vocal in its opposition to the Trans Mountain project, as many Indigenous leaders in BC say the Canadian government never got "free, prior and informed consent" from the communities that would be affected by the expansion.

That doctrine is contained in the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), which outlines the rights and protections of Indigenous peoples around the world. Canada, which first voted against UNDRIP in 2007, has since signed on, but the document is not part of Canadian law. In late November, BC became the first province in Canada to formally implement UNDRIP, unanimously passing a law that forces the province to make sure its policies are in line with the UN declaration.

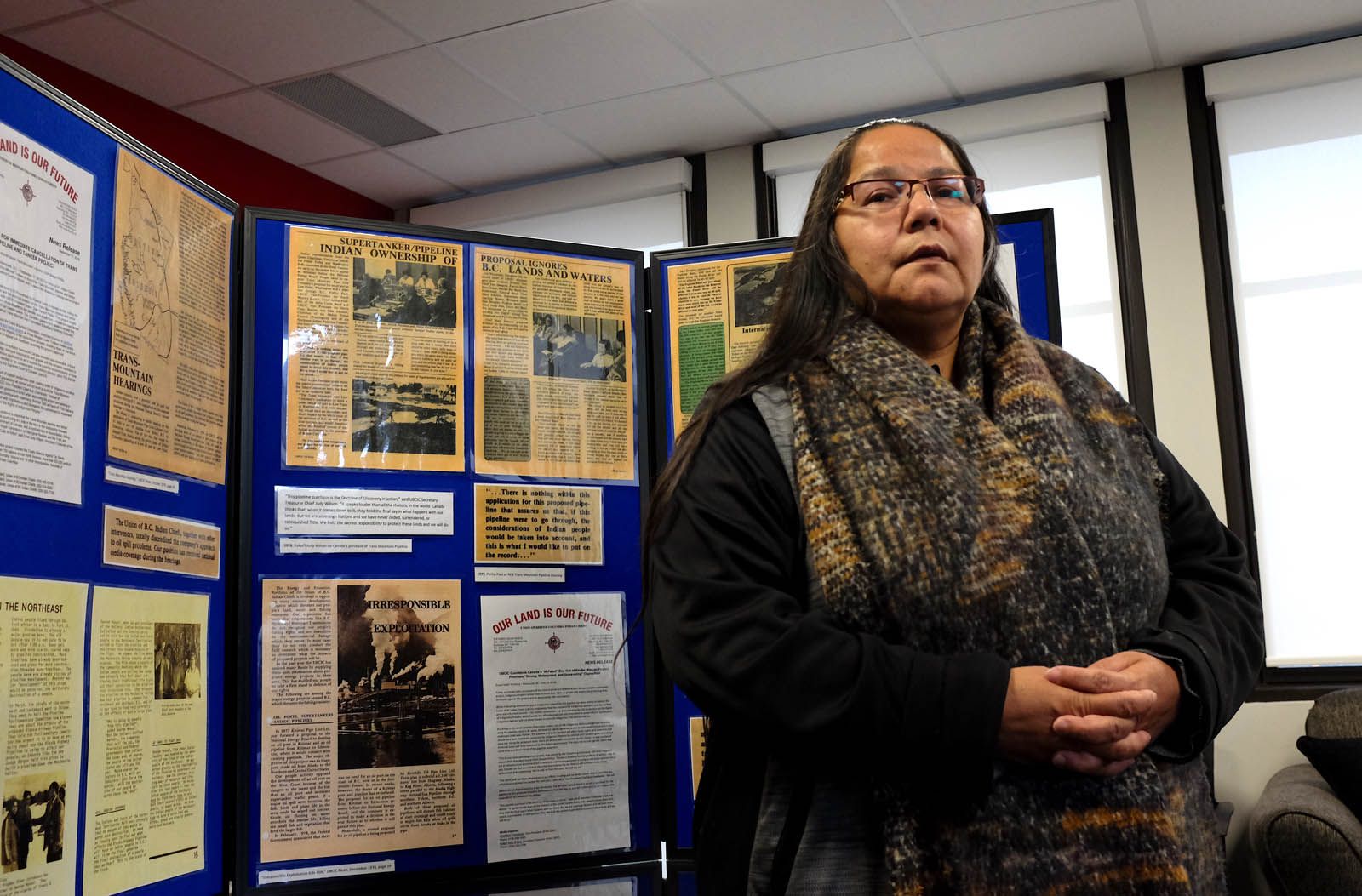

Judy Wilson, chief of the Neskonlith Indian Band and UBCIC secretary-treasurer, says that getting an OK for the pipeline from band councils and chiefs on reserves is not what really matters. Instead, the real question is: Who holds the underlying title to the territory?

