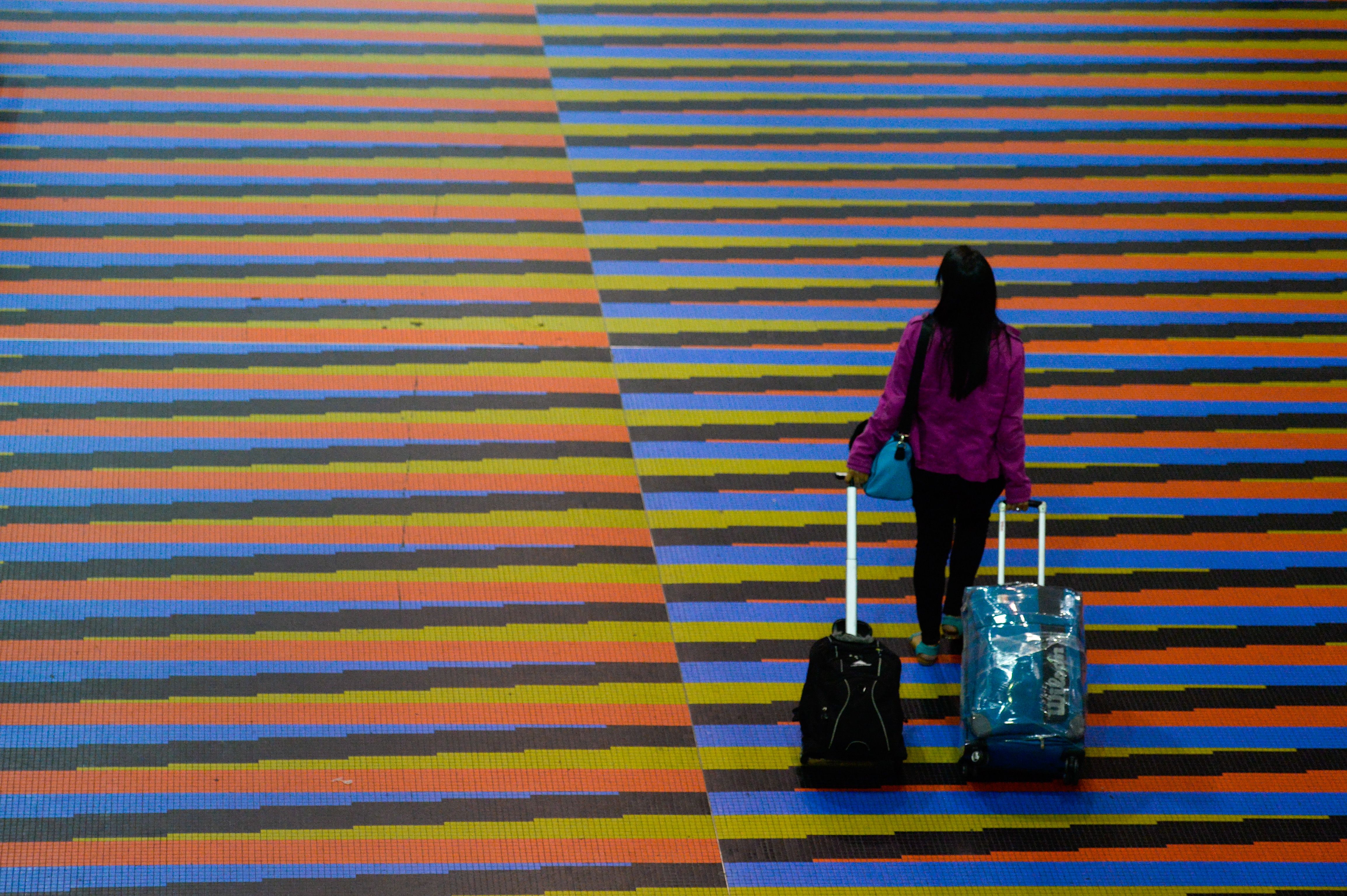

Neyla was unaware at the time, but she arrived in Venezuela to say goodbye. She barely made it into the country. Nicolás Maduro suspended all flights with Europe on March 12 because of covid-19. On March 11 she flew from Rotterdam, in the Netherlands, to Venezuela. As she exited the plane, a short woman in a hazmat suit pointed a thermometer to her forehead and a cameraman focused his television camera on her face, but her mind was busy elsewhere. Her mother had undergone an emergency operation.

Neyla landed at 10:00 in Puerto Ordaz, a city 400 miles south from Caracas, that served as headquarters to the biggest industries, hydropower plants and mining companies in the country. The largest airport in Bolivar state was empty. Javier, Neyla’s younger brother, picked her up. Driving past empty streets, the city seemed foreign. Abandoned alleys with decaying storefronts were like uneven burrows in a lonely desert. The country had changed, but she had changed even more.

