Twice as many residents caught COVID-19 at Mississippi's for-profit nursing homes, and nearly three times more died there, an analysis of health data by the Mississippi Center for Investigative Reporting shows.

The average number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in these for-profit homes? Four in 10 residents.

One possible factor: 80% of Mississippi’s nursing homes had already been cited for infection-control problems before the pandemic hit.

Charlene Harrington, a professor emeritus at the University of California at San Francisco who discovered similar results in a just-released study of nursing homes in California, said the current pandemic is exposing problems that have persisted for decades. “We’ve just looked the other way for 30 years,” she said.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration has been investigating three nursing homes in Mississippi, all of them for-profit, for workplace catastrophes or fatalities, including Lakeside Health & Rehabilitation Center in Quitman. One of the home’s nursing assistants, Carole Faye Doby of Stonewall, died of COVID May 15, and two residents also died of the disease.

A week or more before she contracted the coronavirus, Doby warned her family that “things were getting bad at the nursing home, and that we didn’t need to come around,” recalled her daughter, Shenika Jackson of Clinton.

She said her mother shared that a fellow worker and a resident (who later died) had both come down with the disease.

On May 6, Doby was tested for COVID. Days later, they saw her on Mother’s Day, Jackson said. “We did see her on Sunday, Mother’s Day. We sat outside the porch and ate lunch. She was inside the window.”