"In our nation, Secwepemc, it's collectively the people that hold proper title," she says. "And they haven't transferred their consent or their authority to any chief and council or anybody to say they can sign a document on their behalf or sign away their rights or sign away their consent."

"In our nation, Secwepemc, it's collectively the people that hold proper title." - Chief Judy Wilson

In Canada, the term "Aboriginal title" refers to Indigenous peoples' inherent right to the use of and control over their traditional territories, a concept that has been recognised by the Supreme Court of Canada and by the United Nations. The way Aboriginal title is held varies depending on the nation. "Aboriginal title arises out of prior occupation of the land by aboriginal peoples," the Supreme Court said in a 1997 ruling. But the government has taken what some experts describe as a "prove it" approach to Aboriginal title, forcing nations to prove their title exists in order for it to be applied.

Yet, more than a century ago, Canada set up what are called First Nations reserves in which to concentrate Indigenous peoples in Canada. Members of Indian bands can live on reserves, and the elected bodies that make decisions on those reserves - known as band councils - were also set up by the government under the Indian Act, which was first passed in the late 1800s and has been amended several times since. The reserves were created in places that often did not match an Indigenous nation's traditional lands and, in BC, reserve land accounts for just 0.4 percent of the provincial land base. Reserve land is owned by the government.

The band council system has been described as one that sought to erase Indigenous peoples' traditional systems of self-governance. "For over a century, Canadian policies have eroded the traditional political systems of Aboriginal peoples, and imposed a governance system - band council and elections - disconnected from, and alien to, their cultures," a 2010 report from the Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples said.

Moreover, most of the land in BC is unceded, meaning that Indigenous nations have not surrendered the title to their territories, nor have those territories been acquired by the government. A government-brokered treaty negotiation process to address the issue, and grant Indigenous peoples ownership and management over their lands, has been under way for decades.

In that context, Wilson says the government must consult the proper titleholders on a project such as Trans Mountain. The Secwepemc Nation asserts Aboriginal title over 180,000 square kilometres (69,498sq miles) in BC, making it "one of the largest nations in the interior" of the province, she says.

"No one's ever come out to talk to our people collectively, the proper titleholders. They have never gotten the consent from our people. They haven't even been adequately informed," Wilson says, standing in front of a poster board covered in newspaper clippings and other documents describing decades of Indigenous opposition to Trans Mountain. When the original Trans Mountain pipeline was built in 1953, Indigenous people could not legally organise around the question of land title and jurisdiction, law professor Nicole Schabus told APTN last year, but subsequent Supreme Court decisions have strengthened those rights.

"They have never gotten the consent from our people." - Chief Judy Wilson

While Indigenous rights are inherent, they were made constitutional in the Constitution Act of 1982, Section 35 of which states that "the existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognised and affirmed". Canadian courts have more closely defined what that means, and several cases have been key in that process, including the Haida Nation v British Columbia decision in 2004, which outlined the Crown's "duty to consult" Indigenous communities on projects that could affect their rights.

"What the court said in Haida is that essentially there's a spectrum," says Eugene Kung, a staff lawyer with West Coast Environmental Law, a legal non-profit in BC. "The more the project or the decision impacts or could impact those [Aboriginal] rights ... the higher the duty to consult."

The duty to consult is also meant to be a temporary protection while the underlying title issues are resolved, Kung says. He points to a 1977 report into a gas pipeline that planned to cut through Canada's northern Mackenzie Valley, known as the Berger Inquiry, which concluded that the project should not go ahead without first settling questions around Aboriginal title.