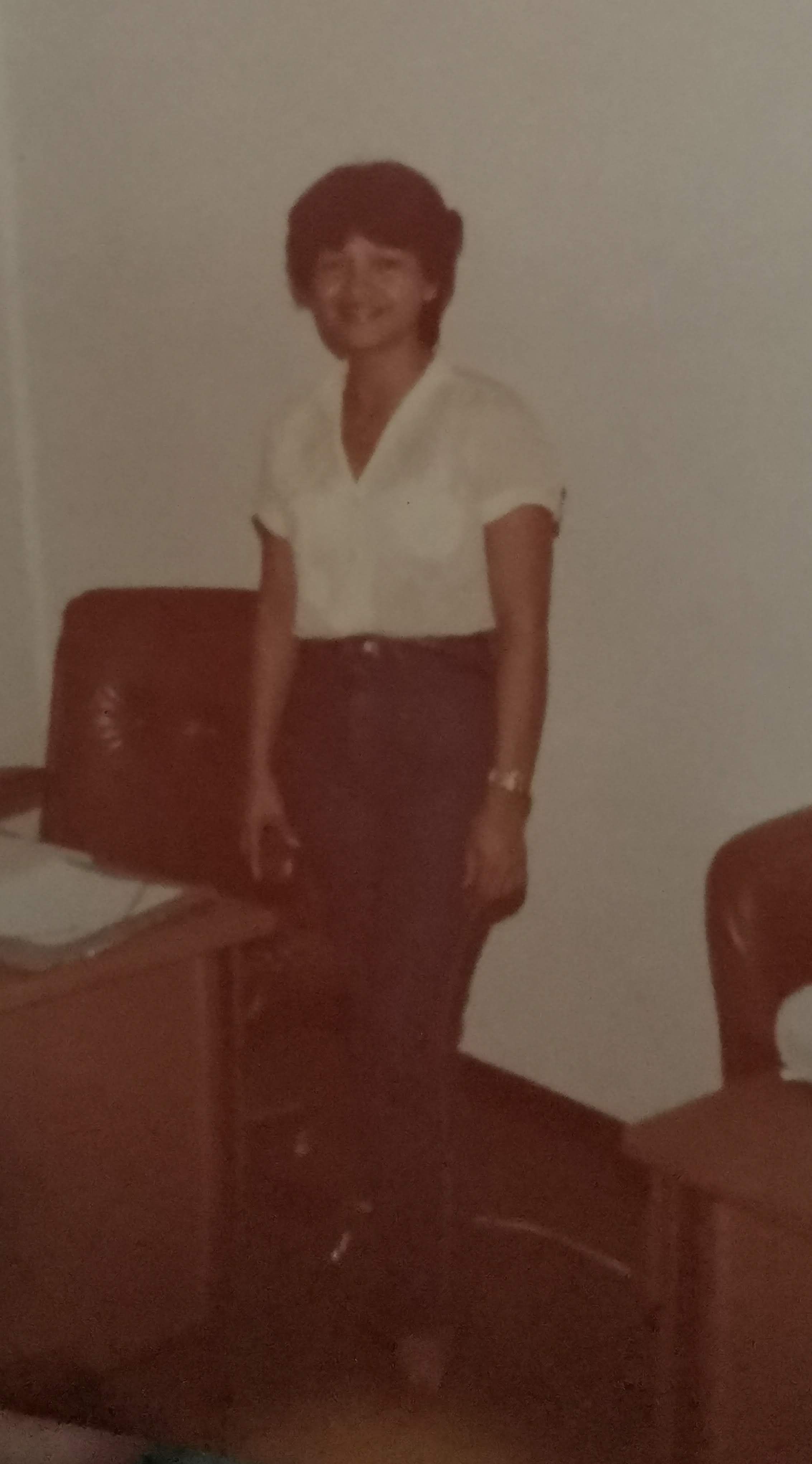

Neyla left Puerto Ordaz at 26 years old. She travelled to Canada for a six-month English course, but didn’t return. While in Toronto, her currency exchange request was denied. With dwindling savings, she quit school and found work. For months she cleaned hotels, student dorms and apartments. Then she found a better paying job in construction, bulldozing walls and moving debris. Seven months after her arrival, in July 2015, her brother sent a WhatsApp message that punched the air out of her lungs. “Dear siblings, Dad passed away last night.” Neyla read it again. And again. She looked for plane tickets, but she couldn’t afford any. Either way, she couldn’t make the funeral on time. Inside her small rented room, she wondered what her father would say. “Stay there, I’m already gone.”

Neyla packed her mourning with the rest of her belongings in two bags, and migrated to Ireland. She asked her mother, who lived in Venezuela, to send her father’s watch. In Dublin, that silver bracelet that set the tempo to her youth, became a token to hug as she wept. Without a funeral, it became his tombstone.