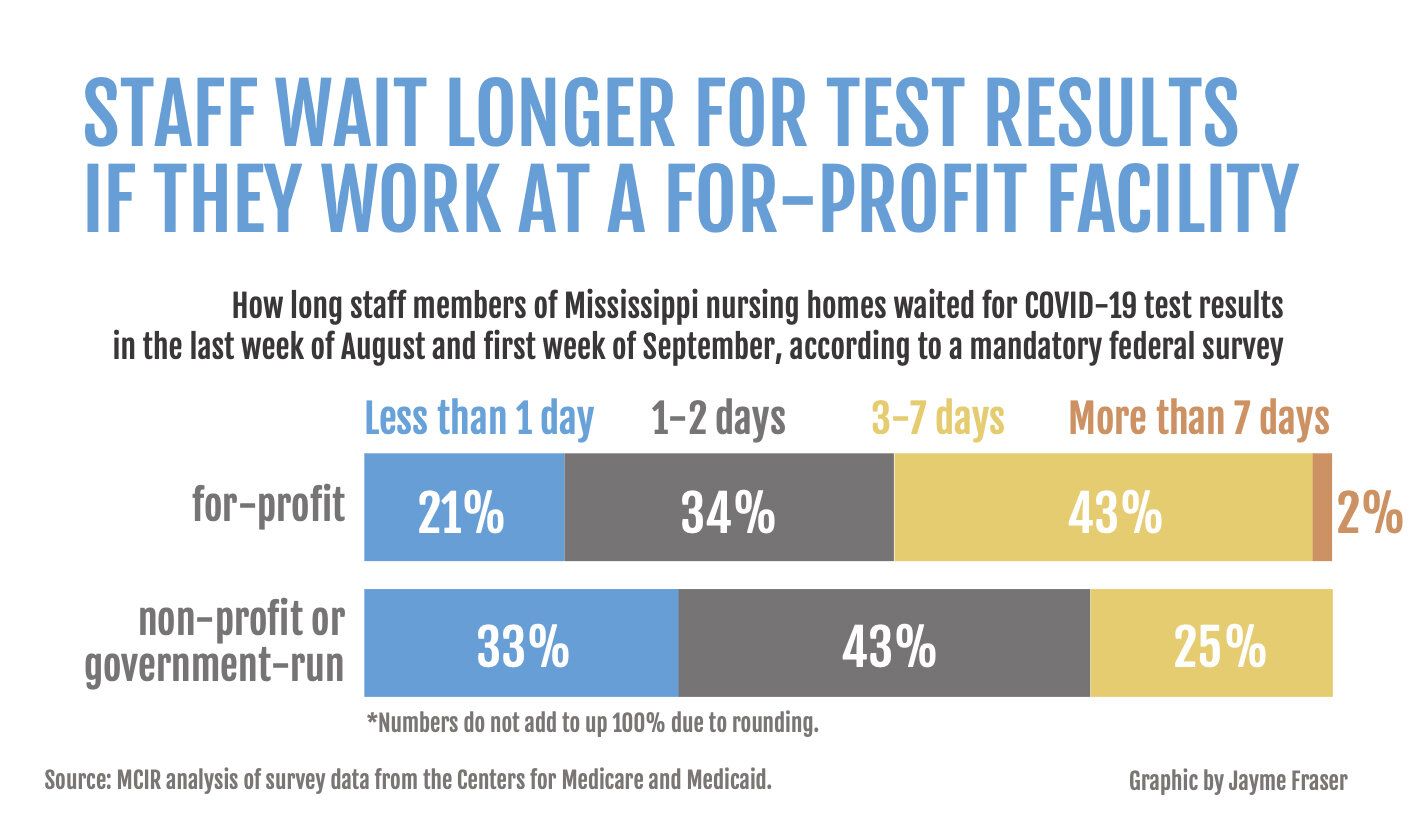

By May 11, her mother still didn’t have results and continued to get sicker so she saw a doctor, who had her rushed to the hospital by ambulance, Jackson said.

Because of COVID, she couldn’t visit with her family, except by way of video calls on her smartphone, Jackson said.

On May 15, four days after her mother entered the hospital, she was placed on a ventilator. Hours later, she died, less than a month after she had celebrated her 63rd birthday.

Jackson said the news stunned her and the rest of her family because her mother was “very healthy.”

From May through Sept. 13, federal data shows 94 COVID-19 cases that led to the deaths of 10 residents and one staff member.

Last month, Jackson said an investigator from OSHA contacted her and asked if her mother could have contracted the disease elsewhere.

Jackson replied no, saying the only places her mother went were work and home.

Since 2017, the 120-bed nursing home has been cited for seven deficiencies, and has also been fined $13,868. Medicare ranked the home “much below average.”

In 2019, a licensed practical nurse was caught using a device to measure blood sugar on different residents without disinfecting the device, risking the spread of blood-borne diseases and placing the resident in “immediate jeopardy,” according to the Medicare report.

Asked why she had not cleaned the glucometer, the nurse “shrugged her shoulders and stated she did not even think about doing it,” according to the report.

A Pensacola, Florida, company, Gulf Coast Health Care, owns Lakeside, seven other homes in Mississippi and 34 homes in Florida. One Mississippi home, Dixie White House Health and Rehabilitation Center in Pass Christian, saw 31 residents and 16 staff contract COVID, according to the latest federal data, despite having only 55 beds. Four residents died.

Most of these Mississippi homes have a poor record. Four have been fined a total of $67,567, including the 60-bed Singing River Health and Rehabilitation Center in Moss Point, which has seen 57 cases of COVID among residents and staff members as well as five deaths. In recent years, the home has suffered 25 deficiencies and has been fined $31,831.

Gulf Coast Health Care officials didn’t respond to repeated messages and questions left at their office.

Nursing Homes Ground Zero for Pandemic

Nursing homes have become ground zero for the pandemic in the U.S. with about 40% of the deaths, despite having only 7% of the cases.

Of the more than 200,000 deaths so far, more than 77,000 took place among residents and staff members at nursing homes.

“There is no excuse for having that many deaths,” said Harrington, who has studied nursing homes for decades. “Nursing homes are less than one-half of 1% of the population and yet they’re accounting for all these deaths.”

In Mississippi, these deaths have surpassed 1,200 residents (not counting at least 27 staff members, who all died from COVID-19 they contracted at for-profit homes since May).

Despite such grim numbers, most of the state’s homes aren’t testing asymptomatic staff and residents as part of a surveillance program because operators say they lack PPE, supplies, trained personnel, access to a laboratory or the like.

When COVID hit, policymakers and political leaders focused on keeping hospital patients safe, but neglected those inside nursing homes, Harrington said. “If these nursing homes had had the right staffing and had PPE and had enforcement of what nursing homes should be doing, we wouldn’t have had all these deaths.”

Federal officials say they have saved lives.

“The Trump Administration’s effort to protect the uniquely vulnerable residents of nursing homes from COVID-19 is nothing short of unprecedented,” Seema Verma, administrator for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, said in a statement made public.

CMS convened an independent coronavirus commission, which delivered its report this month.

Verma said these findings represent “a resounding vindication of our overall approach to date.”

The conclusion of the report?