"The protection and upholding of Aboriginal rights is something that First Nations in Canada take very seriously and that they have the tools to defend through the courts … Continuing a pattern of ignoring that these rights exist and hoping that they go away is not going to get anyone what they want," Kung says.

Both Trans Mountain and Ottawa have conducted separate rounds of consultations with more than 130 Indigenous groups in recent years, a process that has been rejected by some Indigenous leaders as rushed, flawed and merely paying lip-service to the notion of dialogue. A handful of groups are set to go before the Federal Court of Appeal in December to argue that the Crown did not fulfil its duty to consult.

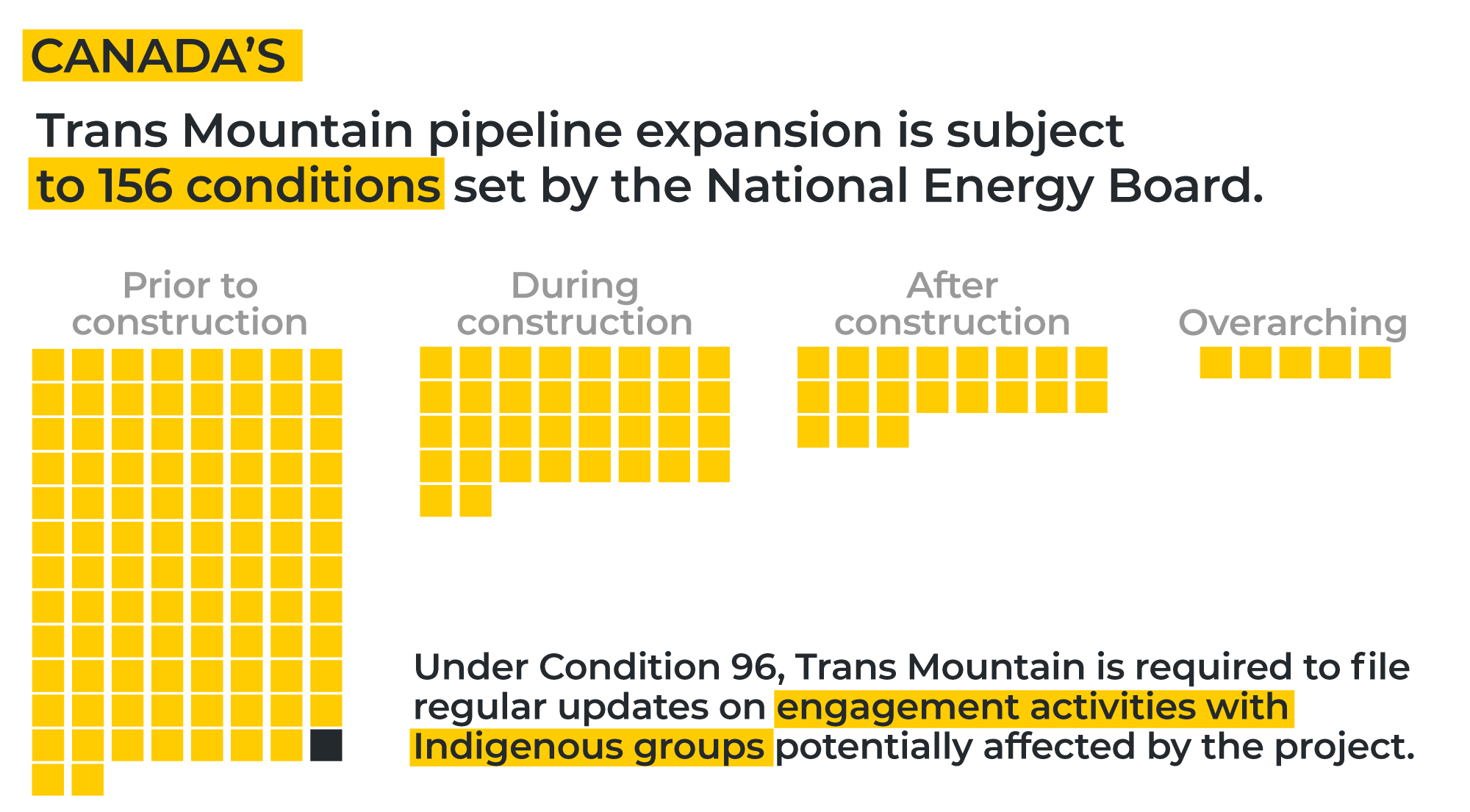

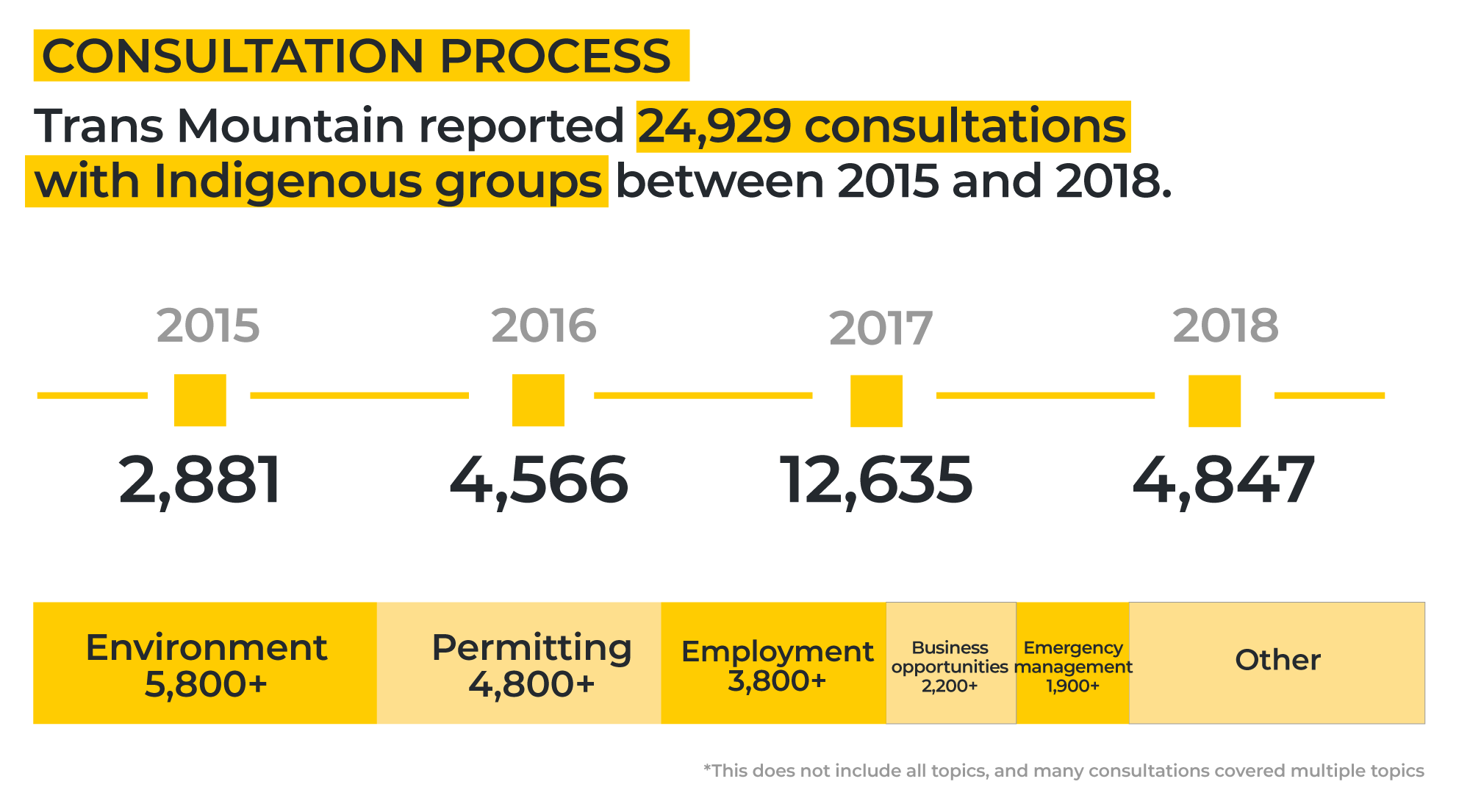

Al Jazeera analysed thousands of pages of consultation data from publicly available filings submitted by Trans Mountain to the National Energy Board, required as part of a set of 156 conditions imposed by the board to allow construction of the pipeline.