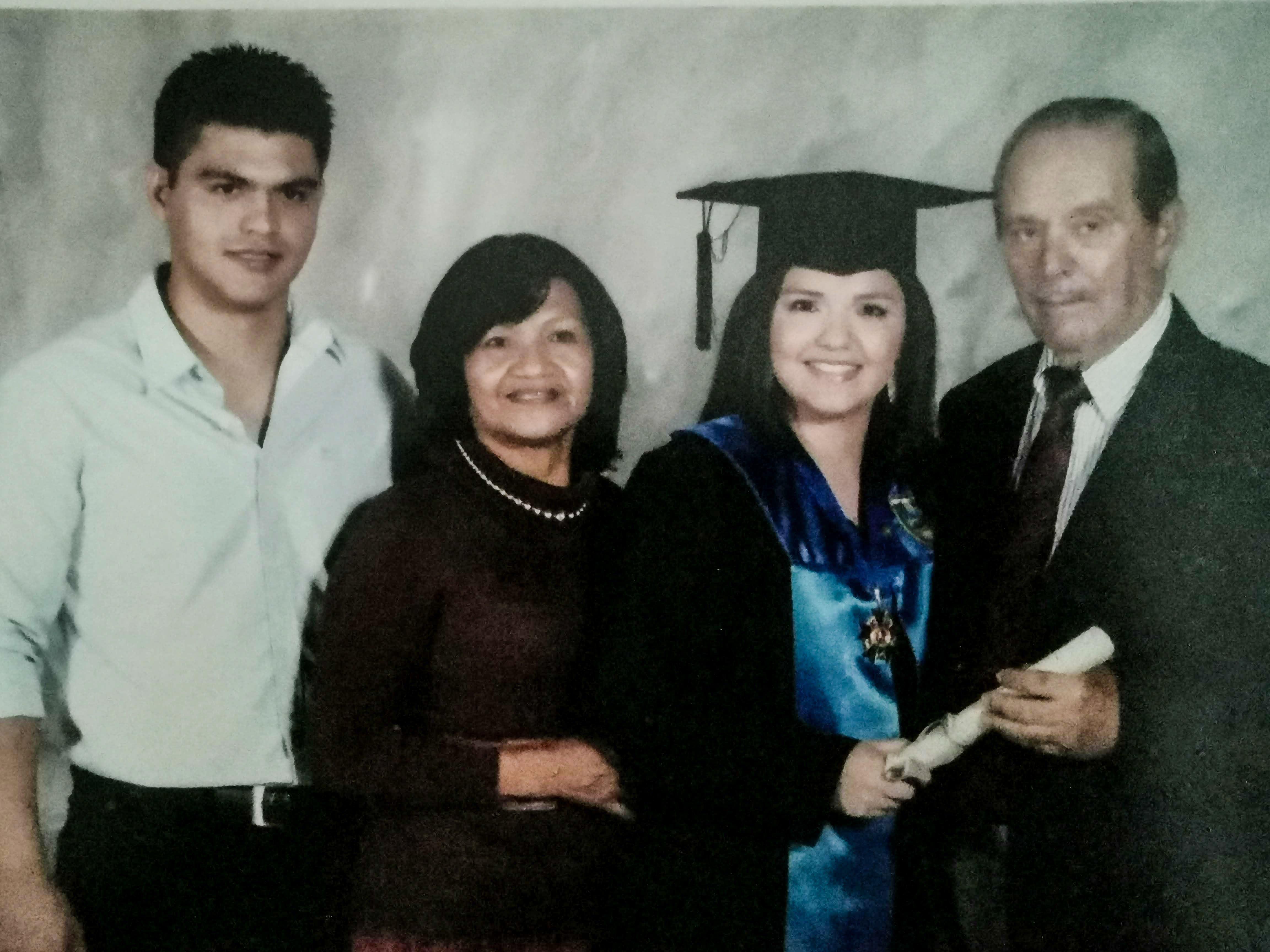

When Javier texted Neyla in March 2020 with news of their mother’s surgery, Neyla didn’t flinch. She refused another long-distance goodbye. She also wasn't going to leave her brother alone again. Their parents separated when she was 9 years old and both children grew up with Dad. Neyla had to reunite with her mother after many years apart.

On February 14, a month before the surgery, their mom developed a fever and had a hard time swallowing. She drank plant brews to alleviate symptoms because medicines were scarce and high prices barred her from buying off the counter. A few days later, her trachea collapsed on itself. Swallowing became harder. She couldn’t eat and lost weight. Javier drove her to 11 different doctors. In early March, an ultrasound revealed a calcification and a tumor in her neck. Days later, she had trouble breathing. The tumor grew from undetectable to asphyxiating in just three weeks.

In the house, Neyla left her baggage by the door and moved toward her mother’s room. She was wearing sunglasses, swinging on a rocking chair. Nightlights annoyed her. Neyla hadn’t seen her mother in six years, but she waved from a distance. No hugs or kisses. After sitting in three planes and walking through four airports, Neyla couldn’t put her mother at risk of contracting covid-19. They stared at each other in silence. Her mother couldn’t speak. “I’m here, Mom; rest, I’ll surely see you tomorrow,” Neyla told her. She nodded.

The diagnosis, advanced cancer stage 4, was terminal. It started in her thyroid and metastasized to her lungs. Javier hadn’t summoned the courage to tell Neyla.

The doctors opened an incision in her mother’s trachea, a tracheotomy, to facilitate breathing. Removing the tumor had compromised the muscles in her neck, so sputum accumulated in her throat and threatened to asphyxiate her several times a day. Neyla and Javier had to take her to the clinic for drainage. Only intensive care personnel were qualified to do it, the doctor said. But taking her to a clinic posed a covid-19 risk, so they hired a nurse for at-home care. Soon after, when a national gasoline shortage worsened, the doctor taught Neyla how to clean the tracheotomy herself. She had to slide a long tube down her mother’s mouth at a specific angle, and push it into her throat. She had to feel the tube to avoid it reaching the lungs. Taking too long would asphyxiate her; while inside, the tube blocks the airway. But moving too fast could scrape her trachea and provoke bleeding. And going in too deep could damage her lungs. It was a question of seconds and inches.

“I will go slow. If you want me to stop, I will,'' Neyla told her mother. When her mother shook, uncomfortable, Neyla thought she was killing her. Then they both got nervous and everything would get worse. Neyla never knew if she was doing it correctly. Regardless, she had to repeat the process several times a day.

The doctor recommended chemo. Your mother is strong enough to take it, she said. Javier was onboard but Neyla disagreed. Euthanasia, an action or omission that intentionally ends life to relieve pain or suffering, is legal and practiced in the Netherlands. Neyla was open to accept her mother’s diagnosis as irreversible. But Javier thought they had to do everything to keep her alive. Postponing the terminal diagnosis as much as possible. Ultimately Neyla accepted. After being far for long, she had to stand by him.

In Venezuela, chemotherapy medicine is only available through government dispensaries. But as with many other critical medicines, they were out. Through the private clinics, Javier and Neyla were able to contact a man that purchased medicines in Colombia and sold them in Venezuela. The first chemotherapy session was $250, but they feared gas scarcity would raise medicine prices, so they bought two sessions.