The pandemic “has exposed and exacerbated” long-standing problems in nursing homes with many believing the nation’s “patchwork approach to infection prevention and control” has played a role in “our nation’s inability to contain the spread of the virus.”

OSHA Investigates Mississippi Nursing Homes

OSHA has also investigated Bedford Care Center of Hattiesburg for a catastrophe or workplace fatality. The facility has seen 43 COVID cases and the deaths of 13 residents and one staff member, according to federal data.

Since 2017, the 152-bed nursing home has been cited for 15 deficiencies and fined $6,500. Medicare concluded the home was “much below average,” detailing the escape of a resident because a receptionist was busy on her cell phone.

Bedford is owned by a limited liability corporation of the same name in Mississippi, according to the Mississippi Secretary of State. There are seven other Bedford Care Centers across the state.

Bedford Care Center did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

In June, OSHA began investigating Diversicare of Brookhaven for a catastrophe or workplace fatality. The nursing home has seen 60 cases and the deaths of 10 residents and one staff member, federal data shows.

Since 2017, the 58-bed nursing home has been cited for nine deficiencies that included aides failing to wash or sanitize hands or use gloves. Medicare graded the home “above average.”

Diversicare of Brookhaven is owned by a limited liability corporation named Diversicare Leasing Company in Brentwood, Tennessee, according to the Mississippi Secretary of State. Across Mississippi, there are 10 Diversicare nursing homes.

Diversicare did not respond to requests for comment.

In August, OSHA began investigating Starkville Manor Health Care and Rehabilitation Center, which Medicare has ranked “much below average.” Since 2017, the 119-bed nursing home has seen 83 COVID cases and the deaths of 11 residents and one staff member. The home has also been cited for 17 deficiencies and fined $13,627.

Starkville Manor is owned by the Centennial HealthCare Holding Company of Atlanta, according to the Mississippi Secretary of State.

Starkville Manor officials told MCIR they do not comment on investigations.

The company also owns The Oaks Rehabilitation and Healthcare Center in Meridian, which ranked “much below average” and was fined $22,874 for violations last year. Although the facility has only 82 beds, it saw 48 COVID cases as well as the deaths of 30 residents and three staff members.