Of nearly 25,000 reported consultations spanning the years 2015 to 2018, more than three-quarters - 76 percent - were conducted via email, 16 percent via regular mail, 5 percent via telephone or voicemail, and just 3 percent in person. More than half the consultations were conducted in a single year, 2017, on the heels of the project's initial approval by the federal cabinet. Among the most-discussed topics was the environment.

The separate consultative track led by the federal government determined that the "greatest assessed impact" on each affected Indigenous group would not exceed the level of "moderate" in any instance. The government's report looked at potential effects on hunting, fishing, harvesting, Aboriginal title, cultural practices and other issues, deeming most to be negligible, minor or minor-to-moderate.

This report came after the Federal Court of Appeal in August 2018 determined that a previous round of Crown consultations "did not adequately take into account the concerns of Indigenous groups or explore possible accommodation of those concerns", and directed the government to redo the process. The 2018 ruling overturned the government's approval of the Trans Mountain expansion, but the project was approved again this past June after the renewed round of consultations.

Details of these new federal consultations, however, have not been made publicly available. Natural Resources Canada declined Al Jazeera's request to obtain a copy of the government's consultation log, citing a need to "respect the confidentiality of the consultation process and the nation-to-nation relationship".

Alexandre Deslongchamps, a spokesman for Natural Resources Canada, said in an email to Al Jazeera that the government was confident that it had fulfilled its duty to consult. "As a result of renewed consultations, we committed to implementing eight accommodation measures which address Indigenous concerns on marine safety, protecting the Southern Resident Killer Whale, advancing cumulative effects management and strengthening emergency response," he noted.

But Gordon Christie, a UBC professor with expertise in First Nations law, says that Canada is "still not quite there" in terms of recognising Indigenous authority. "Canada imposed itself upon Indigenous communities over the last several centuries, and those communities were here thousands of years before Canada showed up. And so, they have legal authority over their lands," he says.

UBCIC's Wilson also questions whether the Canadian government can be an honest broker in Trans Mountain consultations. "They're supposed to consult us, but as owners of the pipeline now, [the government] has a conflict of interest because [it] has a vested interest in the pipeline," she says.

"I don't see how the Crown can come out with anything remotely fair."

A short drive southeast of the UBCIC office, Trans Mountain spokeswoman Ali Hounsell speaks to Al Jazeera in the lobby of the corporation's Burnaby office. She expresses confidence that the pipeline expansion is on track.

"We value the Indigenous communities, we deeply respect their rights and title … [and this] is about building trust and respect mutually, over time," Hounsell says. She notes that Trans Mountain has made significant efforts to ensure the pipeline is safe, using advanced technology to detect anomalies in the structure and to prevent spills.

"We value the Indigenous communities, we deeply respect their rights and title … [and this] is about building trust and respect mutually, over time." - Ali Hounsell

"Not everyone will agree with the project … but the bottom line is, we have our approvals, we have the regulatory and the federal government's approval to move forward," Hounsell says. Trans Mountain feels "more certain now than we have in a long time" that the project will reach completion, she adds. "I think that it may look uncertain, but we're building … [It] is moving forward in a way that it hasn't before, and it's got that momentum to it."

CHAPTER III: Court Battles

Merritt, BC - About 250km (155 miles) northeast of Trans Mountain's Burnaby office, a small Indigenous community has found itself at the centre of the fight against the pipeline - and Coldwater Indian Band's legal challenge against Trans Mountain has the potential to stop the project in its tracks.

The two-lane road into Coldwater winds past fenced-in fields where cows and horses graze. When the road straightens out, small houses appear on either side between the trees. After a left turn at the band office and a drive up a short hill, yellow signposts become visible, dotting the community and marking the path of the original Trans Mountain pipeline.