Neyla ran out of cash the first week. Savings in her Dutch bank account were exchanged to bolivares through a man in Spain. Neyla didn’t know him, but someone at the airport recommended him. Dollars were worth the same as euros. Without financial institutions to mediate currency exchange, people assign value to each currency depending on its use within the country. But Neyla didn’t mind the disadvantageous transaction. Dependability was worth more. When they needed bolivares in cash, they sold coffee. One of Javier’s clients had paid for a car part in coffee, he didn’t have any money, so they bartered.

Her mother started chemotherapy on Monday March 23, unaware of her own diagnosis. Javier and Neyla couldn’t tell her. They wanted to protect her. To mitigate covid-19 transmission risks, the family split up tasks. Neyla was in charge of patient care; she couldn’t be in contact with other people. Javier got food, medicines and medical supplies in his bicycle, because of the gasoline shortage. Their aunt prepared everyone’s food and a cousin served as Neyla’s substitute when she slept.

But Neyla didn’t sleep the first week. She constantly needed to check her mother’s breathing. She also kept placing cold wet cloths on her body. Chemotherapy took away her mother’s ability to self-regulate body temperature. Sleeping, she would sweat until soaking the bed.

As her mother regained strength, they held their first live conversation in six years. With a brittle voice, her mother shared some news: She had just finished a teaching course⏤she was going to teach law in her community. Neyla always feared her law practice. “I don’t want your signature to end up being used to forge documents, there is too much corruption everywhere.” At 64, she was too old to teach anyway, Neyla thought. She was naive like that: guarding dreams that would never come true. Venezuelan obstacles were insurmountable.

Neyla wanted her mother to open up to a life somewhere else, outside of Venezuela. But she refused. Neyla’s stories about her life in the Netherlands didn’t excite her mother. Even if Venezuela had taken away much, her mom still found ways to give to others and that fulfilled her. She never felt empty, she explained. She didn’t want to leave. She wanted to come home.

Eight days after the first chemotherapy session, her mother suffered a stroke. A clot blocked the blood supply to her brain, the doctor said. The following day, at home, her mom was calm. The nurse recommended moving her. Arms and legs were swollen and the skin was turning a yellowish color. Javier, Neyla and their cousin moved her from the chair to the bed. They started changing her diaper. Javier raised the legs as Neyla cleaned her, but before she was done, her mother’s body weight changed. Javier heard a long sigh, and then, silence. “Mom! Mom!” he screamed, shaking her shoulders, “wake up!” Neyla knew. She was watching her mother die.

Javier scooped her small body from the bed and ran to the car. Neyla held her mother’s body in the back seat as Javier sped through red lights towards the emergency room. Neyla knew her mother was dead, nothing could be done, but Javier didn’t. Both wore masks, half of their faces were hidden. So was the pain. Unable to find company in each other’s expressions, Javier stared at Neyla and didn’t let go. His mask, soaked in sorrow, grew heavy.