For-Profit Homes Suffer From Worse Staffing

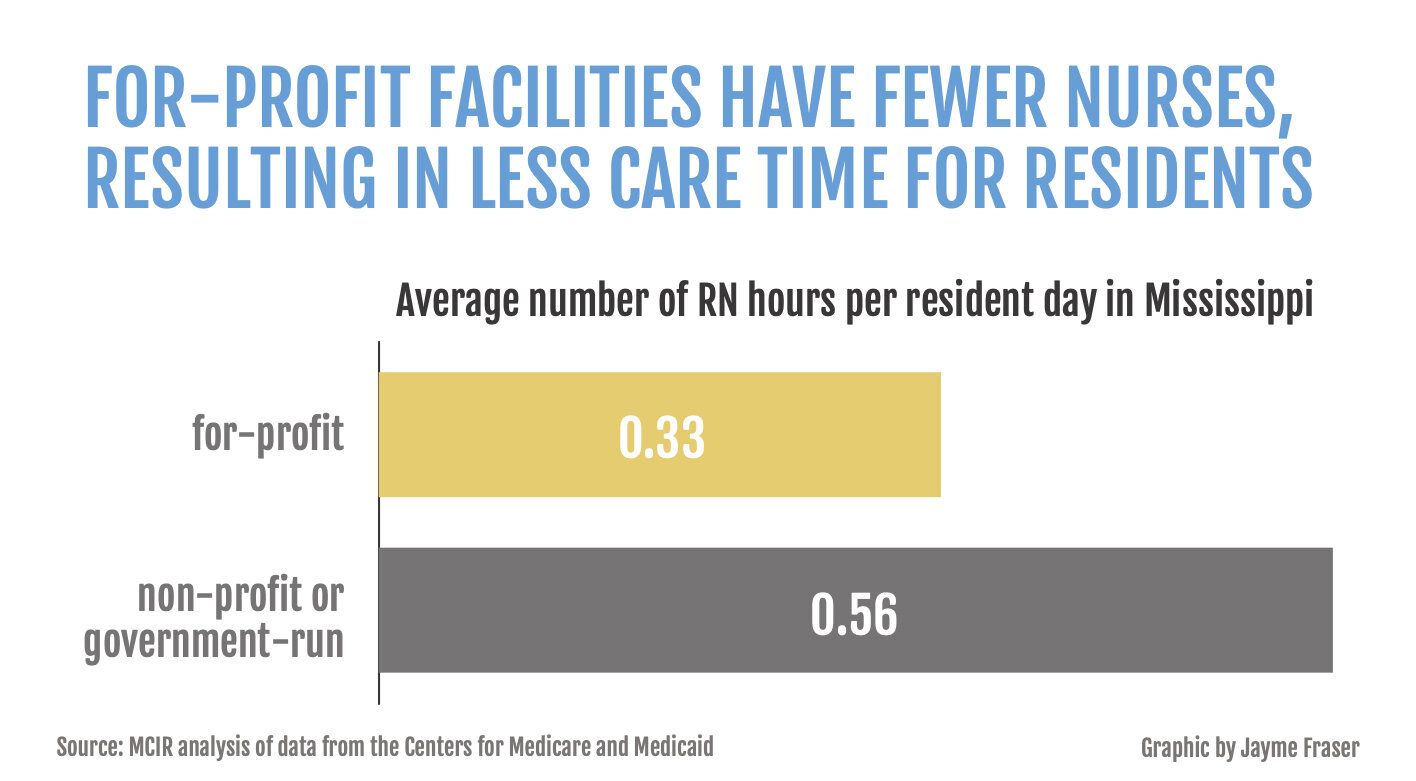

Staffing at for-profit nursing homes runs well below the levels of nonprofit or government homes.

Nationwide, for-profit facilities schedule registered nurses to work an average of 26 minutes per resident each day. That number is 40 minutes at nonprofit and government-run homes. That’s a difference of 34%.

In Mississippi, the level of care is lower, and the gap is even larger. For-profit facilities schedule registered nurses to work an average of 20 minutes per resident each day compared to 34 minutes at nonprofits, translating into a 41% difference.

Harrington said that lack of personnel hurts the quality of care. A new study shows that nursing homes with lower staffing levels are having higher numbers of COVID cases and deaths.

She said that nursing homes “have been allowed to get away with it because states don’t have adequate monitoring. States have been complicit in not insisting on higher staffing.”

Black Residents Dying at Higher Rates in Miss. Nursing Homes

MCIR’s analysis shows that Mississippi nursing homes with a higher percent of Black residents had higher rates of COVID cases and deaths.

When half or more of the residents are Black, the homes are seeing 55% more cases and 37% more deaths, compared to homes where Black residents accounted for less than 23% of the residents.

These results coincide with a just-released study on COVID in Connecticut nursing homes that shows “nursing homes with lower quality ratings and caring predominantly for Medicaid or racial and ethnic minority residents tend to have more confirmed cases in multivariable analyses.”

A previous study found that minorities tend to be cared for in facilities with limited clinical and financial resources, low nurse staffing levels, and a relatively high number of care deficiency citations, compared to White residents.

The death rate for majority-Black nursing homes was more than 20% higher than majority-White facilities, according to a Washington Post analysis of data from nearly three-fourths of the nation’s nursing homes. In homes that were 70% or more Black, that death rate was 40% higher.

Homes Become Haven for the Impoverished

Many nursing homes are poorly designed, packing up to four residents in a room, where they share one bathroom, Harrington said.

When COVID came, these homes failed to separate residents to keep them safe, she said. “Naturally, the staff got it, and so did the roommates.”

The pandemic has exposed the horrors of what’s happening inside these homes, she said. “Who wants to be put in a nursing home and get such terrible care?”

As a result, these homes have become the haven for the impoverished, “a place of default for people who are poor,” she said. “They don’t have families to take care of them.”

And those whose families wanted to visit their loved ones have been barred, resulting in many residents dying alone, she said. “It’s really been sad.”

COVID-19 Update: The connection between local and global issues–the Pulitzer Center's long standing mantra–has, sadly, never been more evident. We are uniquely positioned to serve the journalists, news media organizations, schools and universities we partner with by continuing to advance our core mission: enabling great journalism and education about underreported and systemic issues that resonate now–and continue to have relevance in times ahead. We believe that this is a moment for decisive action. Learn more about the steps we are taking.