The pipeline has run through Coldwater since the early 1950s, says Chief Lee Spahan, wearing a white cowboy hat and grey pullover adorned with the Coldwater Indian Band crest, as he stands next to one of the yellow markers.

Part of the Nlaka'pamux Nation, Coldwater counts 850 band members, and a vast majority of the people on reserve rely on an underground aquifer to get clean drinking water, Spahan says. The pipeline "poses great risks for the use of that water", he tells Al Jazeera. "It's not if it happens, it's when is it going to happen - because where are we going to get our drinking water if it gets contaminated, when it gets contaminated?"

Spahan says Coldwater members have been trying for years to resolve a dispute over the existing pipeline. In the 1950s, the company that operated the pipeline paid Coldwater $981 ($1,292 Canadian) to build on the reserve, and an additional $855 ($1,125 Canadian) for damages and loss of timber during construction.

A Federal Court of Appeal ruled in 2017 that the terms of compensation had to be renegotiated with Coldwater. But the issue still hasn't been resolved and, without it, Spahan says Coldwater will not enter into any talks over the expansion. A request for a detailed study on the potential effects on the aquifer also remains in the preliminary stages. "We want it done the right way," Spahan says. "It doesn't matter how long it's going to take, because we need to know the risks."

In the face of the opposition from Coldwater, Trans Mountain's Hounsell says that section of the twinned pipeline "goes around" the community. But Spahan says that doesn't solve the problem; a spill outside the boundaries of the reserve could still affect nearby creeks and the community's drinking water. "They're saying, 'We don't need your consent if we go outside the reserve'. But they're still within our traditional, unceded territory and they have to deal with us on that," says Spahan, who describes the consultation process as "flawed right from the beginning".

"If you're going to do it, do it right … make it meaningful. To me, the consultation wasn't meaningful. Absolutely not."

"If you're going to do it, do it right … make it meaningful. To me, the consultation wasn't meaningful. Absolutely not." - Chief Lee Spahan

Canadian courts have backed that position. In its August 2018 decision overturning the government's approval of the expansion, the Federal Court of Appeal wrote that "Canada failed to meaningfully engage with Coldwater, and to discuss and explore options to deal with the real concern about the sole source of drinking water for its Reserve".

In September, the court gave Coldwater and five other Indigenous groups a green light to appeal the government's most recent approval of the project, on the basis that they weren't adequately consulted during the Crown's renewed consultation period, which ran from August 2018 to June 2019. Two Indigenous groups that were involved in the appeal dropped out of the case in November. The Upper Nicola Band, a Syilx community 45km (30 miles) east of Merritt, BC, and Stk'emlupsemc te Secwepemc, based in the area of Kamloops, BC, announced that they had reached an agreement with Trans Mountain on the expansion project.

Upper Nicola Band Chief Harvey McLeod said in a statement that the community got "the best deal possible under the circumstances", but criticised the consultation process. "Canada still has a lot of work to do to recognise and respect Syilx title and rights, including our governance rights, and engage in consent-based dialogue with Upper Nicola and with our Nation," he said.

The appeal is going ahead, however, with the next hearings in the case expected later in December.

"This is one of the smallest reserves, and yet we have to fight for everything that happens here on the reserve, but also within our traditional territory. They need to respect us in our decisions and know who we are and how we are connected to this land," Spahan says.

Abbotsford, BC - That feeling is echoed by Kwilosntun (Murray Ned), a councillor in Sumas First Nation, just off the Trans-Canada Highway near Abbotsford, BC, about 180km (112 miles) southwest of Coldwater.

Part of the larger Sto:Lo Nation, the community sits at the foot of Sumas Mountain, surrounded by trees and several resource-extraction sites. Yellow right-of-way markers line the Sumas First Nation area, warning passersby that the Trans Mountain pipeline runs underground here. A related tank farm - a collection of massive, white oil tanks - also sits on the mountain, behind a fence adorned with warning signs.

Kwilosntun tells Al Jazeera that Sumas community members have long called for accommodation or compensation for the existing Trans Mountain pipeline and the tank farm - but to no avail. "Our individual position is we're not necessarily moving forward until we deal with that - and then consider a secondary line," he says.