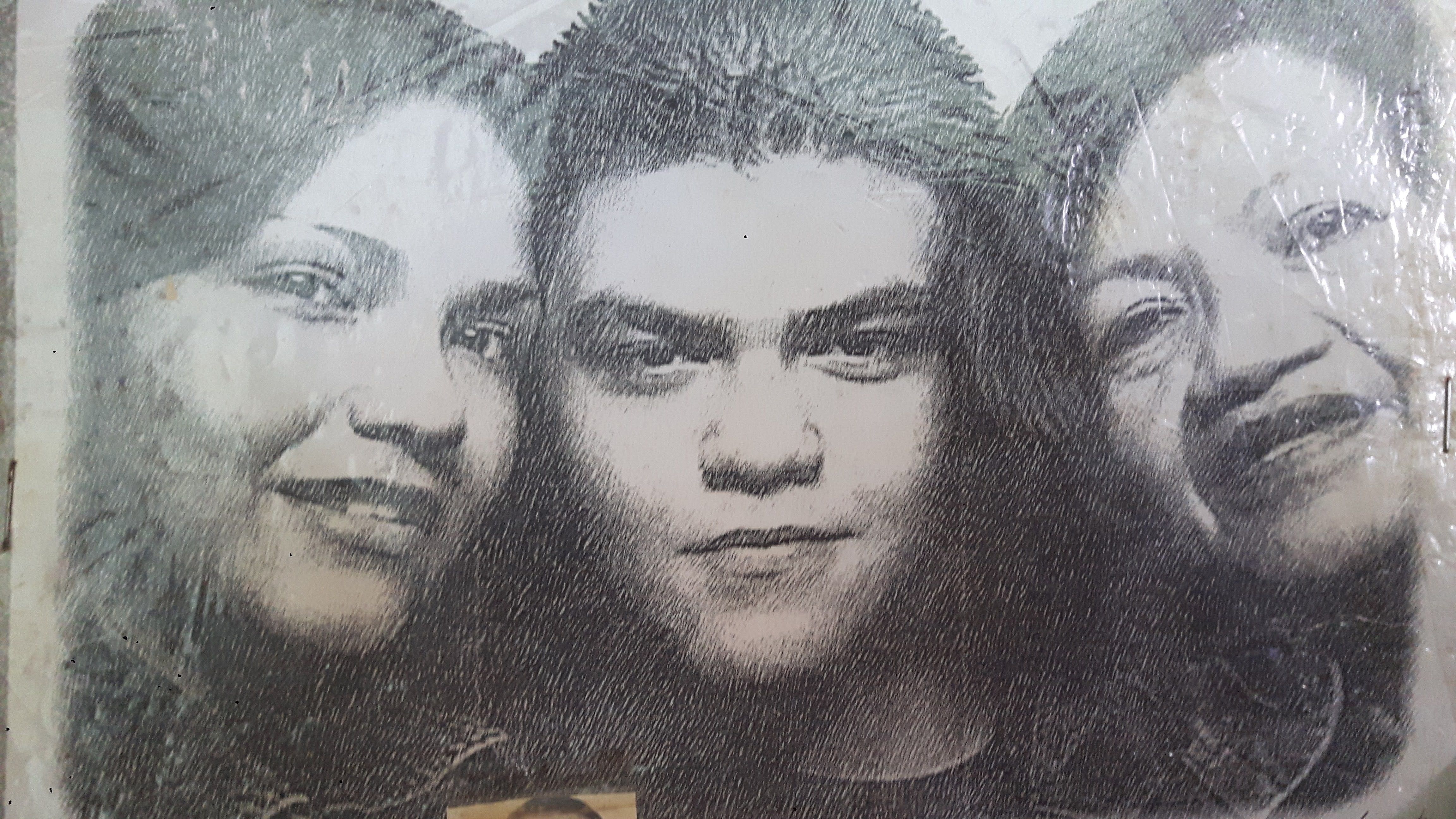

Their mother died on April 2, on their father’s birthday. And their dad died on July 13, 2015, on Javier’s birthday. Neyla’s family arrived into the world to leave together.

Ten people were allowed at the wake. In front of her mother’s coffin, Neyla wondered if the funeral home had enough gas to transport her body to the cemetery. She asked the driver. “We have little left but we’ve been working until noon because of the restrictions, so there’s enough,” he answered. Neyla felt privileged that her mother’s body only spent a day at the morgue. The funeral lasted 15 minutes. Their farewell, like everything else with her mother, was brief.

A Second Farewell

For Neyla, Venezuela was her parents. Without her affections, the space seemed like a distant memory of bygone times. Javier remained, but he had the age and energy to stay or leave the country. He could start over if he wanted to. Neyla looked for a path back to the Netherlands.

Every Friday she turned on the television awaiting news on airport closures. Air France had postponed her initial flight four times, the last one until September. To increase her chances, she wrote her name on the Spanish Consulate list for stranded nationals. Only three charter repatriation flights had departed in four months. It could be two months, six, or maybe a year, until the government opened airports, she thought. And her bank account was running dry.

Two days after their mother passed, Javier lost all his savings. A man contacted him, wanting to buy a car engine listed online for $400 in MercadoLibre. He sent a check for $9,000 “by mistake” and asked Javier to transfer back $8,600, subtracting the $400 purchase from the $9,000 check. Javier didn’t have a foreign bank account so he borrowed his best friend’s father’s account. His friend called, unsettled, his father’s account was overdrawn. The supposed buyer withdrew the $9,000 check before the bank could cash it. It’s a common scam, his friend explained. “God doesn’t love me,” Javier told Neyla, “he can’t send so much in such little time. He knows I can’t handle it all.” His friend’s father asked Javier for help to take the account to a positive balance. The man owed the bank $4,000. Neyla transferred some savings. “Can it be more?” Javier asked. “How do we eat then?” she replied.

Neyla, Javier and their aunt lived on $30 a week. A $1.40 per person per day. They calculated the bare minimum to stretch Neyla’s savings; it was the only money left. Every week they bought two whole chickens, and used what remained on vegetables.

Neyla lost the hard-earned luxury of making decisions for herself. She lost all control over her life. Her boyfriend awaited in the Netherlands but she had no way to get there. Her savings weren’t enough to feed herself indefinitely. She had no job and couldn’t get one. And she couldn’t sleep, awakening in the middle of night to check her mother’s breathing.

Neyla and Javier visited the cemetery on Mother’s Day. Javier searched the peripheries for her grave but didn’t remember the exact location. Neyla searched the middle of the grounds. They followed the engraved numbering until they found an uncle that rested in the same parcel as their mother, but her cement block was gone. From a corner, Javier shouted. The gray block was among strangers. Neyla took out a paint brush and canned paint she had bought as a teenager but scarcely used, and painted her mother’s grave. Since she was little, Neyla wanted to paint something important. In cursive handwriting, she traced her mother’s name. Out of the cement block she made a tombstone.

As covid-19 cases soared, two months passed and there was no news on resuming international air traffic. Neyla received an email from the Spanish Consulate in Venezuela on Monday June 22. A new charter repatriation flight was programmed for July 4, and she was in the passenger list. The ticket was $850. She didn’t have enough money, but immediately answered back with her details and contacted friends from Canada, Ireland and the Netherlands to borrow enough for the flight.

She spoke to another passenger from Bolivar to coordinate transport to the airport, 423 miles away. You’ll need a covid-19 test to board the flight, the passenger said, but they are hard to find. Neyla called the travel agency in charge of ticketing. They debunked the information. Regardless, Neyla and Javier decided to get one. The following day, Wednesday July 1, they saw the sunrise while queuing outside Los Olivos Centro de Diagnóstico Integral (CDI). The center didn’t open, so they drove to Uyapar Hospital, one of the most important public health centers in Puerto Ordaz. There were no covid-19 tests. After asking around, they heard the Castillito CDI had tests. They arrived before 8 in the morning and there was a queue. A few minutes later, a uniformed miliciana, part of a civil component of the National Armed Forces started by Hugo Chavez, said they had no tests. But the center’s doctor arrived at 9, and said they only had eight. “There aren’t enough for everyone, only for people with grave symptoms, so decide among yourselves who gets them,” the miliciana told the crowd.

People argued and shoved each other. A man approached the miliciana, his elderly mother had difficulty breathing. He took her to several hospitals but none admitted her. They requested a covid-19 positive test, he explained. The miliciana dismissed him, so he walked over to his car, took out a brittle old lady and seated her a few meters from the queue. With every gasp, the lady arched her back and shrank in pain. Breathing required every ounce of her strength. The miliciana allowed the lady into the doctor’s office for a test.

Neyla was the sixth patient. “People with grave symptoms need a test and you are asking for one to board a flight?” argued the doctor, annoyed. Neyla wanted to rebuke her but, suddenly, she questioned herself: Is my case really important? Do I deserve a test? She thought about her life in the Netherlands and summoned strength. “If I don’t get one, they won’t allow me to board the flight and return home.” The doctor handed a small square of paper with a seal on it; it was the test order.

At the medical lab, a young nurse sank a needle into Neyla’s arm without mediation. “I’m exhausted, I want these tests to run out,” he told another nurse standing nearby, without making eye contact with Neyla. Next to the young man, there were two open boxes filled with covid-19 rapid tests. As the World Health Organization recommends against using rapid tests to diagnose covid-19, 94% of testing in Venezuela until July was done using these tests. As Neyla awaited the results she thought she recognized the young nurse from somewhere. Soon she realized it wasn’t him; it was his exhaustion that seemed familiar.

For days, Neyla awaited a phone call from the military command at the Bolivar Integral Defense Zone (ZODI). They would provide a safe-passage authorization to drive from Puerto Ordaz to the airport, wrote the consulate. Only the Armed Forces could authorize her. Since May 13, a government-issued State of Alarm Decree restricted free passage throughout the country. The flight departed in three days and there was no contact.

Neyla drove to the ZODI office, inside the Puerto Ordaz airport. “We know nothing about that flight, you have to bring all the paperwork like everybody else,” said the highest-ranking military in the office. “Include every supporting document you can because the commander has to approve your request,” said Martinez, a second military present. It was noon and all printing and copying centers were closed because of quarantine. But the military told her the process took two days. If she wasn’t able to provide the paperwork that day, she wouldn’t make the flight. Neyla and Javier drove across town to another brother’s house. He had a printer. Neyla assembled a folder with her plane ticket, covid-19 rapid test results, consulate email, copies of her Spanish and Venezuelan passports and a letter explaining her travels, and handed it to the military men.

On Thursday morning she packed a few books and family photographs into a suitcase; it was all she had left in Puerto Ordaz. At 10 a.m. she headed to the ZODI office. Martinez looked for her authorization in a pile of documents. He couldn’t find it. He searched in another pile. “You are first in the rejected pile,” he said. There was a note on the backside of the document: “Speak to the commander,” it read.

Close to noon the high-ranking official took Neyla to the commander’s office, in front of the tarmac. “He’s in a meeting; wait here,” the official said. Soon after, a military jet landed and uniformed paramedics entered the terminal. It was a military ambulance, they told her. Later, an ambulance arrived and a patient was transported on a gurney from the car into the tarmac and onto the plane. Neyla remembered this time in the Netherlands; she saw a helicopter pick up a neighbor and transport him to a nearby hospital. No one would pick her up in Venezuela, she thought.

Neyla got tired of waiting and impulsively opened the commander’s door. The high-ranking official was sitting in a chair playing with his phone. “It’s good you are here. By the way, the commander told me to speak to you,” he said. The authorization was approved but he had to write down the document so the commander could sign it. “Come back at 3 p.m.,” he said.

At 3, the document was not ready. The official wanted to accumulate several forms so he could reduce the number of trips to the commander’s office for his signature. Neyla had to leave for Caracas that day, but driving at night was too dangerous. She sat near Martinez and the other official to pressure them into fast-tracking the process. “What motivates you to work?” she asked them, and immediately, feared being rash. “Nothing, but we are not like you civilians that get tired, give up and leave. We have to stick it out,” Martinez said.

At 3.30 p.m., an elderly man entered the office. He had a surgery scheduled in Paris and needed authorization to reach the airport. But there were no commercial flights. Neyla understood they were on the same flight. So did the officials. The high-ranking military man grabbed both authorizations and walked to the commander’s office. Minutes later he handed them out, signed.

Neyla and Javier left Puerto Ordaz at 4, but it turned dark and they decided to sleep in Anaco, in Anzoategui state, a city with just over 140,000 inhabitants. They were running low on gas and needed to refill the tank to reach Caracas. They searched for gas stations in the city. Only one was open, and a long queue followed. Several men played dominoes and drank beer on a plastic table near the pump. They had been queueing for five days.

Javier left his car in a friend’s house and found a cab willing to take them to Caracas. The taxi driver had to pick up his stranded wife in the capital but lacked authorization to travel. Javier and Neyla had what he needed to get there. They agreed on a $160 fee and drove off on Friday morning. In the first military checkpoint, still in Anzoategui, a military official signaled them to stop. He asked for the authorization. Neyla argued her case: She was boarding a repatriation flight. After speaking, as she stared at the uniformed men, she wondered if giving out that information was counterproductive. If they know she’s travelling, maybe they think she had money. “Well, boss, how are we going to save him?” the official asked Javier, referring to the taxi driver. His name was not on the authorization. The driver handed the official $10 out of Neyla and Javier’s payment and the military let him through. They passed eight military roadblocks on their way to Caracas. Militarymen stopped them in five, and asked for bribes in three.