He says a few oil breaches have already been recorded in the area, and his biggest concern is the potential environmental consequences of a spill. When the expansion is completed, seven tanks will have a capacity of 890,000 barrels of oil at the Sumas Terminal. "Murphy's Law suggests that if it could happen, it will happen. Even if they put in a new, improved line, at some point there's going to be a breach," Kwilosntun says.

"Even if they put in a new, improved line, at some point there's going to be a breach." - Kwilosntun

The community also has a specific fear that the pipeline may harm cultural sites on Sumas Mountain that hold significance to the entire Sto:Lo Nation. One of those areas is known as Lightning Rock, where tooth-like boulders jut out from the ground under a large tree at the foot of the mountain. Kwilosntun explains how, according to oral histories, a shaman at the site confronted a god-like creature, who turned the shaman into several pieces of stone. The area is also home to a mass burial site that holds cultural importance to the people of Sumas. "If the government is truly interested in reconciliation, then they'll find a way to accommodate our concerns," he says.

Still, some Indigenous proponents of the project insist that people should get on board. By seeking an ownership stake in the Trans Mountain project, they can generate revenue that can go back into Indigenous communities that are struggling, says Delbert Wapass, a former chief of Thunderchild First Nation in Saskatchewan, one province east of Alberta.

Wapass heads Project Reconciliation, a Calgary-based group that wants to purchase an ownership stake in the pipeline. He says it is a matter of putting the decision-making power into the hands of Indigenous peoples so that they can decide for themselves what is best for their communities. "We've been economically starved out as Indigenous peoples from any economic participation in such major projects, and we've always watched from the sideline because we've never been allowed to participate," he tells Al Jazeera in a telephone interview.

"We've been economically starved out as Indigenous peoples from any economic participation." - Delbert Wapass

"So why not? Why not the Trans Mountain pipeline? Why not the LNG project [in northern BC]? Why not all of these other infrastructure opportunities that are out there?"

Earlier this year, the group presented a proposal to the federal government "with the caveat that it was going to be open to be tweaked", and Wapass says Ottawa "was very receptive". He says that, based on recent valuations and analyses of the costs, it would take approximately $5.3bn ($7bn Canadian) to purchase a majority stake in the project. "We have banks that are behind it and supporting it. We're ready to go," he adds.

But back in Sumas, Kwilosntun says he would rather struggle today than saddle future generations with a potentially devastating pipeline spill, whatever amount of money is involved. "Money can't buy us," he says, adding that his community is prepared "to deploy direct action" if necessary to defend their rights.

"Money can't buy us." - Kwilosntun

"We don't want to have to look at this seven generations down the road, where we have made a poor decision that's going to impact some of our members that are not yet born," he says. "Government needs to deal directly with us - with our leadership, with our members, with our elders, our knowledge holders - and free, prior and informed consent comes to mind when we're talking about this whole project … We're obviously not there yet."

CHAPTER IV: Keeping Watch

North Vancouver, BC - About an hour's drive northwest of Sumas, Ta'ah Amy George leans back against the sofa in her North Vancouver living room, the sun beaming through a window that looks out onto the water.

She recounts how she was down by the Salish Sea, which laps up against a rocky shore just a few hundred metres from her home - and everything was black. "The water was black, and there's only three houses standing here, and it was just all dry. There's just no life," says George, an elder of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation, one of many groups of Coast Salish peoples spread out across the Pacific Northwest.

But what she saw wasn't a dream, George says. It was a vision. "I don't know if this was a look into the future if we allow them to go through," she says. "We weren't here any more."

The Tsleil-Waututh have been here - on the banks of the Salish Sea - for thousands of years, and their community holds a sacred trust to act as stewards to protect the land, air and water of their territory. Today, they are fighting to stop the Trans Mountain expansion.

One of their main concerns is the project's effects on marine life. The expansion would lead to an approximate 580-percent increase in tanker traffic in the waters off Burnaby and North Vancouver - a key habitat for southern orca whales and other marine life. That presents too much risk, says George - and it is a risk that she and other members of her nation say they are not willing to take.

"All my ancestors up until this day ... have been stewards of this land and this water," she says, about what motivates her to oppose the project. "We're just picking up what our ancestors have been doing since Contact."

"All my ancestors up until this day ... have been stewards of this land and this water." - Ta'ah Amy George

The Tsleil-Waututh Nation is one of the four Indigenous groups appealing the government's approval of the expansion. It is also applying to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada, arguing that the lower court erred in its decision to restrict the scope of their challenge to the project. In its September ruling, the Federal Court of Appeal limited the case to whether or not the government adequately consulted Indigenous groups, meaning no other issues can be raised.

"We are taking this issue to the Supreme Court of Canada not only to stand up for our inherent and constitutionally protected rights, but also to make sure that Canada follows their own laws when making decisions," Tsleil-Waututh Chief Leah Sisi-ya-ama George-Wilson said in a statement.

Bill Gallagher, an Ontario-based lawyer and resource development strategist, tells Al Jazeera that First Nations have won hundreds of court cases across Canada, and there is a "huge question mark of legal uncertainty over this project [Trans Mountain] at this point in time". The situation, he says, is akin to a "pressure cooker".

"If you don't have Native involvement, and a Native insurance policy for your project, there's a likely chance that it just won't happen - more than 50 percent," Gallagher says.

Indigenous peoples are not the only ones opposed to Trans Mountain, either. Some of the most sustained opposition to the pipeline has been in the Vancouver area, where environmentalists, politicians at the municipal, provincial and federal levels, and residents have stood alongside Indigenous nations to say unequivocally that they will not let the project go forward.

Mike Hudema, a climate campaigner at Greenpeace Canada, says a spill in the water here could do "irreversible" harm to ecosystems and marine life, including the at-risk orca whales, not to mention threaten local communities and thousands of jobs that rely on a clean coastline. The urgent global need to take "action on climate change should make any expansion a non-starter", Hudema tells Al Jazeera in a telephone interview.

"There's no way we should be building a new fossil fuel project to last the next 30 to 40 years when we have to be off fossil fuels in the next 20," he says. "It really is ridiculous from start to finish and it's quite tragic that our government is still trying to pursue this project," he adds, saying that if Ottawa moves ahead with the project, it will continue to "meet with fierce opposition".

Will George of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation is one of those fierce opponents. At the request of an elder in his community, he helped erect a watch house next to Trans Mountain's Burnaby Terminal, the pipeline's endpoint, which the company plans to expand to eventually hold 26 oil tanks. A watch house "was a tool we used centuries ago", he explains in an interview in Vancouver. "A lot of other cultures use it as well; a place to look from and to monitor and see if the enemy is coming.

"We honour our ancestors by protecting that water."

A simple wooden structure with a ramp leading up to the front door, the watch house stands in a small clearing on the edges of a thick forest of pine and other trees. "Kwekwecnewtxw [meaning 'a place to watch from'] Protect the Inlet," reads a banner strung up at the site.

Like the Tiny House Warriors back in Blue River, James McNeil Leyden, an activist who sometimes monitors the house, says it is about more than just blocking a pipeline. "We're protecting the mountains, we're protecting the Salish Sea, we're protecting everyone around here." But he says the watch house will be there however long it takes to stop Trans Mountain from moving ahead with its plans. "It's going to be over our dead bodies that it happens. So this is here for the long run," he says.

Once the expansion is completed, the company says another end-point terminal in Burnaby, known as the Westridge Marine Terminal, will be able to load about 34 tankers a month to take the oil to foreign markets - up from five tankers currently. Massive, green oil tanks currently sit on the edge of the water, just metres from several homes, a walking path and a busy thoroughfare. "Any person who obstructs access to this site ... may be subject to immediate arrest and prosecution," reads a sign on the gate.

Numerous protests have been organised outside the terminal, and activists have been arrested several times at the site. Will George says that's a fight that will continue, despite what sometimes feels like insurmountable odds.

"It's absolutely terrifying. It keeps me up late at night, doing what I do ... but what keeps me going is my son, my nieces and nephews, my old ones, my loved ones," he says. "We're running out of time and I want people to know that my nation, my people, here on the West Coast are going to do what it takes to stop this one pipeline."