They arrived at a relative’s house at 4 in the afternoon, left their baggage and searched for jeans at a nearby market. Pants were too expensive in Puerto Ordaz and Javier needed a new pair. When they got back to the building there was a power outage in the neighborhood. They had to climb 17 stories to reach the apartment. As they walked past the eighth floor, the light came back on. Javier and Neyla wanted to shower, but there was water rationing in the city. They had two options: Use the water tank and bathe with a bucket, or wait for the running water to come at 8, and shower for a brief moment. Water ran once a day and for only 10 minutes at times. They waited.

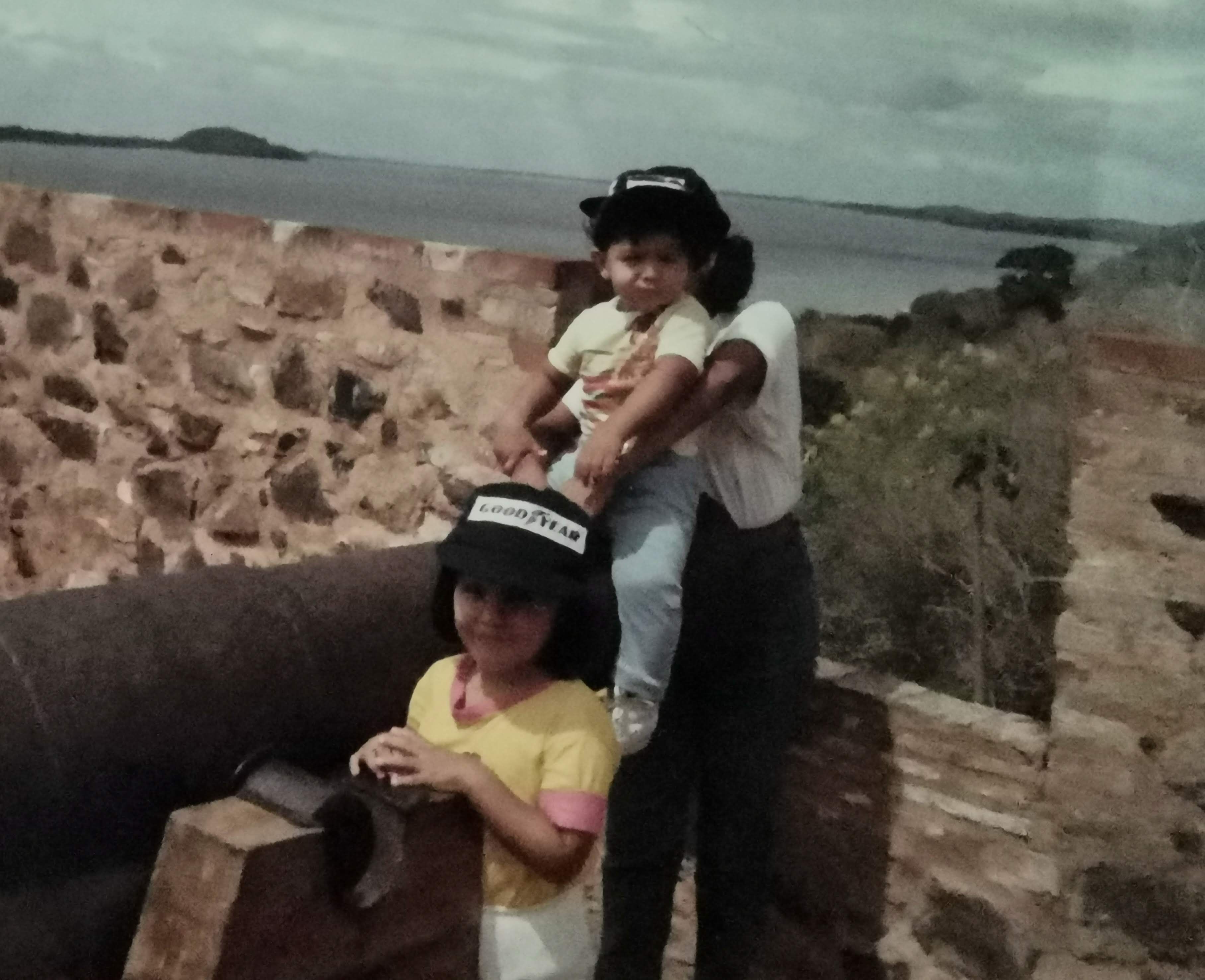

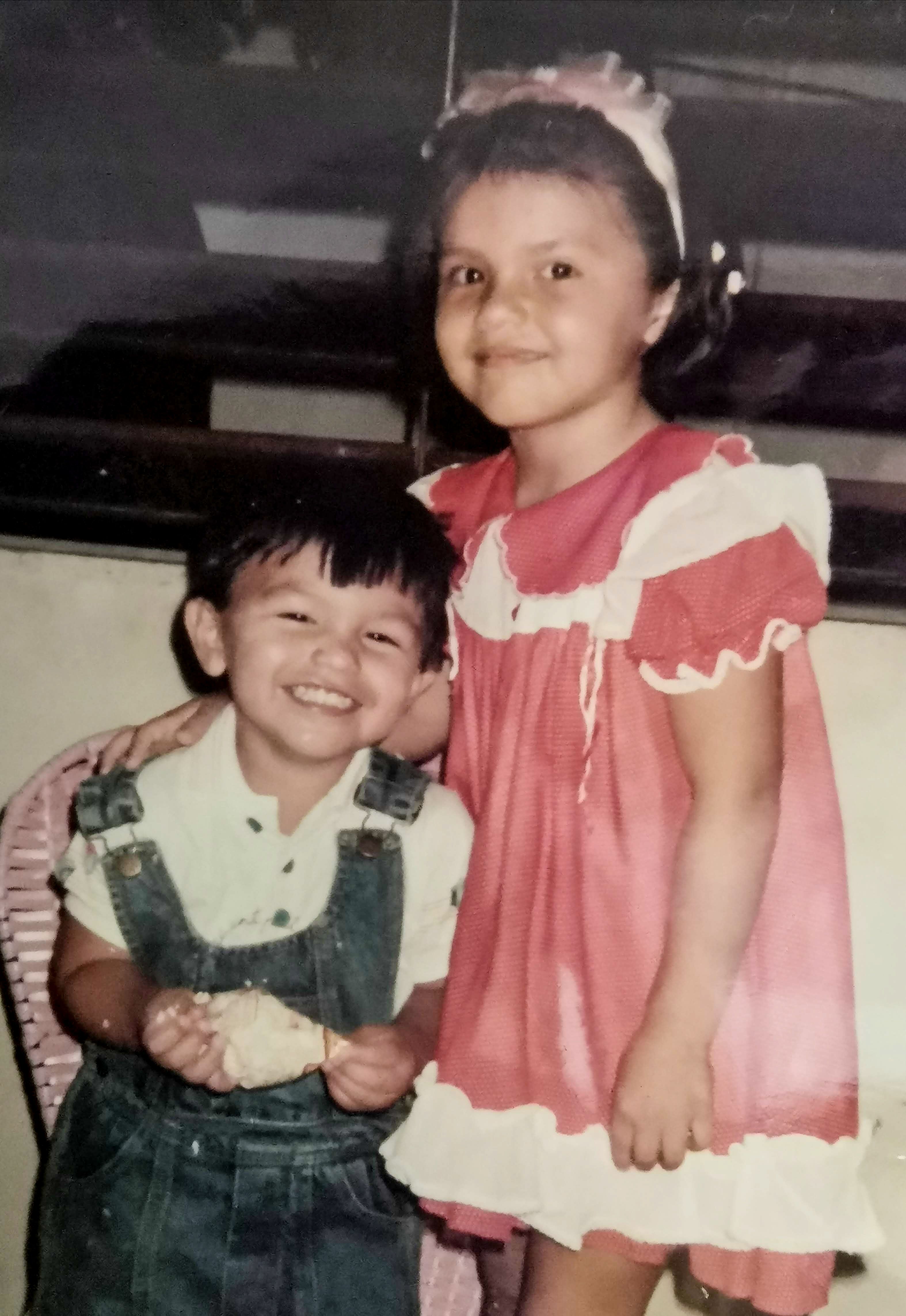

Laying on a floor mattress, Neyla and Javier spoke well into the night. “You have less than 24 hours left,” Javier whispered. They exchanged childhood memories and shared updates on their lives, now separated by an ocean. The last time they had seen each other, they were children. Neyla thought about Javier’s life in Venezuela. She couldn’t protect him from a distance. Neither could their parents, both were gone. They only had each other.

On Saturday July 4, a military official and friend of the family offered to drive Neyla and Javier to the Simon Bolívar International Airport. He needed money to complement his meager salary and took any job available. As they drove toward the coast, Neyla asked Javier to swear to never make her come back to Venezuela. They said goodbye at the airport entrance.

After queuing for four hours, Neyla reached the first airport counter. She handed her Spanish and Venezuelan passports to the Spanish Consulate official. The man opened the documents and searched for Neyla’s name in a list. Then in another list. “Did you notify the embassy that your Venezuelan passport expired? You are not on the authorized list.” Neyla sank. Something crumbled inside. No. Passport offices were closed during the pandemic; she tried renewing it without success. “It will be up to the Venezuelan authorities to let you board.”

Three armed military officials stood between the first and second counters. “Passport, please,” ordered the tallest one. Neyla handed it over and lowered her head. She didn’t want to call any attention to herself. “How long have you been overseas?” he asked. “Six years.” Neyla focused on the man’s worn-out black leather boots. “Go ahead,” he said.

The flight was scheduled to leave at 5, but there were delays. If she missed her connecting flight between Madrid and Rotterdam, she didn’t have enough money to buy a new one.

With the flight ticket at hand, she joined the immigration queue. She imagined all the different ways to explain her situation. And also, all the ways in which they could deny her exit. She thought of convincing answers for each possible argument. Neyla was so nervous she failed to notice the immigration officer seal her passport.

Inside the terminal, she sat on the floor in front of the gate. Two hours passed and there was no update on the flight delay. The travel agency had no information. Neither did the airline. Four Military Counterintelligence General Direction (DGCIM) uniformed officers stood near the gate. Nine Bolivarian National Guards joined them. The 13 officials waited. At 8, a passenger Neyla met at the queue showed her a phone screen. It was a tweet. Maduro didn’t authorize the flight, it was cancelled, it read. But nothing was happening in the gate, Neyla thought. If it were true, something would.

Minutes later, at around 8:45, the flight crew navigated the uniformed officials’ barricade and entered the gate. At 9, airline personnel called on passengers to board. Neyla postponed her excitement. In the previous repatriation flight, passengers boarded, and later, Venezuelan authorities ordered people off the plane. They delayed departure for hours without explanation.

An hour passed. Neyla was too tired to feel worried. Instead, she felt resigned to whatever happened next. At 10:40, the pilot spoke: “Welcome. We apologize for the delay but Venezuelan authorities refused to let us take off. Everything is in order now. We can depart.”

The flight left Maiquetía with a six-hour delay. Through the window, Neyla saw the Caribbean merge with the coast. Blinking lights from the mountain slums blended with the stars. As she got further away, the familiar silhouette disappeared into the darkness. Soon, she was motherless.

To read this story in Spanish, click here.